The Spiritual and Cultural Legacy of Horses in Native American History

Horses have held a cherished and iconic place in American culture for centuries. Celebrated for their strength, speed, and versatility, they have played essential roles across many facets of life; serving in agriculture, improving transportation, and offering companionship through recreation and sport. Horses have long earned their place as exceptional partners to people across the country. Yet, one of the most heartfelt chapters in their story unfolds through the spiritual connection Native American communities share with their horses. For Native Americans, horses approach the sacred—respected as partners in life, symbols of freedom, and carriers of tradition.

A Return to the Plains: The History of Horses in North America

Though Equus originally appeared in North America, they vanished from the continent around 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. It wasn’t until the early 1500s, when Spanish explorers like Hernán Cortés brought horses back to the Americas, that these animals returned to the land. From just a handful of horses brought to Mexico in 1519, the animals spread rapidly across the continent.[1]

For a long time, many believed horses didn’t reach the American West until after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, based mostly on European records. However, recent archaeological finds at places like Paa-ko Pueblo in New Mexico and sites in Idaho and Wyoming suggest that Native peoples already used horses by the early 1600s. A historian at the university of Nothern British Columbia, Ted Binnema explain that “[The evidence] is pretty much in line with what historians have been writing for the last 20 or 30 years. The entire military history of the Plains seems to make sense with this timeline.” [1] These discoveries reveal that horses became part of Indigenous life—and even spiritual practice—much earlier than previously thought.

Horses in Indigenous Life and Culture

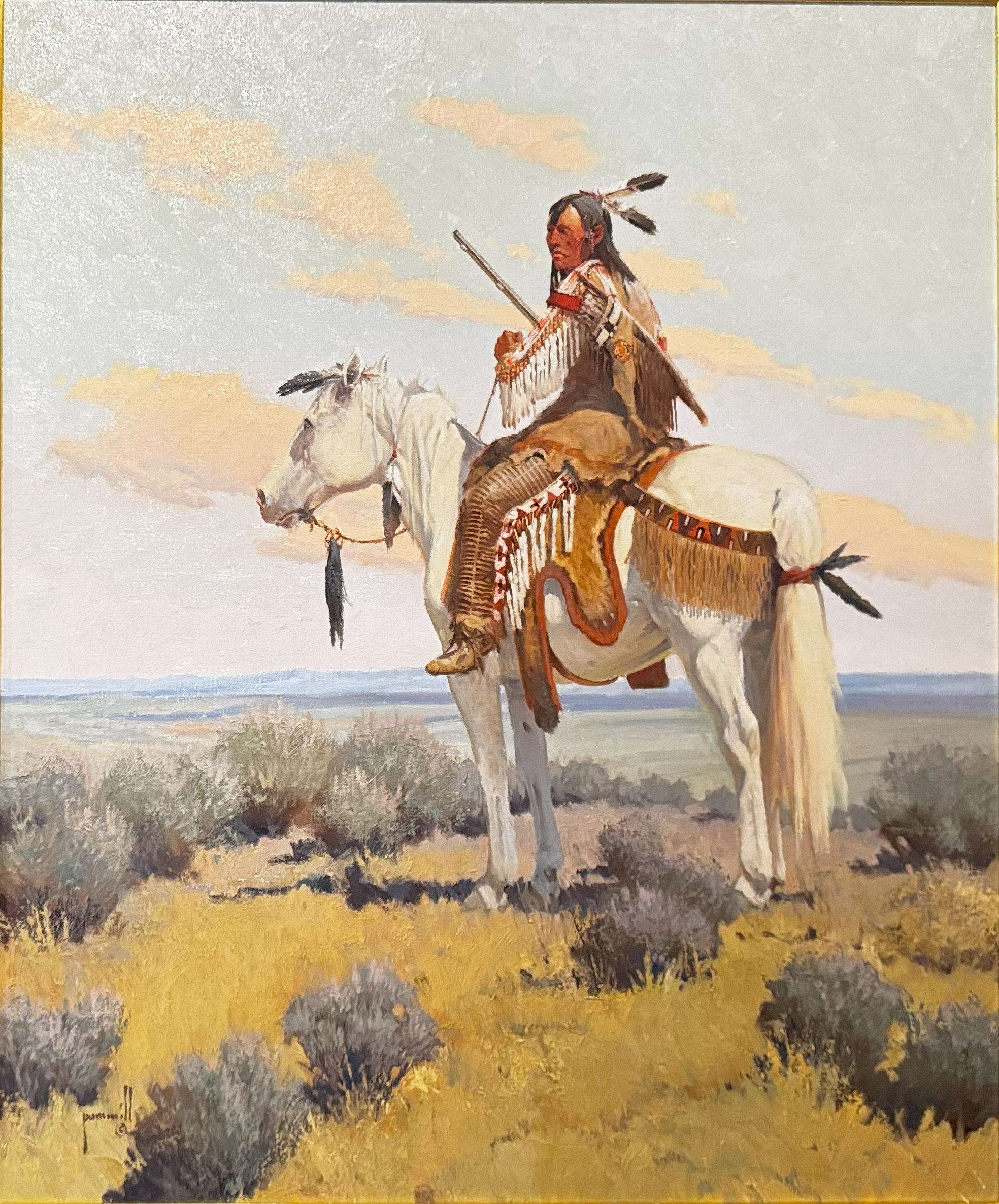

The implementation of horses transformed Native American life, especially among the Plains tribes stretching from the Rocky Mountains to the Missouri River. Horses became essential for hunting buffalo, traveling long distances, engaging in warfare, and trading. Breeds like the American Quarter Horse helped many tribes live more mobile and expansive lifestyles. Beyond their practical roles, horses also became symbols of wealth, leadership, and status.

But horses meant even more than that. They held deep spiritual and emotional significance, and still do today. The Lakota, for example, called horses Sun’ka Wakan, meaning “Holy Dog” or “Mysterious Dog.” [2] This name reflects the deep connection they have with this animal. To Native Americans, horses symbolized healing, strength, and a deep emotional intelligence that transcended the physical world.

In many Native communities today, equine therapy serves as a powerful tool for helping people heal from trauma and develop emotional resilience. Horses, with their innate sensitivity to sound, scent, and body language, are uniquely attuned to human emotions, making them ideal partners in therapeutic settings, much like therapy dogs, but with a deeper, often spiritual dimension.

As noted by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, Indigenous cultures have long regarded animals as spiritual companions, bound to humans by a shared destiny. The horse, in particular, embodies this belief: not merely a means of transport or labor, but a sacred presence, a healer, guide, and trusted friend whose role extends far beyond the physical world. [3]

As The People of the Horse by National Geographic says:

“These horses—they’re everything to us. They tell you when the seasons are going to change, when storms are coming, when bad people are around, and when good people are around. They are teachers, someone you can talk to. Your best friend—some days, your only friend.” [4]

Honoring Horses Through Art and Craft

Native Americans expressed their respect and love for horses not only through actions but also through art and decoration. The gear horses wore saddles, blankets, and masks which reflected the tribe’s identity and honored each horse’s unique qualities. Mandy Foster (Lakota) shared about her horse, Joe:

“I grew up surrounded by animals. My dad gave me my first horse when I was 8. My family are cattle ranchers, and rodeo is super important—it helps develop skills we use on the ranch. Indians have traditionally regarded the animals in their lives as fellow creatures, and they share a common destiny. That intimate bond between humans and animals is nowhere so evident or powerful as in the case of the horse.” [3]

Early saddle blankets in Native communities were crafted from the hides of animals such as bison, deer, or mountain lions; materials that reflected both the resources available and a respect for the natural world. The Lakota Tribe continues to honor this tradition, now using cloth or canvas blankets featuring two long strips of fabric, a design that mimics the contours and function of the original animal hides. These blankets, often adorned with beadwork and porcupine quill designs, preserve artistic practices that flourished in the early 20th century. [3]

Saddles were typically constructed from wood and wrapped in rawhide, which was then hardened through careful drying. The pommels, (the raised front portion of the saddle), were crafted from elk or deer antlers, chosen for their natural strength and curvature. The Crow tribe, were known to embellish the pommels and stirrups with intricate beadwork, blending utility with aesthetic expression.

Saddle design also reflected cultural roles and practical needs. Women’s saddles were generally larger and built to carry supplies during long journeys, while men favored lighter saddles or simple pads that offered greater mobility during hunts or combat.

Among the most striking equine adornments were horse masks, custom-fitted coverings made from hides or canvas, often decorated with powerful symbols such as horns, which represented strength and protection. While these masks were not used in battle due to their potential to obstruct a horse’s vision, they held ceremonial importance and were frequently worn during parades and spiritual gatherings. By the early 1900s, horse masks had evolved into richly beaded works of art, each bearing distinctive tribal patterns that identified not only the horse, but also its rider and tribe.

Breeds and Regional Traditions

Different tribes developed strong bonds with specific horse breeds. The American Quarter Horse, for example, came from mixing Chickasaw ponies with English Thoroughbreds in the 1700s. Southeastern tribes like the Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Creek were among the first to capture and raise horses introduced by the Spanish.

In the Northwest, the Nez Perce tribe bred the Appaloosa—a spotted, agile horse famous for endurance. After the U.S. Army broke up their herds following the Nez Perce War, 20th-century preservation efforts helped save the breed. Today, the Appaloosa represents the tribe’s resilience and strength.[5]

Indian Relay Racing: Tradition in Motion

One of the most exciting ways the Native American-horse bond lives on today is through Indian Relay Racing. This fast-paced, high-risk sport thrives in the U.S. and Canada, with its heart at the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Idaho, home to the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes.

Though the modern sport dates to the early 1900s, oral histories link it to racing traditions from as far back as the 1860s, possibly connected to the Pony Express. The race is thrilling to watch and depends heavily on trust between rider and horses. [6]

Each team includes three people: the rider, a “mugger” who catches the horse after each lap, and a “back holder” who readies the next horse. Riders race bareback, switching horses at full speed for three laps. The skill and courage on display reflects a powerful bond between human and horse.

Indian Relay events often take place at cultural festivals like the Shoshone Bannock Festival and the World Championship Relay in Wyoming. There are races for men, women, and youth, ensuring this tradition passes to future generations.

A Lasting Legacy

The relationship between Native Americans and horses is built on trust, healing, and respect. From their return to North America centuries ago, to their role in spiritual beliefs, art, and modern sports, horses have shaped how Native peoples live, travel, and see the world.

Today, horses thrive in Western culture and Native American identity. Their strength, awareness, and loyalty continue to make them companions, teachers, and healers.

1. Horse nations: Animal began transforming Native American life startlingly early | Science | AAAS, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.science.org/content/article/horse-nations-animal-began-transforming-native-american-life-startlingly-early. ↩

2. Native Hope, “Native American Animals: Horse (Sun’ka Wakan) Is a Relative to the People,” Native Hope Blog, November 16, 2022, https://blog.nativehope.org/native-american-relative-horse. ↩

3. Horse | Caballo, The Value of the Horse in Native Cultures, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 2013, https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/resources/Horse. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

4. Sarah Joseph, The People of the Horse, National Geographic, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKi-8K_7xwo. ↩

5. “Native American Horse Breeds: A Song for the Horse Nation – October 29, 2011 through January 7, 2013,” National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, accessed August 8, 2025, https://americanindian.si.edu/exhibitions/horsenation/breeds.html. ↩

6. et al., “Far from the Finish Line: Indian Relay Horse Racing Perseveres through Generations, despite Its Risks,” NMAI Magazine, Summer 2024, Vol. 25 No. 2, accessed August 8, 2025, https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/indian-relay-horse-racing. ↩

Written By

Emma Brence

Emma Brence is a summer intern at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West and a full-time student at Laramie County Community College.