James Bama: Choosing Cody, Attaining Art – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2003

James Bama: Choosing Cody, Attaining Art

By Sarah E. Boehme

Former Curator, Whitney Western Art Museum

For artist James Bama, the decision to move to the Cody, Wyoming, region played a pivotal role in his career. Wyoming affected the subjects he portrays—the people of the West and the ideas of what the West means—but the region’s significance is greater than subject matter. Moving westward has often symbolized a break with the past, a seeking of freedom from restrictions, and a desire to chart one’s own course. For Bama, the decision to live in the West was one linked inextricably to pursuing his own artistic freedom and to producing a major body of creative work.

The urban environment of New York City nurtured the artist in his formative years. Born in Washington Heights, Manhattan, in 1926, Bama grew up during the Depression.(1) The available visual resources, primarily newspaper comic strips with storylines and strong graphics such as Flash Gordon and Tarzan, inspired his early artistic aptitude. He graduated from the prestigious High School of Music and Art in New York City in 1944 as World War II raged on. Bama served in the U.S. Army Air Corps for seventeen months, then enrolled in the Art Students League of New York. He studied there from 1945 – 49, primarily with Frank J. Reilly, a respected illustrator and teacher.

In the post-War years, as the nation rebounded from the strictures of the war economy and as the art scene exploded with the audacities of expressionism, Bama chose to study realistic representation, a path that had practical possibilities and also suited his esthetic predilections. Under Reilly’s tutelage, he concentrated on the fundamentals of art, with a strong emphasis on form, human anatomy, and careful craftsmanship. According to Bama, Reilly had an almost scientific approach to painting and his methodology emphasized theories of light and shade.

Bama’s training honed skills that were constructive for illustrational work, and he developed a successful career providing visual imagery to accompany a wide range of materials and subjects. He worked as a freelance artist, then for Charles E. Cooper Studios from 1950 until 1966, then again as a freelancer. While working in the Cooper Studios, Bama became friends with fellow artist Robert William Meyers (1919 – 1970), who would later have an important influence on Bama’s artistic direction. In this period he produced advertising images for major accounts including General Electric and Coca-Cola and illustrations for popular magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post and Reader’s Digest were mainstays.

Bama’s own interest in sports found outlets in paintings for the Baseball and Football Halls of Fame, and as official artist for the New York Giants football team. He designed movie posters and did the original art work for television series, including Bonanza and Star Trek. Fans of the pulp adventure series, Doc Savage, relish the memorable book covers Bama produced for Bantam Books in the 1960s. Bama’s background and training certainly contributed to his success in portraying Doc Savage, the urban superhero who emerged from his headquarters in a Manhattan skyscraper to fight evil around the world. The artist used his knowledge of anatomy, but as was appropriate for the story and setting, he heightened and exaggerated elements to create a super-reality. The covers featured a strong, dominant figure and bold color palettes to draw the eye to the Man of Bronze.

Illustrational work provided steady and reliable income, but the strictures of formula and tight production time limited Bama’s possibilities for creativity. His marriage in 1964 to Lynne Klepfer, a graduate of New York University with an art history major, actually served to give confidence to the artist to break from commercial work. In contrast to the conventional wisdom that marriage results in less risk-taking and more practicality, for James Bama it meant new freedom. Lynne Bama, a photographer and writer, encouraged her husband to paint his vision rather than follow the directives of the market.

The couple also sought together an environment that would allow them to pursue their work, and that meant breaking from urban distractions and commercial settings. Although he had a youthful enthusiasm for the romantic idea of the West, James Bama did not start with a passion for the region, like the one that propelled artists such as C.M. Russell or J.H. Sharp; he first considered moving to New England. His primary artistic inspirations were not the western artists, but rather, Norman Rockwell, Dean Cornwell, Andrew Wyeth, and Frank Leyendecker, artists noted for effective illustrations, realistic styles, and strong compositions.

What brought Bama to Cody Country was the desire to see a new environment, but one that had a link in friendship. In June 1966, the Bamas made a momentous trip. They came to visit friend and fellow artist Robert William Meyers at his ranch, the Circle M, on the Southfork of the Shoshone River, outside of Cody, Wyoming. Bob Meyers had left New York and his successful career as an illustrator for publications such as The Saturday Evening Post and True to move west to paint and operate a ranch.(2) The Bamas found a beautiful landscape, which they explored on horseback, and they also experienced the peace and solitude that seemed so promising for concentration. They returned for visits in May and June 1967, and then moved from the heart of Manhattan to a cabin on the Meyers’ ranch in September 1968.

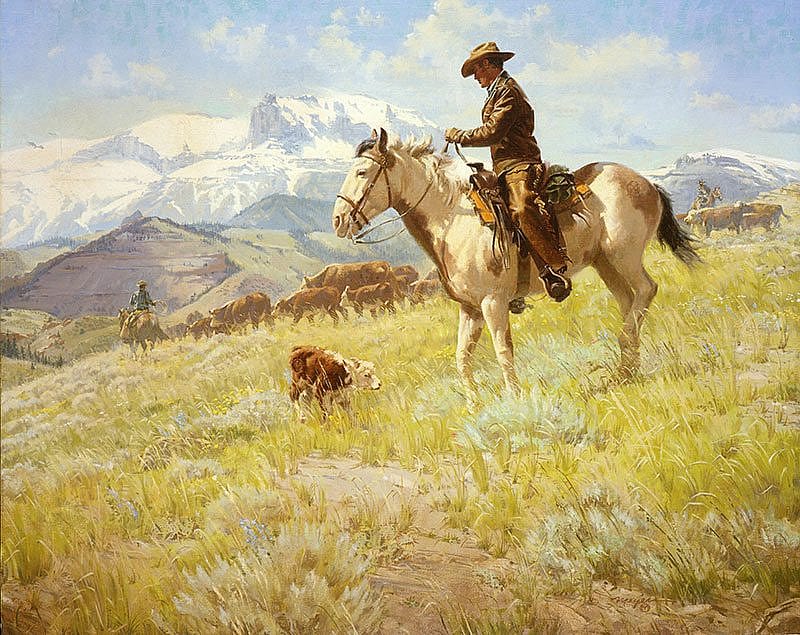

Although Bama continued illustrational work for the first couple of years, the move signaled a major change as he sought to paint works of art that expressed his artistic concerns. In those first years, he painted for himself in the day and did illustrating at night. He found inspiring subjects in this corner of Wyoming. The West had often attracted artists like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran who wanted to depict the natural beauty of the landscape. Others, like Frederic Remington and C.M. Russell, found inspiration in the human narratives and drama of the West.

Similar to those artists, Bama gravitated to the people of the West, but as individuals rather than as elements in an action-packed story. The category that defines his subject is portraiture, which may seem an ironic specialization. As illustration work has been regarded as limiting, portraiture too has often been viewed as restrictive to the artist, because portraits are frequently done to meet the needs of an individual client for personal commemoration. Bama’s paintings, however, portray individuals whose visual appeal goes far beyond the interests of their immediate family or business circle. From his base in the Cody Country area, he had access to a wide range of subjects, and in depicting his western subjects he created images that resonate with significance. In Cody he found older men and women whose lives encompassed the region’s history. At rodeos and powwows, he met people who maintained connections with the past.

Bama moved from the Southfork to the Northfork of the Shoshone River in 1971. He and Lynne found a house on Dunn Creek, Wapiti, about 20 miles outside Cody. Bob Meyers had been tragically murdered in 1970 and his widow Helen moved from the ranch. By May 1971, Bama had produced enough paintings to secure representation with a New York dealer, and by that July he had made the decision to abandon illustration and devote himself full-time to easel painting. In 1978 their son Ben was born and they then moved into the Wapiti house that they had built as home and studio.

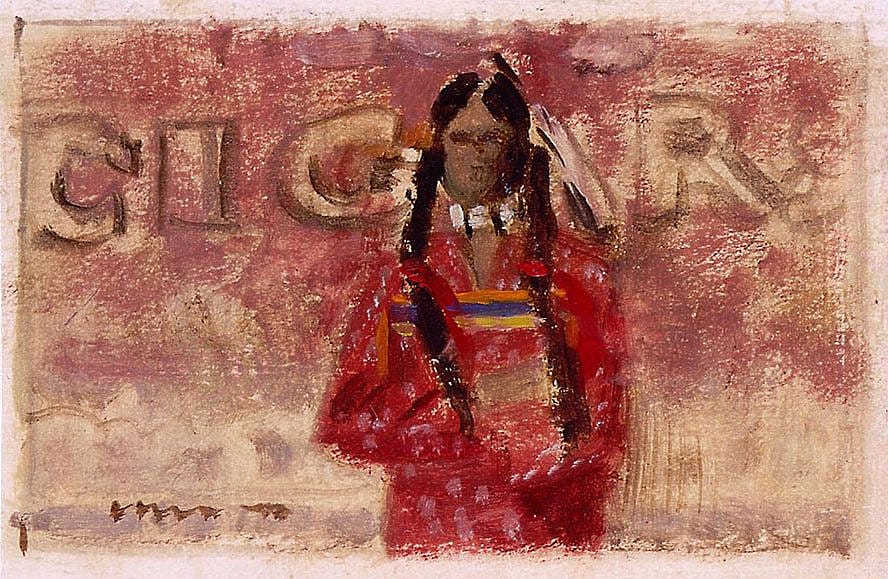

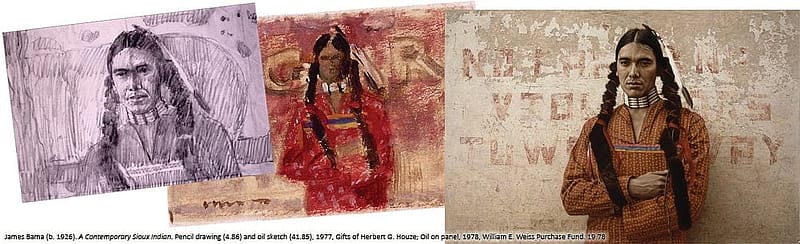

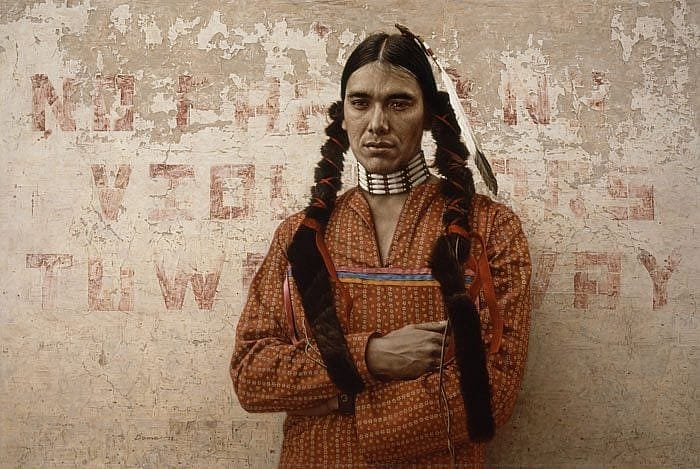

Bama concentrates on contemporary figures of the American West. He portrays real people who often have complex reactions to their place in the West. His painting A Contemporary Sioux Indian is one of his most masterful statements. He portrays a young Oglala Sioux, Wendy Irving, leaning against a wall, with peeling paint, but with the still evident message “NO PARKING VIOLATORS TOWED AWAY.” In this work Bama deals with issues of Indian roles in contemporary society. The young Sioux wears braids, a feather and choker, identifiers with traditional ways. His ribbon shirt, still traditional but more contemporary, signals the changes made by contact. The wall and its message provide the sense of dislocation. Bama made the decision to depict the figure against a flat background so the figure would stand out, and for the series of Indians he chose concrete walls that would seem like a flat tapestry behind the figure. Bama described the painting as a statement about young Indians today who “are not welcome unless they conform to white man’s ways.”(3)

Bama’s painting style, an intense realism, draws the viewer to his works. His technical skills astonish. The convincing representation of three dimensions in two dimensions and the masterful depiction of material textures attract the eye, and then engage the viewer in contemplation. Photography is a crucial tool for his painting process, and over the years Bama has amassed an archive of hundreds of photographic negatives and prints of western figures. The photograph, however, is only one step toward the finished work. From the photograph, he will prepare pencil studies, usually on a transparent paper, to work out a pose and to guide his modeling of the figure. Then, he makes small color studies to establish the palette. He often paints on board, such as masonite prepared with gesso, for a smooth surface. Bama draws a pencil sketch, then puts a tonal color on the board, then redraws the figure with oils and paints in thin layers. Bama’s smooth surfaces leave little evidence of the painter’s brushstrokes, heightening the verisimilitude.

The West gave James Bama the freedom to produce his body of work, and it also provided a venue where realism could flourish. Outside the urban centers where the intense stylistic upheavals reign, the realistic approach to painting remains valued and respected. Earlier in his career, it was necessary to return to New York to have an outlet for his paintings. Now an art gallery based in Cody, Wyoming, but one that can reach international clients, exclusively represents his work. Bama has said that Cody “freed me to do the things that I really believe I was meant to do.”(4) In Cody Country, Bama found the environment that excited his imagination and that allowed him to flourish and to create an important artistic legacy.

1. The most comprehensive publication on the artist is The Art of James Bama, text by Elmer Kelton, (Trumbull, Connecticut: The Greenwich Workshop, 1993).

2. For Meyers, see entry in Harold and Peggy Samuels, The Illustrated Biographical Encyclopedia of Artists of the American West, (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1976).

3. James Bama, answers to questionnaire, 1989, Whitney Gallery of Western Art files.

4. Telephone interview with the author, 2003.

Post 016

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.