Thundering Hooves, Five Centuries of Horse Power in the American West – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 1994

Thundering Hooves: Five Centuries of Horse Power in the American West

By Emma I. Hansen

Curator, Plains Indian Museum

Ed. note, 2014: this article refers to a past exhibition that was displayed at the Center in 2004.

Introduced into North America at Mexico by the Spanish conquistador Don Hernan Cortes in 1519, the domestic horse dramatically shaped and influenced the cultures, economies and ecology of the American West. For more than 400 years, as successive generations of people moved into this vast region, horses and horsemen have played special roles in the changing cultural landscape of the West. The special fall [2004] exhibition Thundering Hooves: Five Centuries of Horse Power in the American West explored the relationship between the horse and the people of the West—the conquistadores, the vaqueros, the Comanche, and the cowboys.

The Conquistadores

Horses are the most necessary things in the new country because they frighten the enemy most, and after God, to them belongs the victory. -Pedro de Castaneda de Najera, Relacion du voyage de Cibola enterpris en 1540

Horses native to the Americas had been extinct for 10,000 years prior to the arrival of Europeans in the fifteenth century. On his second voyage from Spain to the Americas, Christopher Columbus brought 35 horses to the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. By 1500, Spanish ranches on the island bred both horses and cattle and provided horses for expeditions of conquistadores to the Americas. As Spanish armies waged war against ancient Indian civilizations in Mexico and the Southwest, horses became valuable aids in establishing Spain’s control over a large span of the Americas.

Spanish horsemen in the Americas were outfitted with those pieces of knights’ armor which were suited for the climate, including head and neck protectors for their horses. Their saddles, spurs, weapons, and other equipment were adapted for their traditional styles of riding and warfare.

The Vaqueros

Vaqueros brought their families and Spanish traditions of ranching to the North American grasslands in the 1500s. Their work was herding the livestock brought to the Americas by the Spanish, including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and horses. By the mid-1600s, haciendas with large herds of longhorn cattle stretched from Mexico City into New Mexico and became the center of the American ranching economy.

Located far from sources of trade goods, haciendas often were self-sustaining, with artisans producing such necessities as leather saddles and bridles, furniture, clothing and woven goods, and bits and other riding equipment. The finest spurs, or espuelas, covered with incised decorations and silverwork, however, were made for the vaqueros in central Mexico. From the vaqueros of the ranches of New Spain came such innovations as roping from horseback with lariats, branding of livestock, and the charreada, the prototype of the cowboy’s rodeo.

The Comanche

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Plains Indian people had traveled and hunted bison on foot, using dogs to drag their travois and carry their possessions. On the Southern Plains, the Apache were the first to acquire and adapt their way of life to the horse in the mid-1600s. As the Apache built up large herds of horses from those captured from settlements in the Southwest, they were able to travel greater distances for hunting and trade and eventually dominated the Southern Plains.

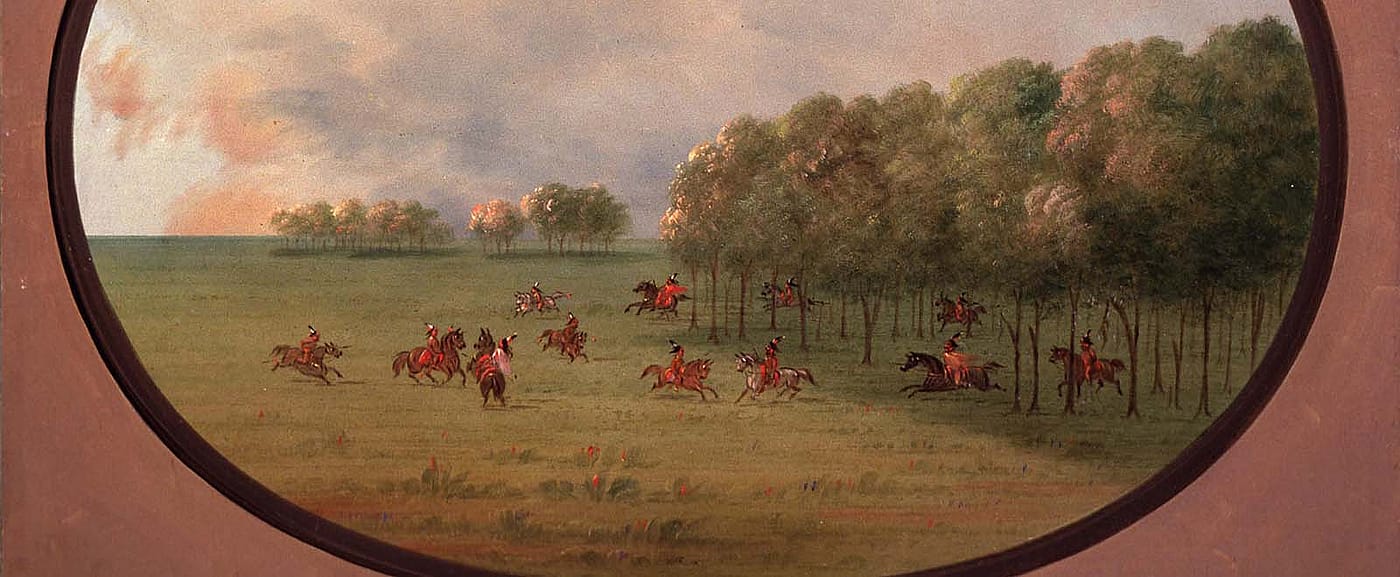

Around 1650, the Comanche, nomadic hunters of the northern Rocky Mountains, acquired horses from the Utes to the south. They quickly incorporated horses into their economies by moving south to the Plains to follow the bison and raid for more horses. Within 50 years the Comanches were known as the Lords of the Plains, dominating both Spanish settlements and other tribes who ventured into their lands in present-day New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and northern Mexico.

Horses spread to the tribes through trade and raiding reaching present-day western Canada by 1750. The Comanche began trading horses with Euro-American and other horse traders in the 1700s and continued until the 1870s.

Early, they adapted Spanish or Mexico style saddles, bits and other riding equipment. Women rode high-pommel saddles when moving camp and traveling. For buffalo hunting and warfare, Comanche men rode pad saddles made from buffalo hide stuffed with animal hair. These saddles were easier to dismount quickly than the high-pommel saddles. Stirrups were copied from Spanish-style platform stirrups made of carved or bent wood covered with rawhide. By the 1880s, Comanche men and women were riding their horses with U.S. Army bits and stock saddles.

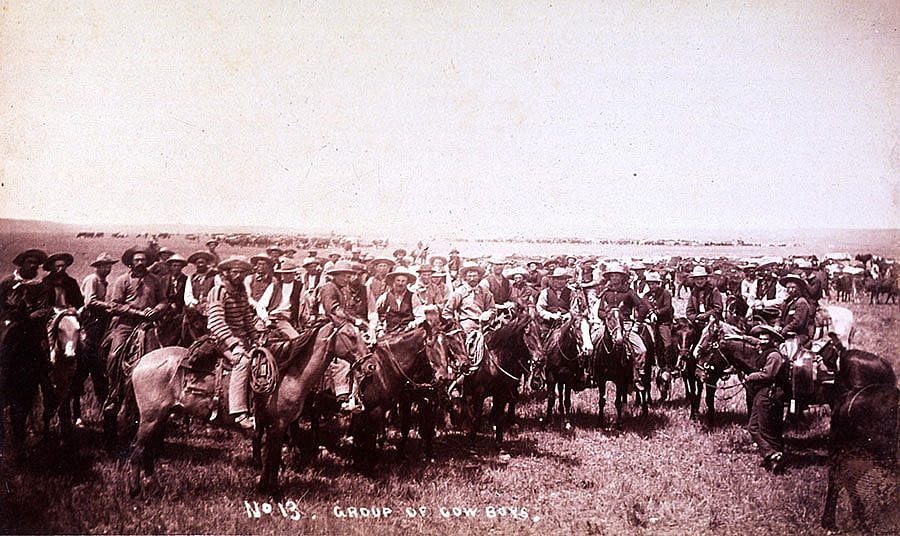

The Cowboys

The emphasis of Thundering Hooves is on the cowboys and ranches of Texas and the Southwest. The end of the Civil War initiated an era dominated by the cattle industry and the American cowboy. However, this era of growth lasted only about 20 years, ending within a decade after the decline of the Comanche and other buffalo-hunting tribes of the Plains.

Before the Civil War, ranches in the Southwest carried on the traditions of the Spanish ranches, with cowboys living with their families on a spread owned and operated by one person or a family. After the Civil War, enormous company-style ranches were established which were managed by foremen, but often owned by individuals from the East Coast or Europe.

Trail drives were an important part of the cattle trade, with the first official ride occurring in 1879, when more than 2,000 head of cattle were moved from present San Antonio, Texas to New Orleans. From the end of the Civil War to the mid-1880s the cattle market boomed, with over 10 million heads of Texas cattle moved north to Kansas.

Thundering Hooves contrasts the realities and myths of the West which were brought to wider audiences by the pulp novels of the 1870s and 1880s, theaters, and Wild West shows. Through the later development of mass media, stories of the West have become a part of a national lore.

Through more than 400 objects and videos, the exhibition weaves the story of the horse and the people of the West. Opening October 1, 1994, the exhibition, its international tour and some of the related educational programming were assembled by The Witte Museum of San Antonio, Texas, and made possible by the Ford Motor Company.

Post 013

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.