A Boy and His Bird, or more accurately, a red-tailed hawk who tolerates the presence of a boy

By Sarah the Intern

It was earlier in my experiences with the birds, probably around my first week, when a woman asked an interesting question. She wanted to know if we had each formed a “bond” with the birds we were handling. Since then, I have been pondering the correct answer to that question. Now that I have spent almost a month with these amazing animals, I feel prepared to try and answer it.

The quick answer is no, not in the way she was thinking. Bird club is not exclusive. Anyone with a decent temperament can learn to handle birds. Handlers do not form deep affection-based links with these animals. They’re not even particularly affectionate towards us, at least not in the way that people think of affection. The preference of a bird to one handler or the other is based mostly on how familiar the bird is with said handler.

The longer answer is… sort of. The birds may not form deep, lasting friendships with us as handlers, but we do have relationships. The birds feel a certain comfort with us the more they see us and recognize us. For example, Melissa can hold Suli (turkey vulture), fly Suli, and even play with her. A stranger couldn’t even approach her without her freaking out. I’ve learned that birds do have personalities, usually dictated by their species. Within that personality, individuals have their own quirks. There’s also a lot of personification on the human end. To help you gain a better understanding of this concept, I’m going to walk you through my own relationships with each of the birds. Today I’ll be talking about Isham, the red-tailed hawk.

Isham was the first bird I held on my glove, and he’s been guiding me through the bird handling process ever since. He watches my free hand critically as I tie him to my glove, as if to say “Good form, but you really should be doing that quicker.” When I leave a door open and have to go back, he patiently adjusts his grip and a stern glance informs me that I must remember not to change direction so quickly with a bird on my arm. He has a strict set of rules which every handler should abide by: he is there to be admired but never touched, handlers should be polite and enter doorways first, humans must stay where they can be kept an eye on at all times, and a gentleman operates best when given his space.

Melissa says that Isham is the pickiest eater of any red tail she has ever seen. Guts are beneath him, and should either be removed prior to feeding or shall be retrieved from the Astroturf the following morning. Rabbits are gross, icky things, and you can tell him all day that every other red tail in the world loves rabbits but you would only be wasting your breath. Baby chicks are high in protein and are equally high on Isham’s list of foods that shall not be eaten under any circumstances.

Isham does not like to be watched while he’s eating. If you are patient and quiet enough you will see him hop over to his flat perch and grab a mouse. Then begins the tricky part of getting the mouse back over to the middle of his perch, where he prefers to eat. His missing eye is of great irritation to him as he twitters uncertainly about how best to get where he needs to go. He will lower his body and raise his shoulders, desiring to simply fly the few feet necessary. But then he pauses, troubled by his inability to judge distance. He lowers his wings and hums uncomfortably. This action is repeated several times before he finally takes his leap of faith, and flutters less than gracefully to land at his destination.

Isham is a dancer. He and I dance whenever I come to pick him up. The length of the dance depends on his mood and my confidence that day, but the steps are always the same. I approach, talking to him the whole while. He steps away, surprisingly nimble. I take one step, following his perch towards the flat shelf. He lowers himself, shoulders up, head bobbing, before hopping the rest of the way onto the shelf. I step again, he bobs again, philosophically considering the sturdiness of his corner. I step again. He leaps, finding the corner quite solid after all, his feet scrabbling in the hopes of finding some perch too high for me to reach. I step again, he raises his wings high and twirls in a circle. (This twirl is also known as his dance of discomfort. Rather than launching himself off a handler’s glove as the other birds do, he performs this dance on the glove). These steps may be repeated a few more times before I get close enough to grab the leather straps (jesses) dangling from his legs. Now our dance is near an end. I carefully reach forward. My fingers softly guide the edge of the jess into my glove. Now Isham looks critically toward me, asking if I have him. He hops away, testing my hold on him. Finding it firm and unyielding he hops onto the glove. Our dance is finished.

To me, Isham is my partner in crime, my buddy. He is my guide and my instructor. To Isham, I am a tree that could do with a little less movement and a little more stability. “Drop your arm for goodness sake or I will surely fall off!” But I am getting better. I am recognized, so I am comfortable. He knows my voice, my face, and my movements. He knows I mean him no harm and that my arm is a safe place to stand. To me, he is my friend. To him, I am an acceptable tree.

Falconry Terms in Layman’s Terms

Term: Hood-shy

Falconry Term: A hawk that dislikes being hooded, generally through a fault of the falconer, is hood-shy.

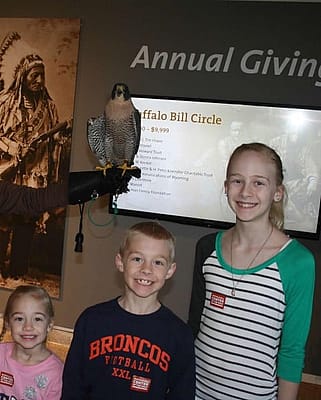

Layman’s Terms: Hayabusa (peregrine). A bird that will bite the hell out of you if you so much as dare to approach her with that horrible terrifying thing. No joke, she will try to kill you. Not our fault, by the way. She came to us like this.

Written By

Melissa Hill

While earning her Bachelor's Degree in Wildlife Management at the University of Wyoming, Melissa began volunteering at Laramie Raptor Refuge and was instantly hooked on birds of prey. Since those early days, she has worked with nearly 70 different raptors at four different raptor education groups in three states. She is a former member of the Education Committee for the International Association of Avian Trainers and Educators (IAATE) and a National Association for Interpretation's Certified Interpretive Guide. When she's not "playing with the birds" she enjoys spending time quilting, crocheting, and exploring the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem with her non-bird family.