Exhibits

Western Art Themes in the Whitney

The West Defined

People often define the American West by geography, though any line drawn on a map invites debate. Artists shaped how the nation imagined the West through powerful landscape paintings. Starting in the nineteenth century, many portrayed wide-open, fertile lands waiting for settlers. In reality, much of the region held dry, challenging terrain—or thriving Indigenous communities. Whether rooted in fact or fantasy, these images gave viewers stirring visions of western horizons. At the museum, staff celebrates the many ways people define “the West,” while focusing on artwork inspired by the Northern Plains and Rocky Mountains. The collection grew from this regional core, and curators continue to strengthen it through thoughtful acquisitions.

Native Identity & Representation

How do artists’ cultural backgrounds, historical moments, and personal visions shape the way they portray themselves and others? Much of the Whitney’s collection offers insights into American Indian life through both Native and non-Native perspectives. For nearly two centuries, non-Native artists have shown deep fascination with Indigenous peoples and events. Many drew heavily on European artistic traditions, repeating similar themes with little variation. They often highlighted striking elements of Native dress—feather bonnets, beaded moccasins, intricate patterns—to create generalized images that stood in for complex identities. While some portrayed Native communities with nuance and vitality, most reinforced stereotypes that still influence perceptions today.

Yellowstone

Dense forests, crystal-clear lakes, abundant wildlife, candy-colored canyons, and gushing geysers—these features of Yellowstone have captivated artists for generations. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, scientists and military explorers investigated the region, returning with accounts of exotic plants, animals, and otherworldly geology that confirmed earlier fur trappers’ tales. Enthralled by these reports, artists from the East Coast and beyond seized the chance to portray and share Yellowstone’s wonders. The park’s allure endures as artists continue gathering in this vast natural studio. From historical to contemporary works, the Whitney Western Art Museum’s collection of Yellowstone art celebrates the park’s wild beauty.

Charles M. Russell

At 16, Charlie Russell left Missouri to chase adventure in Montana Territory. He worked as a ranch hand and spent his free time sketching and sculpting western scenes drawn from life and imagination. Self-taught yet dedicated, Russell quickly gained recognition as one of the region’s foremost artists. Admirers praised his ability to capture the American West during a time of sweeping change and to portray earlier chapters of its history. Through drawings, paintings, and sculptures, he told stories of western peoples, landscapes, and wildlife—sometimes drawn from personal experience, sometimes from nostalgic longing, often blending myth and reality. The Whitney Western Art Museum holds a remarkable Russell collection: 50 paintings, 12 illustrated letters, 97 drawings, and 194 sculptures, displayed as time, space, and object safety allow.

Fredric Remington's Landscape Studies

Frederic Remington gained fame for portraying the “Old West” and military subjects, yet late in life he shifted his focus to landscapes. He produced vibrant works that highlighted the distinctive light and atmosphere of the American West. The small, impressionistic oil paintings on view showcase his landscape studies from the early 1900s. A few appear finished and signed, while most remain quick sketches. Remington began and sometimes completed these paintings outdoors during trips to Wyoming or near his home in upstate New York, working rapidly to capture colors transformed by shifting sunlight and weather. Notice the hues he uses to convey light: lavender streaks shape shadows on a sandy riverbank, and dots of orange, gold, green, and blue animate a sun-dappled forest floor. For Remington, these paintings celebrated the expressive power of color.

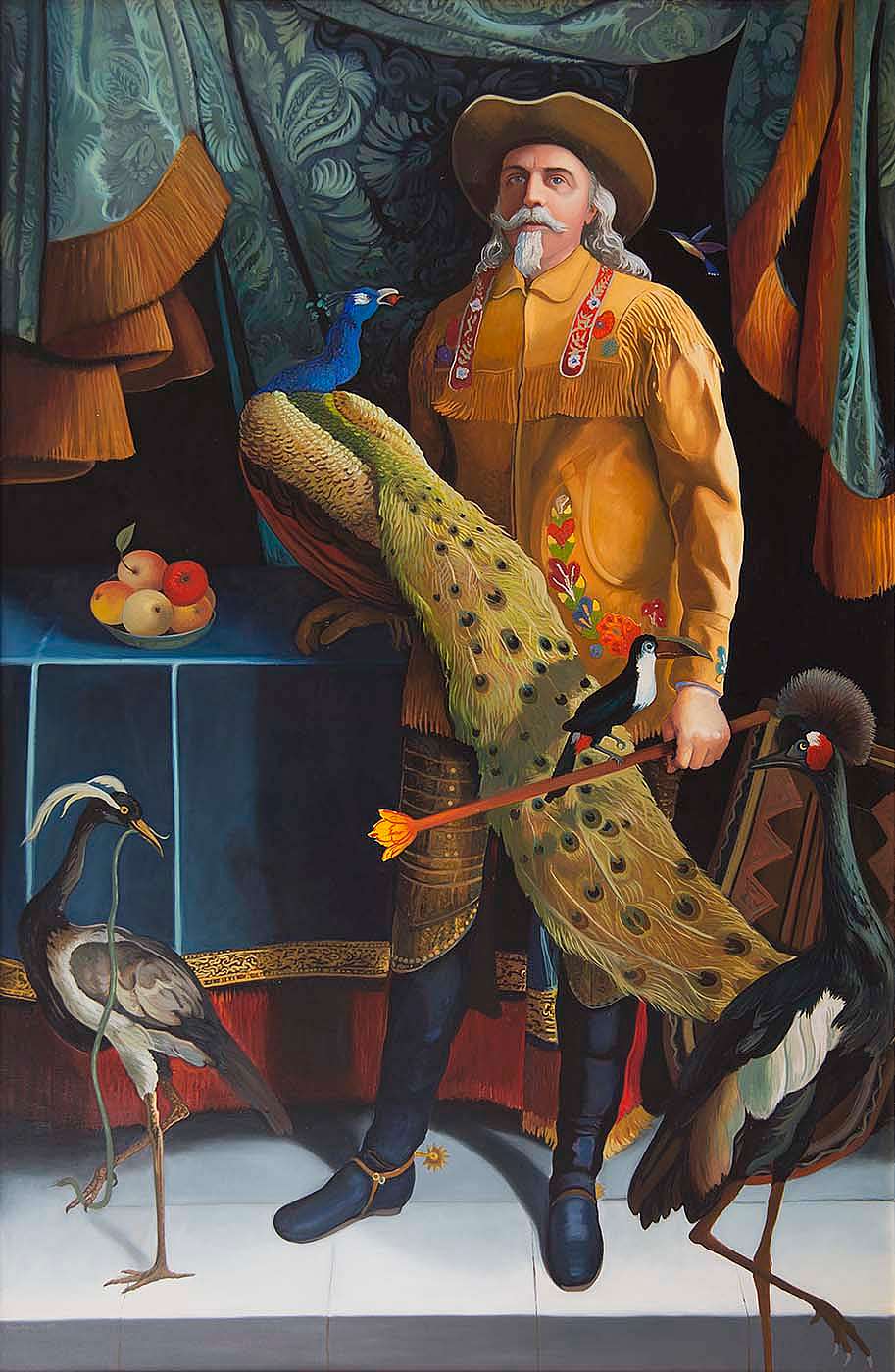

Buffalo Bill in Art

Over the years, artists have portrayed William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in an extraordinary range of materials and styles, from grand oil paintings and bronze sculptures to posters, photographs, and illustrations. Buffalo Bill eagerly encouraged these portrayals, commissioning celebratory artworks and working closely with artists to shape his own image. He understood the power of visual storytelling and cleverly used art as a tool for self-promotion, ensuring that his likeness spread far and wide alongside his legend. Because of the vast circulation of these images, Buffalo Bill became one of the most recognizable figures of his era, and his face remains familiar today. Each portrait offers a unique interpretation, yet most depict him with flowing hair, a pointed goatee, and his trademark cowboy hat—an instantly identifiable silhouette. When drawing, painting, or sculpting people, artists make deliberate choices that influence how audiences perceive their subjects. Depending on the artist’s point of view—or that of a patron commissioning the work—viewers might see Buffalo Bill as a tireless army scout, a skilled and deadly hunter, a confident showman, or a completely different persona. Together, these varied depictions reveal as much about the artists and their times as they do about Cody himself.

Wonders of Wildlife

Wildlife and nature have long captivated artists working in the West, and animals frequently take center stage in depictions of the region by both Native and non-Native creators. Some of America’s most iconic species, such as the American bison and the bald eagle, live only in the West, while countless other wild animals inhabit its plains, forests, and mountains. Livestock like horses and cattle—central to the region’s cowboy and ranching heritage—also populate western scenes in great numbers. With such remarkable biodiversity, artists past and present have naturally turned to animals as powerful subjects. William Herbert Dunton (1878–1936) embraced this tradition in Timberline (1932), an oil painting given in memory of Hal Tate by Naoma Tate and the Family of Hal Tate. Visual representations of animals shape how viewers think about wildlife and the natural world. Artists can highlight physical beauty, symbolic meaning, or both, choosing whether to portray animals as spiritual beings, loyal companions, hunting trophies, scientific subjects, or vital resources for human survival. Each artistic choice influences how audiences perceive and value the creatures that define the West.