Alchemists of Cody, firearms engraving – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2003

Alchemists of Cody, firearms engraving

What if we could find a way to turn drab, ordinary metal into glittering, precious gold? It was a challenging question and an exciting idea! It captured the imagination of many of the chemists of the Middle Ages and determined the use of much of their time and energies. Those who dedicated themselves entirely to this dream of miraculous transformation were called alchemists. If they could find a way to work their magic, and keep it a closely-guarded secret, how very wealthy and powerful they and their sponsors would become!

We now know, of course, that the hope of such dramatic transmutation was never actualized. The alchemists failed to make their dream come true, so they came to be regarded as proponents of a delusion. Their lofty obsession gradually lost its allure, and chemists pursued other, more promising projects. History would assign alchemy to the dusty storage bins of the quaint and the trivial.

The alchemists of the Middle Ages provide us, however, with an insightful contemporary metaphor. People who transform the commonplace into the extraordinary, the plain into the beautiful, the merely functional into the splendid and inspiring might well be considered to be alchemists. Those capable of such remarkable changes can, at least figuratively, make the ancient dream come true. With their skills, patience and dedication they truly alter ordinary objects into creative works of beauty and significance. Beneath their eyes and hands the lead and iron of craftsmanship become the gold and platinum of fine artistry.

They are part of an ancient tradition. As early as the 16th century, around five hundred years ago, owners of primitive firearms, for example, wanted them to be aesthetically pleasing and attractive. Their guns were designed and produced as tools of survival. They were intended to provide meat for the table, or protection against animal attack, or defense for self and family against hostile human aggression. Those who used them wanted them to be even more. They wanted them to be sources of enjoyment and pride of ownership. They wanted them decorated and embellished—beautiful as well as functional.

So privately-owned firearms, more so than military weapons, began to be changed from the mundane into the spectacular. The plain metal barrels and lockplates and hammers and trigger guards were engraved with lovely scroll-work patterns featuring vines and flowers, portraits of animals, people, landscapes and beings from mythology. The images were embellished by being damascened or inlaid with gold and silver. The woods of stocks and grips were also often carved and enhanced with pieces of ivory, mother-of-pearl, stag horn, tortoiseshell and exotic woods.

By the late 16th and early 17th centuries cumbersome matchlock firearms were being displaced by smaller, more sophisticated guns called wheel locks. They had greater appeal to the better educated, and more affluent, members of the upper classes of society. These new owners liked, and could more readily afford, highly embellished firearms, so the practice of engraving became widespread. The craftsmen of northern Italy, and of Brescia in particular, acquired a reputation for excellence. Fine work was also done in Germany and France. Soon even prominent artists were being commissioned to create designs and sketches to be transferred to the metal surfaces of the wheel locks by engravers. Many of the resultant scenes were miniature masterpieces of technical artistry.

Hand engraving by a skilled artisan was the most desired and treasured. It was done by placing the appropriate parts in a vise and incising patterned lines into the metals with a small hammer and a sharp-pointed tool known as a burin. This style of chiseling was difficult, time-consuming work requiring patience, considerable skill and a highly developed sense of symmetry and balance. Early engravers were quite secretive about their work, passing along their designs and techniques only to carefully selected apprentices who had to practice for several years before being permitted to put out their own creations. Across the years high quality engraving came to be regarded as the pinnacle accomplishment in the world of gun making. It was the feature that elevated a firearm from the category of a fine product into the sphere of fine art. In the mass production of firearms apparent engraving was, in fact, stamped on the metals with dies. It has never been comparable to the work done by skilled engravers like Young, Nimschke, Kornbrath, and the Ulrichs, to name but a few of the best.

Engraving was for a time considered to be a dying art. By 2002 there were only 330 members of the American Engravers Guild. But the demand for high quality engraving as an element in the embellishment of firearms remains as high as ever, and, fortunately, there seems to be a resurgence of interest in the craft. Perhaps even more significantly, there are still those in our midst who have the ability to transform craftsmanship into artistry. Among the reasons that Cody can be considered to be a center for the arts today is that, in addition to its painters and sculptors, there are several highly competent engravers and knifemakers among its residents. They are the Alchemists of Cody. Let me introduce you to some of them.

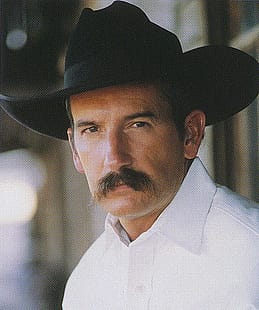

Ernie Lytle operates E. A. Lytle engraving from a compact shop amid the splendor of the North Fork of the Shoshone River. A native of North Carolina, Ernie came to Cody ten years ago by way of Texas, New Mexico and California. His mobility was related to his work on a succession of ranches as a cutting horse trainer. Along the way he became a maker of bits and spurs, first as a hobby and then commercially. The problem was that he took ever-increasing amounts of time with each piece, trying to make it as functional and attractive as possible. He finally began to engrave them, learning many of the fundamentals of engraving on his own. By fifteen years ago he was completely committed to engraving as a vocation.

Once in Cody, Ernie had the privilege of working under the guidance of Joseph, a now retired Master Engraver for Winchester. That apprenticeship, coupled with his own serious study of the designs and techniques of Gustave Young and Louis D. Nimschke, resulted in a quantum leap in the quality of his work. His continuing goal is for each piece of work to be an improvement over the ones that preceded it. Evidence of the attainment of that goal is found in increasing depictions of his engraving in books and journals and in the striking images that accompany this article. Ernie still engraves watches and gold inlaid Ranger sets of belt buckles, tips and keepers for the Montana Watch Company of Livingston, as well as firearms. Regardless of the medium, his work reflects the commitment and the capabilities of a true artist.

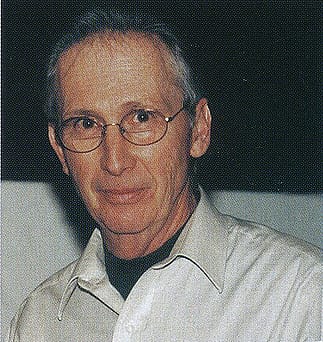

Another firearms engraver of note is Bill Johns who can be found daily at his shop on Cody’s West Strip. Bill manages somehow to intersperse interaction with a steady stream of customers with his engraving of firearms, knives and jewelry, as well as the design and creation of numerous other articles of silver and gold such as belt buckles, rings, gun grip inlays and saddle leather trim. He learned to engrave as a boy from an elderly German gunsmith. After serving in the U. S. Navy for four years during the Korean War, he came to Wyoming and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Wyoming. He has been an active engraver for over 40 years.

Bill is best known for his work on Colt single actions, Winchesters, and other guns of the old west. His work has been recognized and publicized world-wide. He engraved and gold inlaid the Colt revolvers that were presented to John Ford and Henry Hathaway at the completion of the filming of “How the West Was Won.” He also engraved the two derringers used in the movie “Maverick.” Movie and television stars regularly call on him to engrave their firearms. The images of his work with this article fully explain their reasons. Bill is a recognized and successful part of the artists’ community in Cody.

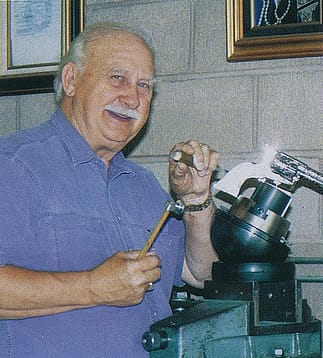

Many of the same technological and artistic skills employed in the engraving of firearms can be found in the efforts of “The Cody Cutler,” W.E. “Bill” Ankrom. Bill began his knifemaking career as a 32 year old toolmaker in Detroit. He went into the endeavor full time in 1979, moving to Cody the following year when he realized that as a knifemaker he could live anywhere he wanted to in the United States.

He has since become one of the top makers in the nation of what he calls “arty” folding knives. By “arty” Bill means the use of elephant and fossil ivory, mother-of-pearl and exotic wood handle scales; Damascus blades with intricate patterns; bolsters of mokume, titanium or mosaic Damascus; and engraving by people like Julie Warenski and Simon Lytton.

Bill speaks of himself as a performer of stock removal, in the same sense that a skilled sculptor chips away unwanted stone. He cuts, grinds and polishes until the remaining material assumes the precise shape and surface texture desired. Equally as important is the matching, blending and contrasting of the component materials of the knife to attain the most compatible and balanced composition possible, even as a painter brings together the colors and elements of a painting until it conveys the meaning and effect sought. So “arty” really means artistic, and these images support the concept better than words. Knifemaking is Bill Ankrom’s craft; fine art is his end result.

These three are an integral part of a Cody Colony of Artisans. There are others like them among Cody’s residents. They are alchemists, transforming the ordinary into the golden preciousness of high art. It is strongly suspected that history will deal with them much more kindly than with their progenitors in alchemy.

Post 023

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.