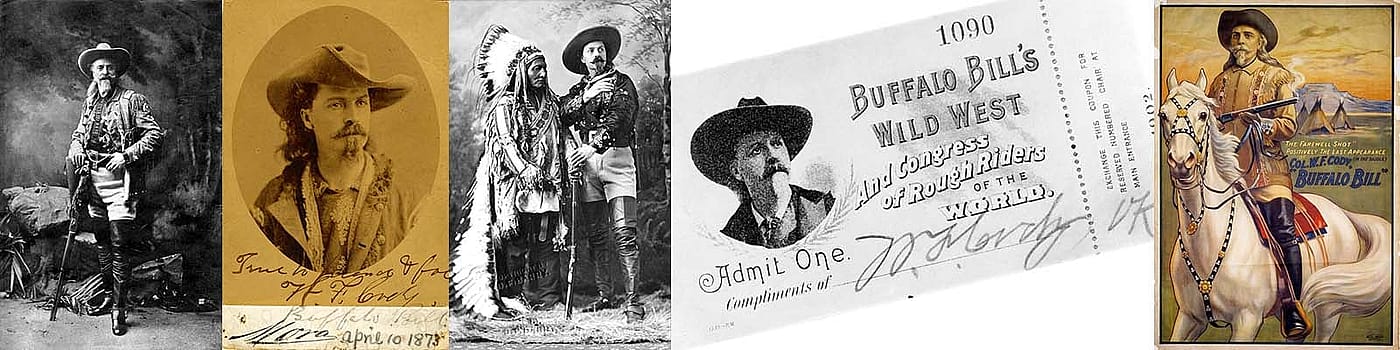

William Frederick Cody

William Frederick Cody

By Paul Fees, Former Curator

Buffalo Bill Museum

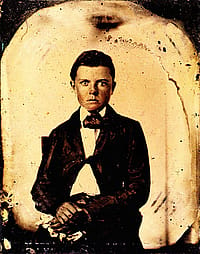

William Frederick Cody (1846 – 1917), the boy who would become Buffalo Bill, was born in a log cabin near LeClaire, Iowa Territory, on February 26, 1846. His father, Isaac, worked variously as a trader, a surveyor, and as overseer for an absentee landowner.

Isaac Cody himself was a product of westering pioneers. The first Codys in America were Huguenots who fled France for the Isle of Jersey to escape religious persecution. By 1698 they owned land in Massachusetts. Isaac was born in Ontario in 1811 and grew up in Ohio. Twice widowed, he wed schoolteacher Mary Bonsell Laycock in 1840 in Cincinnati. She was descended of Pennsylvania Quaker pioneers. With Martha, Isaac’s five-year-old daughter from his first marriage, they moved to Scott County, Iowa, where six of their seven children were born: Samuel, 1841; Julia, 1843; William, 1846; Eliza, 1848; Helen, 1850; and May, 1853.

Only prolonged illness kept Isaac from striking out for California during the gold rush. After the accidental death of Samuel in 1853, the Codys headed west, moving briefly to Missouri then to Kansas where Isaac supplied hay and wood to Ft. Leavenworth and traded with the Kickapoo Indians. Another son, Charles, was born in 1855. Isaac, a man of principal and an active civic leader, was stabbed in 1854 while making a speech against slavery. The attack did not deter him from his economic or political activities, but its lingering effects led to his death in 1857.

Bill (“Willie” to his family) and Julia supported and cared for the younger children and their ailing mother. Martha left to marry and died shortly thereafter. Bill took a job as a herder and mounted messenger with Russell, Majors, and Waddell, the Leavenworth freighting firm and organizers of the Pony Express. A year later he accompanied a wagon train to distant and exotic Fort Laramie.

During the next two years young Cody trapped beaver, trekked to the gold fields of Colorado, and found time for several months of schooling. He also joined (“to my shame,” he admitted) in some of the “border war” mischief by anti-slavery gangs of Jayhawkers.

It has been generally assumed, not without controversy, that Cody rode for the Pony Express at age fourteen or fifteen. Because of internal contradictions in his autobiography, scholars have made a good argument for denying his participation. However, most of his actions in 1860 – 1861 cannot be independently verified. The crucial role he and his Wild West show later played in commemorating the Pony Express, and his close friendship with men central to the Pony Express, both cloud the issue and in some ways make the debate irrelevant. In the absence of other records, the most it may be possible to say is that as a skilled horseman, an adventurous youth, and an erstwhile employee of the company, Bill was in the right place at the right time.

Mary Cody died on November 22, 1863. Bill mourned deeply. Early in 1864 he enlisted in the 7th Kansas Cavalry, a volunteer Union regiment that included many of his Jayhawking comrades, and fought honorably to the end of the Civil War. In St. Louis he met Louisa Frederici and married her there in 1866. They moved to Kansas to be with his family, which had been further bereaved by the death of little brother Charles late in 1864.

Bill and Louisa had four children, only two of whom survived to bear children of their own. Arta Lucille (1866 – 1904) was born at Leavenworth; Kit Carson (1870 – 1876) and Orra Maude (1872 – 1883) at Ft. McPherson, Nebraska; and Irma Louise (1883 – 1918) at North Platte.

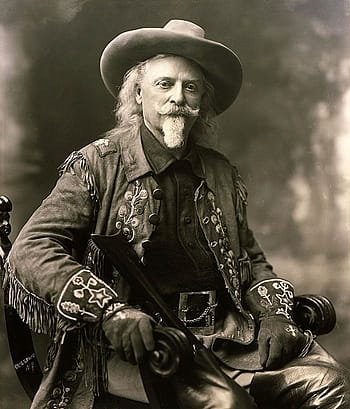

Like his father, Bill seldom stayed long at home. After a stint as a stagecoach driver and a half-hearted effort at inn keeping near Leavenworth, he set out to make a living on the plains. His talents and physical gifts combined with an apparent fearlessness made him successful at contract jobs for the Army and railroad. Supplying 4,280 buffalo to feed railway construction workers during eight months in 1867 – 1868 earned him his nickname, “Buffalo Bill.” General Philip Sheridan considered him a modest and well-spoken natural leader and made him chief scout for the 5th Cavalry in 1868. During his years as scout (1868 – 1872; 1874; 1876), he fought in nineteen battles and skirmishes, was wounded once, was cited and rewarded for valor and “extraordinarily good services,” won the Congressional Medal of Honor for gallantry, and a month after Custer’s defeat, he killed a Cheyenne warrior in hand-to-hand single combat.

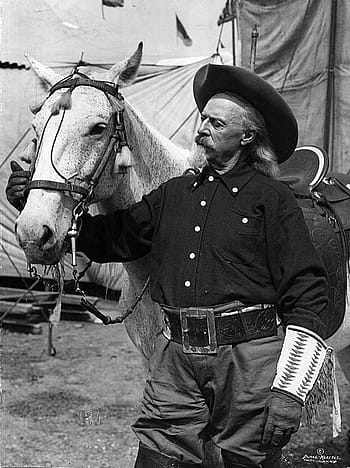

Sheridan assigned Cody in 1872 to guide the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia on one of the century’s most celebrated hunts. The resulting publicity helped launch Cody’s acting career when later that year he and Texas Jack Omohundro opened in Chicago in “Scouts of the Prairie” written by dime-novelist Ned Buntline. The “flavor of realism and nationality” that one perceptive critic found in the melodrama defined not only Cody’s stage plays for the next dozen years but also his great arena show, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (1883 – 1913). Better than any other medium of its day, the Wild West tied America’s development to “the winning of the West.” The show put it into a clear narrative format and presented it to millions of people in the U.S. and abroad. In Europe, Buffalo Bill is still one of the most recognizable of Americans.

Cody invested his earnings in the modern West—mining in Arizona, ranching in Nebraska, town building in Wyoming, filmmaking, and tourism. Most of his ventures did not return profits in his lifetime. When his Wild West show failed in 1913, his indebtedness forced him to tour through 1916 as an attraction with other shows. His death in Denver on January 10, 1917, of kidney failure, led the press to lament “the passing of the Great West.” He was accorded a state funeral, still perhaps the largest in Colorado history.

In his person, Cody reconciled for Americans the seemingly contradictory values of individualism and wilderness on the one hand with those of civilization and progress on the other. A Chicago newspaper editor summed it up: “He has been more than picturesque; he has been worthwhile.”

Learn more about the Buffalo Bill Museum

Additional Reading:

- Hedren, Paul. First Scalp for Custer. Lincoln, Nebraska, 1987.

- Hutton, Paul Andrew, ed. Ten Days on the Plains. Dallas, Texas, 1985.

- Rosa, Joseph and Robin May. Buffalo Bill and his Wild West. Lawrence, Kansas, 1989.

- Russell, Don. The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill. Norman, Oklahoma, 1960.