The Birth of the American Long Rifle

If any firearm were to define the colonial and foundational years of the American experiment it would undoubtedly be the American long rifle in all its variants and offshoots from Pennsylvania to Kentucky. The image of the Appalachian mountain-man in his buckskin and moccasins charting though the then unknown frontiers of the Ohio valley and beyond dominates our cultural perspective of those who braved the wilderness to go west. Furthermore, our national martial culture upholds the civic soldiers and militiamen who faced the mightiest empire in the world to secure independence for his state by the might of his rifle as the highest virtue of service. Yet the origin of the American long rifle is steeped in traditions and trades that predated the both the rifle, the men, and the republic it served.

Like most American traditions to find the true origin of them one must look to Europe. In the case of rifles no nation was as invested in their development than the various German states of the H.R.E such as Hesse. Which utilized these rifles for both hunting as well as for equipping Jäger units which were skirmishers and marksmen for their state armies. Many of the gunsmiths and tradesmen who produced the handmade and highly individual weapons would sail to the new world seeking to start a new life and find their fortune in America.

Upon arrival there was a high demand for firearms in all aspects of life from both defense to sustenance hunting as well as the more profitable fur trade. Muskets of all types and patterns were in widespread use; however, those German gunsmiths were in a unique position to dominate large elements of early American firearm culture and trade due to factors that plagued the new world. Chief among them was a chronic shortage of gunpowder, forcing colonists and hunters to make every shot count both in trade and in war. The shortages were a result of faulty production methods in colonial powder houses along with poor storage and distribution of the vital powder making it difficult to adequately store enough powder for military needs and ensured that quality European powder commanded a high price when it was inevitably imported.

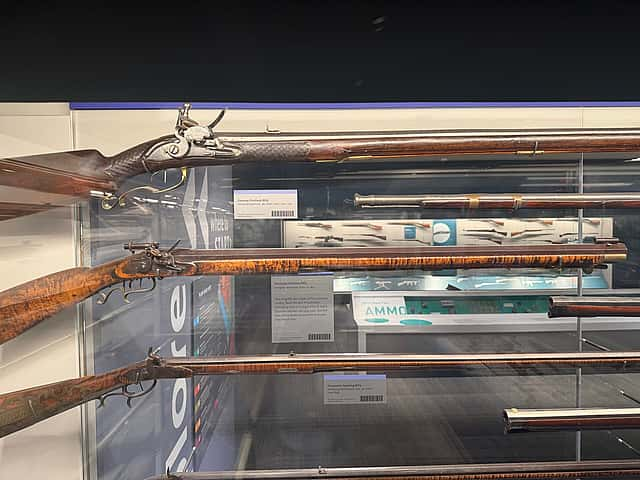

To adapt to these new circumstances the Jäger rifle transformed to tailor to the needs of hunters and frontiersmen. The shorter and handier barrels of the older rifles were replaced with ones considerably longer than even standard military muskets to ensure accuracy over distances more than 200 yards. This was paired with the calibers of many of these rifles being decreased from typical .60-.75 to between .36-.54 caliber, allowing for trappers and hunters to pack light and utilize less powder per shot, ensuring that the rugged frontiersmen could do more with less. Any concerns over lethality were diminished due to the sharp increase in velocity, because of the lighter projectile and longer barrels, along with the greater ease of hitting vital organs on large game compared to smoothbores. Much like they had been in Europe, each rifle and each gunsmith had their own flair and design choices. So, while many of the rifles tend to be consolidated into being called either a Pennsylvania or Kentucky, each rifle was its own artform made by one man to needs of one client. Such was their popularity even George Washington, then a colonel in His Majesties British Army, commissioned a specialty rifle for hunting foxes and over the course of his life would purchase more when prior ones were lost or destroyed.

Bottom Muzzle: American Long Rifles were usually made in smaller calibers (.36-.54) to optimize for hunting game in the new world.

It would not take long for the rifle to be utilized in the various wars that would be fought in the new world. In the French and Indian war both American colonials as well as French militia and troops utilized rifles in much the same skirmish and sharpshooting tactics as had been used by both German Jägers as well as the various native American tribes that took part in the dense woodland fighting. When terrain was unforgiving, large lines of infantry that would have dominated in the open fields of Europe or the American coast were cumbersome and could not effectively mass their fire against a dispersed foe in cover. Here the rifle came into its own as a specialty weapon to be utilized when traditional tactics would be found wanting.

When it came time for the Americans to throw off the yoke of the empire the riflemen became a dominating symbol of American individualism and independence. The image of a man in his every day clothing sniping out a British officer or gunline from beyond the range of return fire persists in American popular culture to this day. yet with it comes both the mythos and the historical reality of the American rifleman. In the early war the riflemen were organized into a separate corps of marksmen not under the command or discipline of the regular army officers, while they were the best at their trade, their lack of discipline led to mutinies and desertion among their ranks, as well as conflict with the common soldier and officer due to pay differences. As a result, Washington was forced to abolish many of their privileges and place them under regular army command.

Furthermore, when it came time to supply the newly raised regiments of the Continental Army many officers complained of being over supplied with rifles and having a critical shortage in muskets. While at first this might not seem like a real issue, the problem arises when you compare the rate of fire of a musket to an American long rifle. which is about twice as fast compared to rifles as you do not need to fight the rifling when ramming home a tightly packed ball on a smoothbore. For the officers of the Continental Army the mass of fire generated by muskets, and the cold steel of the bayonet (most rifles did not have mounts for bayonets) were far more tactically important than being able to make picked shots. Ultimately it was victories by the line regiments at Saratoga, Yorktown among several other battles that would win independence. While the riflemen were present for many of those battles, especially in the northern theater and proved themselves an effective force that could break the British chain of command or morale, as well as become some of the best skirmishers and marksmen of the war, they were a supplement to the line infantry rather than a replacement, let alone the force that won the revolution.

However, the cultural sprit of the rifleman would live on even in the army proper with many officers’ generations later pointing to the value of ever more accurate rifle fire. and in the fact that those riflemen would return to the wilderness after the war only to be called upon to go west or to rally to the flag in the young nation’s future wars.

If you would like to further your understanding and experience with firearms of the Revolutionary War be sure to stop by the Buffalo Bill Center of a West for the Arms of the Revolution exhibition launching April 17, and consider booking an Exclusive Tour to learn more about the American Long Rifle and get hands on with genuine artifacts in our collection.