Thomas Moran and His Chromolithographs: Yellowstone in art – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2011

Thomas Moran and His Chromolithographs: Manifest Destiny in the Landscape of the West

By Christine C. Brindza

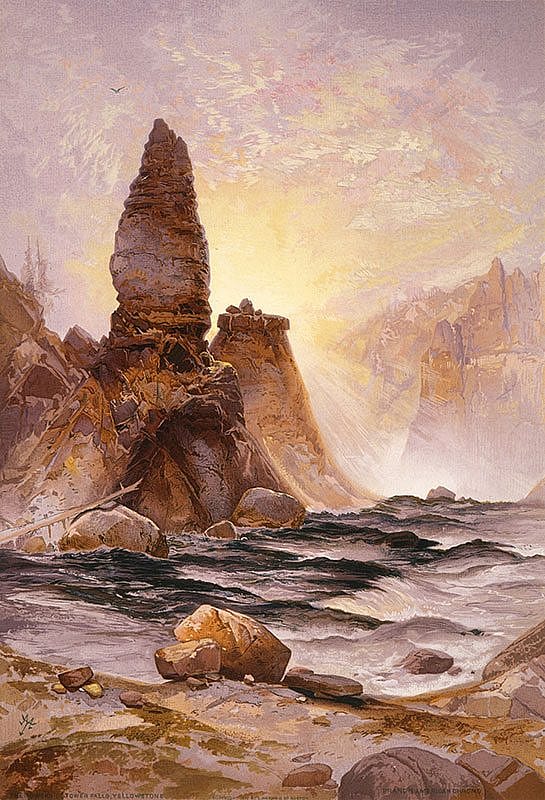

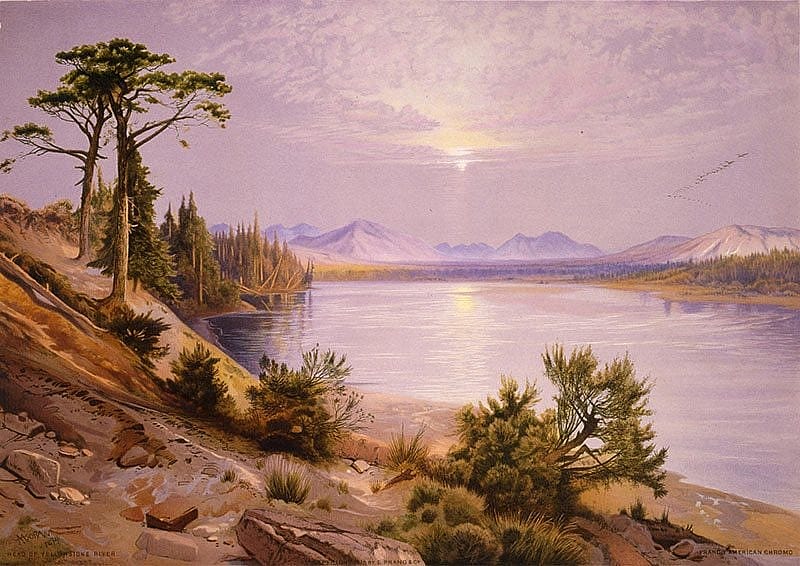

Unless otherwise noted, all Thomas Moran prints pictured here (ca. 1875) were generously donated to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West by Clara S. Peck in 1971, and all W.H. Jackson photographs (1871 Hayden Survey) are from the National Park Service.

The essence of American landscape painting, particularly scenes of the romantic and majestic West, is found in the art of Thomas Moran (1837 – 1926). Through his images of Yellowstone, Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, the Rocky Mountains, and various sites in between, the public had the opportunity to view places previously only imagined. By means of print media, Moran brought powerful grand vistas into homes across America in the latter nineteenth century.

In 1871, when the young Moran, an illustrator with Scribner’s Monthly magazine, was asked to join Ferdinand V. Hayden on a scientific expedition through the West, that would concentrate on the area known as Yellowstone, he eagerly accepted. Even before the trek, though, he had already illustrated his first Yellowstone image for his employer, although Moran had never seen it for himself, nor did he have clear and documented images from which to work.

At that time, in fact, there were only amateur drawings in existence of Yellowstone scenes. Moran’s given task was to enhance the field studies so they were presentable to larger audiences. This resulted in a set of wood engravings for an article titled “The Wonders of the Yellowstone” that appeared in the May and June 1871 editions of Scribner’s. It is little “wonder,” then, that after this, Moran’s great desire was to see Yellowstone and convey it accurately in his work.

After the historic journey with Hayden’s Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories in 1871, Moran went back to his studio and began creating masterpieces of great western lands, works that remain unsurpassed. At the time, though, he may not have been aware of the impact his accompaniment of the expedition would have on himself as an individual, the country, or the world. Nor did Moran likely consider how his work would come to influence public perceptions of the West. Still today, whether in painting or print form, his western scenes have a prominent place in American history and art.

Destiny manifest

One of Moran’s artistic approaches, capturing landscapes on large canvases, captivated audiences on a grand scale and inspired the creation of the world’s first national park: Yellowstone. His The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1872, with its vibrant colors, powerful geological formations, and fantastical viewpoints awed and astounded viewers.

The luminosity evident in Moran’s oeuvre—the hues of a sunset, a softly backlit environmental formation, or shimmering waters upon a lake—convey a feeling of wonder and admiration that many could attribute to a higher power. In her book Thomas Moran’s West: Chromolithography, High Art, and Popular Taste, author Joni L. Kinsey suggests that Moran’s landscapes convey a spiritual connection with the environment—an ideal, fertile, bounteous place blessed by God. In a sense, Moran’s hand conveyed the quintessence of Manifest Destiny.

An instrumental concept in the nineteenth century, Manifest Destiny suggested that there was a divine mission that drove the nation westward. The mid-continent—particularly those lands west of the Mississippi River acquired from France in the early 1800s—was still sparsely populated, though inhabited by Plains Indian tribes, small pioneer settlements, mountain men, and others. Most people who lived in the eastern part of the United States did not know what unique features could be found throughout those lands; many thought it to be full of magic and wonder or danger and peril—based on the tales they heard.

Writing in Frederic Church, Winslow Homer, and Thomas Moran: Tourism and the American Landscape, Dr. Karal Ann Marling observed that during the post American Civil War period, the West was a source of national pride and brought a fresh start to the war-torn country. The country needed to come together around something “uniquely American”—a quality evident in the land of the West. It was like no other place on the planet, and many Americans felt they had ownership of it.

Sharing the vistas

Though The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone was an absolute sensation upon its debut, not everyone could view Moran’s grand landscape painting or his other western scenes. Very few could afford to buy one of the paintings, and the number of audiences who were able to visit an exhibition was limited. However, Moran painted watercolors based on his western experience that were just as spectacular as the large canvases, but more intimate. To reach diverse populations on a smaller scale, it was logical to reproduce some of the watercolors in print form, particularly chromolithographs.

“Chromo” is from a Greek word for color, and the origin of the word “lithography” means “stone writing.” Lithography was a print technique employed by publishers producing advertisements, magazines, and other illustrated media since its invention around 1798. Used in America as early as the 1840s, chromolithography was a revolutionary print method that reproduced images in color.

The chromolithography procedure begins with a smooth stone or plate. It is a planographic or “flat” process in which an image is drawn on the stone with grease-based medium, and then the stone is wetted by water. Since water and grease repel, the parts of the image without the grease are saturated, and the parts with the medium applied are undisturbed. The idea is that when the ink is applied, it only adheres to the image.

Paper is then carefully placed on the stone and pressed, and then the ink lifts onto the paper. In chromolithography, individual colors are applied one at a time, using one stone at a time—a tedious and expensive process. It required a very skilled worker, called a chromiste, to model the original image onto the stone. Transfer paper was often used to exactly reproduce the image from one stone to another. The more exact an image, the better quality the print, according to Kinsey.

Because he was employed as an illustrator, Moran was exposed to printing processes. Earlier in his life, starting in 1853, he served as an apprentice in a print shop, a position he held for three years. His brothers Edward and Peter were also trained lithographers. When he was hired to work on a series of chromolithographs for Louis Prang, Moran likely understood what kind of image could be reproduced well, the painstaking process involved, and the power of public visibility that printed matter attained. More viewers would be able to see a print in a magazine than the actual painting on display.

An extraordinary portfolio

Publisher Louis Prang of L. Prang & Co. believed that art should not be viewed or owned only by the elite and thought that chromolithography was the best way to present images of fine art to the general public. He had been producing chromolithographs since the 1860s along with greeting cards and advertisements. He worked with Moran in the mid-1870s to create The Yellowstone National Park, and the Mountain Regions of Portions of Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah. The portfolio, published in 1876, was primarily designed by Moran and had accompanying text written by Hayden. Moran originally submitted twenty-four images, but the publication used only fifteen.

In the Prang publication, Moran’s watercolors were converted into chromolithographs and took on a new existence. They appeared much bolder and more vibrant than Moran’s originals due to the print process. The Great Blue Spring of the Lower Geyser Basin, for example, features a once very active geyser now called Excelsior Geyser Crater. This natural site lent itself to dramatic color, which Moran captured in his representation. The vivid deep blues, reds, and rusts portray the magnificent display of the geyser and its water runoff into the Firehole River. The mineral deposits from this overflow leave swirls of color which lead the eye from the background to the foreground.

Moran was quite taken by the blue spring when he saw it in 1871 and created a watercolor field sketch of the scene which he referenced later. (He recreated this image again in several watercolors, one of which is in the Whitney Gallery of Western Art collection.) In The Yellowstone National Park, Hayden wrote of the scene, “…It is almost impossible to give an idea either in words or picture of the exquisite beauty of the springs of which the Great Blue Spring is a type.” Though Hayden did not think it possible to replicate this scene, Moran’s endeavor met with remarkable success.

Mountain of Holy Cross

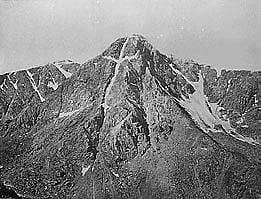

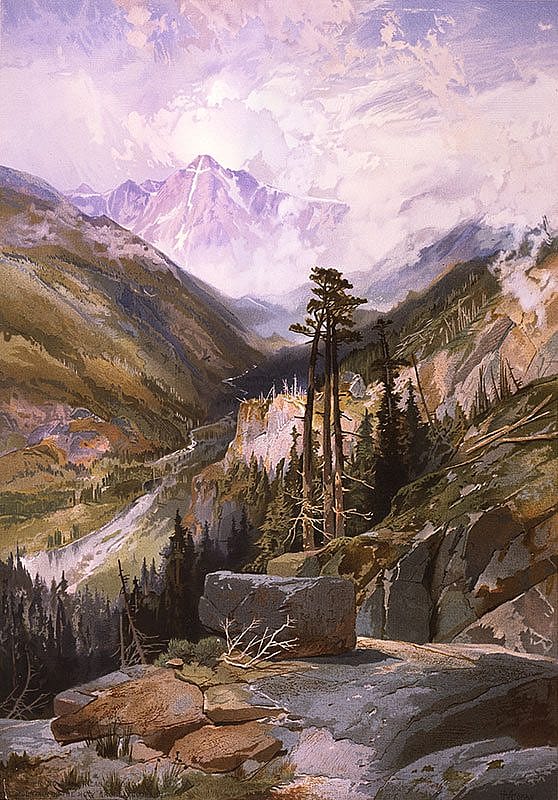

Moran painted Mountain of the Holy Cross, an idealized interpretation based on an actual mountain located in Colorado. After viewing a photograph of the mountain by William Henry Jackson, a friend and fellow explorer on the Hayden Survey in 1871, Moran’s fascination with the site inspired him to paint it. Jackson accompanied Hayden in 1873 and captured the distinct cross-shaped snow formation on film along with other scenes of the Rocky Mountains.

Moran visited the mountain himself the next summer and completed the painting of Mountain of the Holy Cross in 1875. It became the prime attraction at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the following year. Visitors were able to examine the photograph and painting together, both of which represented what authors William H. and William N. Goetzmann describe as “…the pinnacle of America’s fascination with the Rocky Mountains as manifestations of the romantic sublime.”

Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was one of thousands who viewed Moran’s painting. Later he wrote a poem about it, mourning the loss of his wife. The excerpt below is from his A Cross of Snow:

There is a mountain in the distant West

That, sun-defying, in its deep ravines

Displays a cross of snow upon its side.

Such is the cross I wear upon my breast

These eighteen years, through all the changing scenes

And seasons, changeless since the day she died.

The United States, traditionally considered a Christian nation, took Holy Cross as an archetypal image they could apply to the struggle of their country in the post-Civil War period: The burden of the cross marked America itself. Once again, people viewed Moran as a master painter for his portrayal of the West. He included Holy Cross in the Prang series of chromolithographs, incorporating the luminous color and drama prevalent in his original painting.

Moran and the West

Moran’s The Valley of the Babbling Waters chromolithograph depicts today’s Zion National Park in southern Utah. In 1873, while Hayden and Jackson saw the Mountain of the Holy Cross, Moran was on another expedition, this time led by John Wesley Powell. Moran saw and depicted the Virgin River and steep Zion Canyon—particularly featuring Angel’s Landing. Moran’s rendition of Zion is not an exact view, but a compilation of beautiful perspectives found in the area. He worked from sketches he created during the Powell Survey, and it is evident that the artist was compelled to capture the characteristic colors of the canyon walls.

During his lifetime, Moran accompanied three geological surveys of the West, with either Hayden or Powell as leader. He learned a great deal from the scientists who were part of the expeditions and applied this knowledge to his art. Moran came to understand how the earth was constantly evolving and that there were geological forces at hand that created the formations he saw before him. Further evidence of this is found in how he would often describe places in geological terms in his personal notes, even after the survey was completed. His image of Babbling Waters demonstrates how he used his appreciation and recognition of geological creations.

Moran’s chromolithographs covered many scenes across Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, and, of course, Yellowstone, located in the northwest corner of Wyoming. Most of the chromolithographs featured a part of Yellowstone, including a print version of the famous Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, along with Castle Geyser, Yellowstone Lake (of which he composed several different scenes), and others.

Typically, Moran worked from sketches and photographs, as in the case of Yellowstone Lake where the painting was based on a real viewing position, Promontory Point, located on the southern arm of the lake. While on the 1871 Hayden Survey, Moran made several drawings as William Henry Jackson photographed the lake. He incorporated a perfect rainbow arched across the water—perhaps a symbol of new life in the “promised land” of the West or a reminder of the rainbow that appeared after the great flood recorded in the Biblical text of Genesis, according to Kinsey.

Chromolithographs for sale

Moran thought that published art was a mode of creative expression that should be viewed with no less enthusiasm than “original” work, and he made particular efforts in the creation of his chromolithographs. His scenes of far-away lands could be brought into homes and enjoyed by a close captive audience. However, due to the time and skill required, the prints had to be sold at higher prices than most people could afford. The original publication was sold at $60 a copy, which converts to about $1,000 today.

The chromolithograph series started with a run of a thousand copies. Only 10 percent of those produced were sold or given away. Prang hoped that the influence of Hayden, as well as the survey’s position as part of the federal government, would help boost sales. L. Prang & Co. sent copies to politicians in hopes that their interest would spark more purchases. The company sought endorsements from many noteworthy persons, including President Ulysses S. Grant and Queen Victoria of England, but only a few wrote endorsements for the series. Queen Victoria did not give her endorsement, but did enjoy the illustrations and deposited the book in her Royal Library.

Most of the remaining inventory from the press run was destroyed in a fire in 1877, along with many of the plates. The portfolio became a rarity in its own time, and today has significant aesthetic and monetary worth.

Epilogue

In her book, Kinsey says that Moran was “…very mindful that printed images disseminated his vision to a wide public and raised awareness of an interest in the vast reaches of American landscape.” He also was conscious of the power messages from the West provided in the late nineteenth century. The idea of Manifest Destiny and spiritual fulfillment revealed by the West coincided with Moran’s own destiny to paint the ideal and romantic western landscape.

Upon Moran’s death in 1926, the director of the National Park Service, Stephen Mather, remarked, “…he more than any other artist has made us acquainted with the Great West.” Moran brought to light how both paintings and print media could depict the grandiose landscapes he once considered “…beyond the reach of human art.” Using technology of the day and crossing into multiple artistic disciplines and scales, Moran was able to reach more audiences and convey idealized versions of the West. He incorporated authentic geological forms, but added his own imaginative spin—sometimes with religious connotations. He embraced some of the standards of Manifest Destiny, intertwining it with his own artistic destiny and his role in shaping the attitudes of the public about what lay west of the Mississippi.

About the author

At the time this article was published in Points West, Christine C. Brindza was serving as Acting Curator of the Whitney Gallery of Western Art. Along with the exhibition The West of Thomas Moran, she also curated the exhibits Curator’s Choice: The Art of Frederic Remington and Brush, Palette, and Custer’s Last Stand. She has a Master of Arts degree in Archival, Museum, and Editing Studies, and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Art History from Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- The West of Thomas Moran, featuring this famous series of Moran chromolithographs was on view at the time this article was written. The McCracken Research Library is fortunate to have a Prang portfolio.

- For further reading: Joni Kinsey’s Thomas Moran’s West: Chromolithography, High Art, and Popular Taste and Frederic Church, Winslow Homer, and Thomas Moran: Tourism and the American Landscape by Dr. Karal Ann Marling.

- Great Blue Spring of the Lower Geyser Basin is available as a print from our Museum Store; call 1-800-533-3838 to purchase yours today.

- This collection brought to you by a donor—thank you!

Post 015

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.