Georgian horsemen in the Wild West show – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2019

Georgian horsemen in the Wild West show

By Irakli Makharadze

Translated from Georgian by Salome and Nino Makharadze

In 1905, American journalist and author Ernest Poole and his Russian guide traveled the Russian Empire’s South Caucasus, Georgia (now the Republic of Georgia) and visited the western part of Georgia—Kutaisi, Batumi, and Guria. (Compared to the other parts of the country, Guria is relatively young, being first mentioned in the annals of the eighth century AD. Gurians are ethnic Georgians who speak a local dialect of the Georgian language). In one Gurian village, the pair bumped into a “sad-eyed” peasant who spoke fluent English.

“Where in hell did you learn English?” Poole asked.

“Four years with Buffalo Bill,” the peasant replied. “He made me a Cossack in the Rough Rider troop, and we had one hell of a good time. But I broke my leg bad. So here I am at home…”

Although the identity of this rider has not been confirmed, it’s possible he was Bathlome Baramidze, a member of Buffalo Bill Cody’s famous “Congress of Rough Riders of the World”—who broke his leg in 1902.

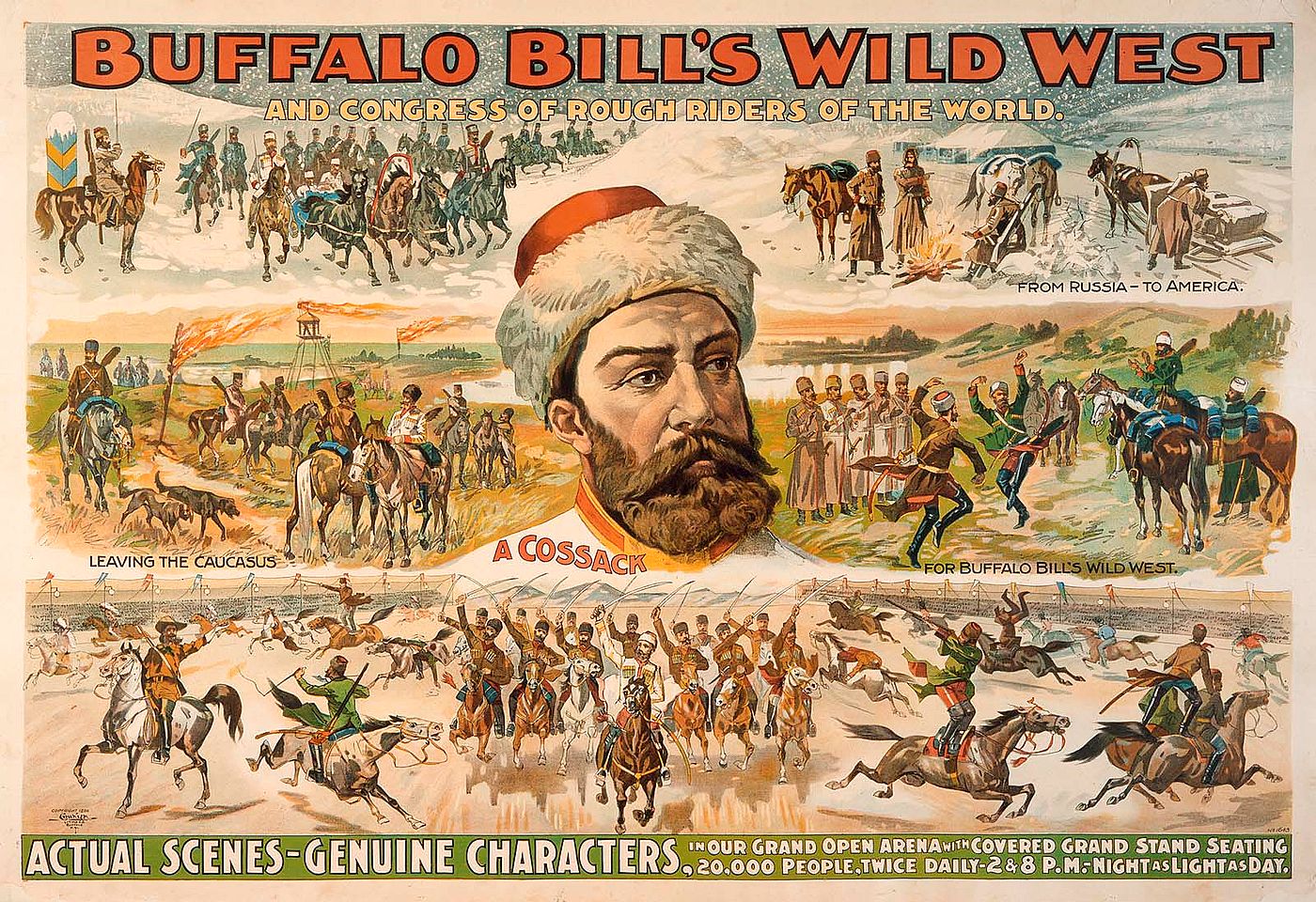

Georgians or Cossacks?

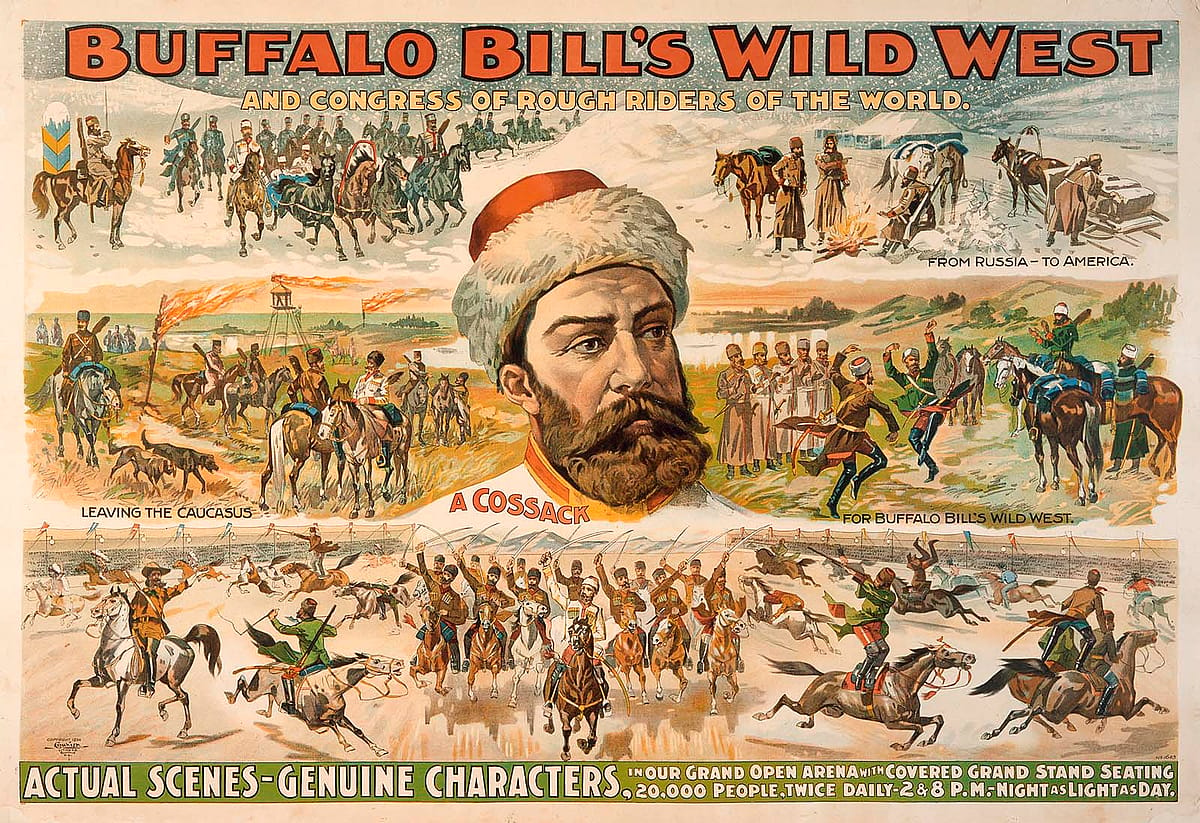

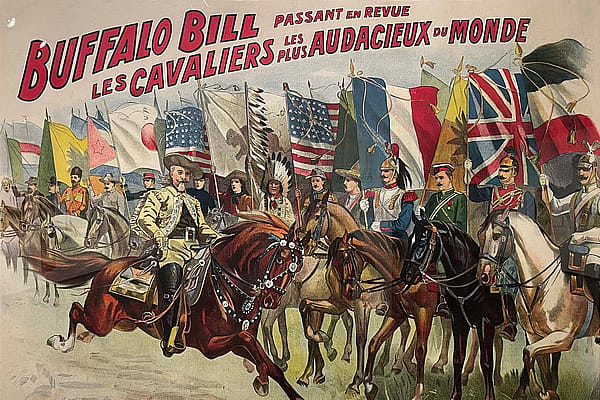

The history of the Georgian-Gurian riders began in 1892, when they first joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in England. For more than thirty years, they performed as the Russian Cossacks in the Wild West, as well as other shows and circuses. The Gurian riders were called Cossacks for different reasons, but perhaps the most important was the fact that Georgia was part of the Russian Empire at that time (Georgia was annexed by Czarist Russia in 1801 and by Soviet Russia in 1921.), and so each Georgian was considered Russian.

Regarding this confusion, it might be worth mentioning that the group’s employers were the ones responsible for creating this initial mystery in the media of the day. They declared that the riders came from the southern part of the Russian Caucasus, the mountains where the Cossack family in Lord Byron’s Mazepa were located. Even the riders boasted that they were awarded medals for bravery, but it was a con, of course. Other newspapers, like the Hutchinson Leader of Hutchinson, Minnesota, went even further, reporting on July 24, 1908, that “The Cossacks were the real thing, right from the Czar’s army. Splendid horsemen and brave fighters, they are also fierce and cruel. They were members of the same regiment that charged upon a throng of men, women, and children in the streets of St. Petersburg two years ago and shot, sabered, and murdered a thousand.” No wonder such stories helped make them popular figures.

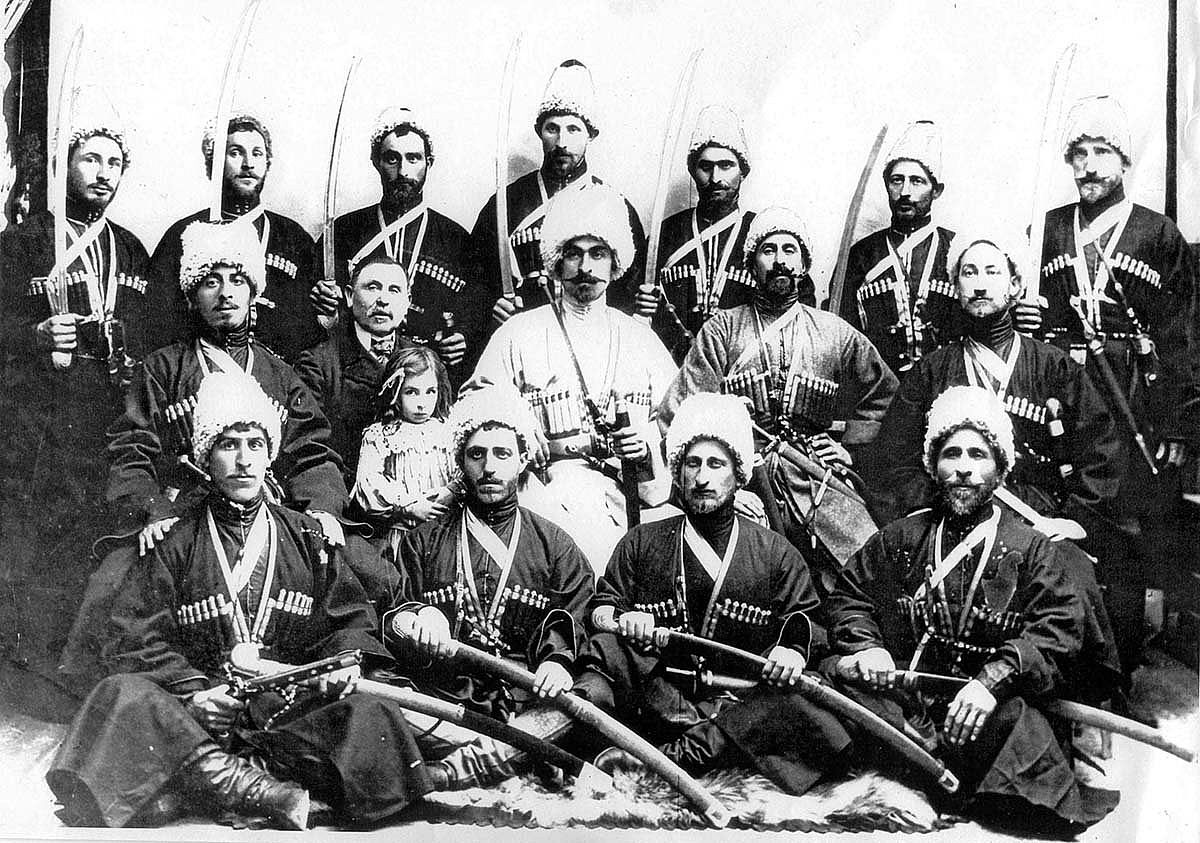

Of all the tales told about the riders, though, the one most often repeated is the story of their recruitment. One Thomas Oliver arrived in Georgia to locate riders for the show in the United States. (Later, Oliver interpreted for the Georgian riders in 1892 – 1896, presumably in Russian or quite possibly, in Georgian. Riders called him “Tommy.”) At the Black Sea port of Batumi, Oliver stopped at the home of James Chambers, the British Council. An employee of Chambers—a fellow named Kirile Jorbenadze, who was on familiar terms with some of the riders in Guria—offered help. Oliver accepted, and soon the two men, plus vice-council Harry Briggs, departed to the village of Lanchkhuti. On the way, they stopped at the village of Bakhvi where they visited Ivane Makharadze, a distinguished rider who promised Oliver that he would be responsible for signing up other riders.

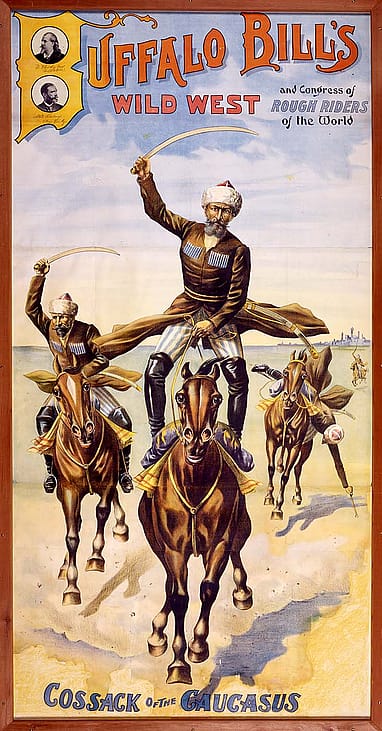

It wasn’t long before a group of ten riders underwent a special training, sewed six pairs each of the national dress “chokha” in different colors, and moved to Great Britain via France. Their chokhas were orange, yellow, green, and motley purple, colors that Georgian men occasionally used in their dress. Apparently, it was part of the spectacle to catch audience attention.

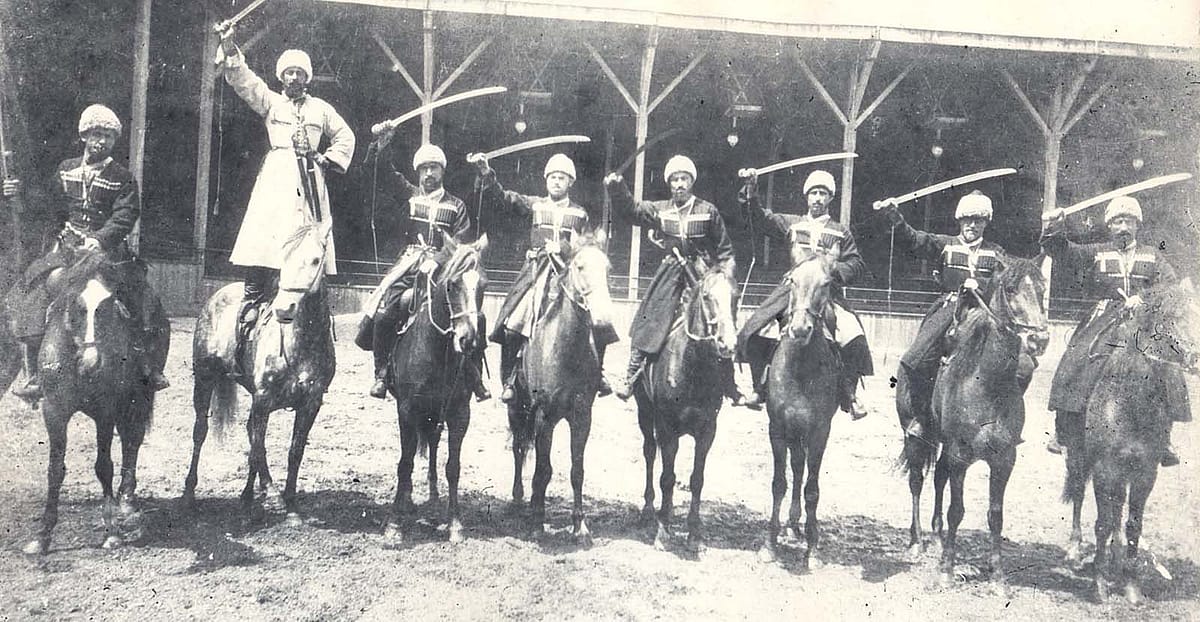

The first group of riders caused great excitement in London: The Georgians’ daggers, swords, and especially their eye-catching chokhas—decorated with pockets for cartridges—were a special topic of conversation. Aficionados said they resembled miniature sticks of dynamite.

On June 25, 1892, “Prince” Ivane Makharadze led the Georgians who performed in Windsor in front of Queen Victoria, the royal family, and other members of the aristocracy. Group leaders were mostly referred to in the programs as “Prince.” In fact, only some of the riders were of noble origin; the rest were mostly peasants from the surrounding Gurian towns of Ozurgeti and Lanchkhuti. Apparently, it was a publicity stunt to attract more people. At one point in the performance, when the Cossacks were doing their horseback work, Prince Henry of Battenberg (husband to the Queen’s youngest daughter), who was standing in the rear of the pavilion, said to the Queen in German, “Mamma, do you think they are really Cossack?”

Before the Queen had time to reply, Wild West show manager, Nate Salsbury, answered, “I beg to assure you, sir, that everything and everybody you see in the entertainment are exactly what we represent it or them to be.”

“It is probable that audience members were satisfied that the performers were Russians, and that they could present a colorful and exciting part of the show,” wrote historian Sarah J. Blackstone in her 1986 book, Buckskins, Bullets, and Business: a History of Buffalo Bill’s Wild WestM. Audiences wanted to see different kinds of presenters, and clever businessman Buffalo Bill Cody decided to involve representatives of other nations in his show. Georgian peasants became Cossacks; Sioux Indians became Cheyennes or Apaches; all Native Americans were chiefs; all Asiatic women were princesses; all army horsemen were colonels, and so on.

Off to America

In 1893, the Gurians traveled to the United States where they joined the Wild West show at the World’s Columbian Exposition or Chicago’s World Fair. “When the Cossacks came to the United States for the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893, the Americans picked up some hints and bright ideas,” penned Frank Dean in his 1975 The Complete Book of Trick and Fancy Riding. “From that date on, trick riding had a boom from coast to coast.” It must be noted that many visitors who came to see the fair attended Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show and then left, more than satisfied. Apparently, they thought the Wild West was the Fair!

Georgians won widespread recognition and significantly influenced cowboys. According to the noted western historian Dee Brown, “Trick riding came to rodeo by way of a troupe of Cossack daredevils imported by the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch [in Oklahoma]. Intrigued by the Cossack stunts on their galloping horses, western cowboys soon introduced variations to American rodeo. Colorful costumes seem to have become a necessary part of trick riding, and it is quite possible that the outlandish western garb which has invaded the rodeo area can be blamed directly on Cossacks and trick riders.”

The owners of circuses and shows had found a real gold mine—cheap artists, who were so popular that lots of people came just to see their performances. It is very interesting that the Cossacks became an essential feature of every respectable show of that time. Out of all the international performers, the Georgian riders’ performance was perhaps the most popular feature of the Wild West show; only Indians and cowboys enjoyed similar popularity. Here are two quotes from American newspapers:

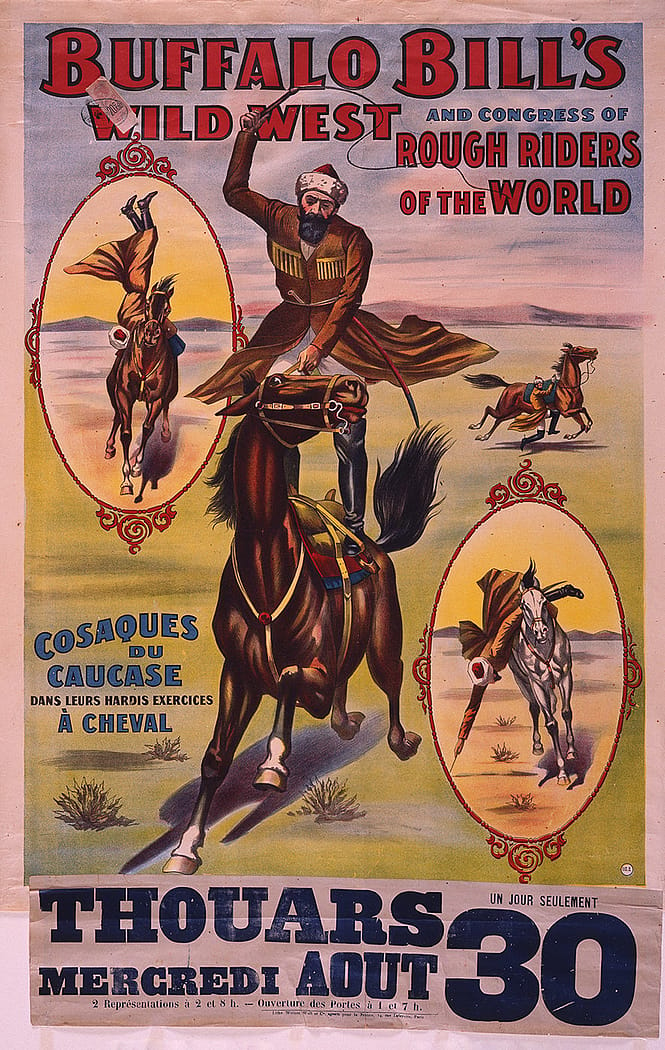

- “The strangely garbed Cossacks from the far-off Caucasus mountains, the most expert riders in all Europe, perform feats of daring horsemanship that make even our reckless cowboys take notice and admire them.” Boston Globe, June 16, 1907.

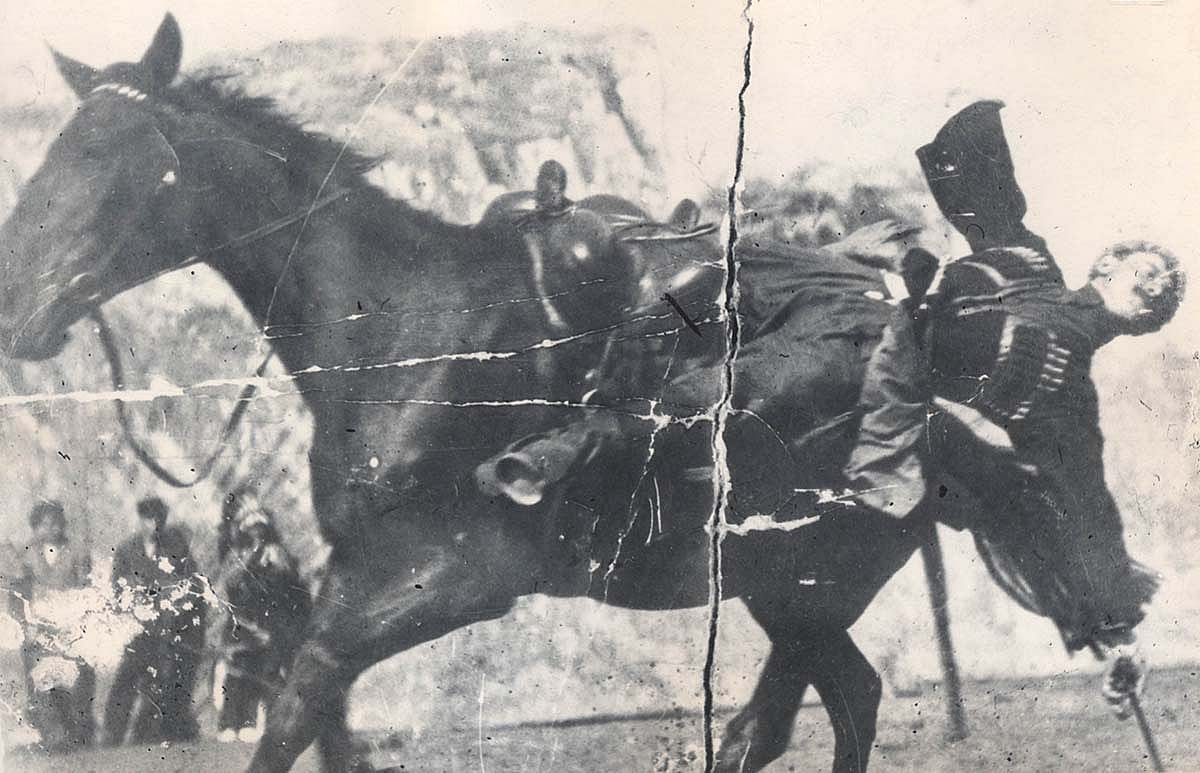

- “The most thrilling riding was done by the Cossacks, standing on their high saddles and riding at breakneck speed, or dashing away with one heel on the saddle and head within an inch of the ground.” The Evening News, Toronto, Canada, July 6, 1897.

Getting in the act

The usual performance of Georgians began with the riders, each dressed in the chokha, taking the stage while carrying their weapons and singing. First, they marched around the arena, and then stopped and dismounted on mid-stage. There, they broke into a new song and started to perform one of the Georgian native dances to the accompaniment of handclaps. Sometimes this dance was executed upon a wooden platform.

The act was usually followed by stunt riding. It represented the perfection of man and horse, and the Georgians did the most unbelievable stunts while galloping. The riders performed a series of maneuvers including standing on their heads or standing upright in the saddle, riding three horses simultaneously, jumping to the ground and then back up on the horse, and picking up small objects from the ground. One of the tricks most popular with the spectators was the rider at full gallop, standing on horseback, and shooting.

The riskiest tricks were carried out only by a chosen few. One of these tricks had the rider removing his saddle and dismounting while riding at a full gallop, and then remounting to fix the saddle back on a horse. This trick-riding style was called “dzhigitovka,” a Turkish word taken to mean “skillful and courageous rider”; the word in Georgian is “jiriti.”

Some Georgian sources claim, rather unconvincingly, that they rode the Georgian breeds. That hardly seems possible, first because it was very expensive to transport a horse across the Atlantic. Second, as I know, it was prohibited by quarantine regulations. (One rider recalled that American horses needed time to get accustomed to their way of riding).

The Cossack saddle also attracted much attention with the July 7, 1904, issue of Iowa’s Neola Reporter, observing, “…Its chief peculiarity, seen from the sides, is two thin pads, fore and after, resembling loaves of bread. A closer examination shows there are four of these pads. The Cossacks stand up in their stirrups with two or three pads on, before and behind his legs. They [the pads] are stuffed with horsehair.” These saddles were not cheap; an ordinary Cossack saddle cost $75; the one custom made for well-known rider Alexis Georgian-Gogokhia cost $275.

Life in the traveling show

In general, the Georgians’ decision to travel to distant lands was based on financial hardship: Touring meant profits. However, on occasion group leaders were targeted with bribes in their native villages. Their American employers paid relatively good money, up to $40 – $50 per month or 100 rubles. It was a huge amount as the price of a cow in Georgia in those days was three to five rubles.

It must be said that not all of the riders went to America voluntarily. A Gurian rider Vaso Tsuladze, known by the name Sam Sergie (performing during 1911 – 1914 and reportedly working in wild west shows after 1917), with his brother Onophre—also a future Wild West performer—fled to the United States following a train robbery. It was said that during the robbery several people were killed. Later, Tsuladze used to show off a gold cigarette case engraved with a double-headed eagle, boasting that he took it from a Russian army officer.

In America, Tsuladze changed his name to Sam Sergie. This was not uncommon as the Georgians typically took on nicknames since their real names were unpronounceable to the show’s organizers and to the public. The show’s financial manager even had to call them by numbers on payday. Sergie died in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1965 at the age of 81. He was an owner of a café, Sam’s Club, and word has it that his lawyer took all his belongings after his death. Sergie’s Georgian friends in the United States protested but couldn’t do anything at the time to stop the confiscation.

Unfortunately, the riders were not insured against tragic accidents. Who can count how often they broke their arms and legs, or how many might have died after such accidents? For instance, on July 3, 1901, an unknown Gurian rider died during a performance of Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show in Iron River, Michigan. On October 28, 1907, another unknown Georgian rider died during a performance of the same Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show in Amarillo, Texas, and Khalampri Pataraia was killed in Louisa, Kentucky, in 1914.

The Wild West show’s female employees brought more grace to the Georgian performances. Five Georgian ladies used to participate in these shows in the United States: Frida Mgaloblishvili, Kristine Tsintsadze, Babilina Tsereteli, Maro Zakareishvili-Kvitaishvili, and Barbale (Barbara) Zakareishvili-Imnadze. After the Russian Revolution, Barbale and her husband, rider Christephore Imnadze, stayed in America and continued to perform. One of the highlights of Barbale’s act was her riding with the American flag in her hands while standing on the shoulders of two riders on galloping horses. Barbale Imnadze died in 1988 in Chicago.

Georgian riders after 1917

World War I, the 1917 Bolshevik coup, and Georgia’s annexation ended the Georgians’ voyages abroad. Those Georgians who found themselves stranded in the States, mostly in Chicago, continued performing in the Miller Brothers show and in the Ringling Brothers circus, and returned to their homeland only when the war was over. Many Georgians settled in the U.S., raised American families, and lost ties with their homeland. In one case, a rider who had a family in his native Guria, wed an American woman, and returned to Georgia after a while. But when he was ready to return to the States, the Bolsheviks refused to let him leave the country, and he committed suicide.

Hard times were ahead for those who did return to Georgia. Thinking they all were American spies, the Bolsheviks either imprisoned or exiled the riders. Many had to destroy all evidence and photographs of their trips abroad in order to survive the new regime’s iron hands. There were cases when riders were forced to sign documents in which they promised never to mention America or Europe again.

The Bolsheviks confiscated all the precious gifts and souvenirs the riders had received. Usually, these mementos surfaced in the houses of the party principals. Daughters of rider Pavle Makharadze recalled, “They used to take different things that had been brought from the United States from the families of all riders. Finally, they took a comb and a tab from our family. My mother was so horrified that she fell ill. She was always waiting for the Bolsheviks to come again.” Nervous stress was too much for many: Some committed suicide; others died in oblivion.

The Georgian riders, so long misnamed, had no desire to become famous or make history. They were simply doing what they did best to make a living and support their loved ones. These trick riders who performed for Buffalo Bill and other American showmen might well be viewed as the first Georgian ambassadors to the United States. The connection between Buffalo Bill and Georgian trick riders represents one of the oldest known relationships between Georgia and the United States of America.

About the author

Irakli Makharadze (b. 1961) is no stranger to the many resources at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. The researcher and filmmaker has produced several popular documentary films such as Riders of the Wild West, Italian Opera in Tbilisi, and Artist Dimitri Shevardnadze. For many years, he was a host of various Georgian television programs regarding American film, culture, and contemporary music. In addition to his successful film career, he has spent years documenting the unique equestrian history of Georgia and the first riders who reached America in the 1890s. He published Georgian Trick Riders in American Wild West Shows, 1890s – 1920s in 2015.

Post 314

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.