The Wolverine, Trickster Hero – Points West Online

From Points West magazine

Originally published in Winter 2011

The Trickster Hero

“For its size, the wolverine is probably one of the smallest and most powerful top-of-the-food-chain predators. It makes a Tasmanian Devil look like a sissy.” —the Chicago Wolverines Minor League Football Team, on Eteamz

By Philip and Susan McClinton

Ask anyone to describe a wolverine, and they’ll probably say it’s a character from the X-Men series, so popular with today’s movie goers.

Someone else might observe that the wolverine is the mascot for the University of Michigan, or note that the state of Michigan is known as the “Wolverine State.”

Certainly, that X-Men character does share some attributes with the real wolverine such as his great ferocity despite his small stature, and his highly individualistic and aggressive behavior—all very desirable characteristics in a superhero.

Pointing to the wolverine’s oily, dark fur, which is highly “hydrophobic,” (meaning that the coat repels water and frost), others will mention the hunters and trappers who lined their coats with wolverine fur. Still others are reminded that the United States Armed Forces used wolverine fur as the ruff around the hood of arctic parkas.

Finally, historians may point out that many Detroiters volunteered to fight during the American Civil War, and George Armstrong Custer, who led the Michigan Brigade, called them the “Wolverines.”

Yes, the mere mention of wolverines conjures up a wide variety of responses.

Mountain Devil

Native Americans called the wolverine “carcajou,” a French corruption of a Native American word meaning “evil spirit” or “mountain devil.” The wolverine is neither spirit nor devil, however.

The wolverine figures prominently in the mythology of the Innu people of eastern Québec and Labrador, and in at least one Innu myth, the wolverine is the creator of the world. Irene Benard, an Inupiat/Cree Native American, tells the tale of wolverine trying to steal the light from the midnight sky, and then blaming it on Raven Boy, who fashioned large snowballs of sun, moon, star dust, and snow, and tossed them into the midnight sky. The snowballs reflected the light and are said to have created the northern lights we see today.

Some Native Americans believed that wolverines possessed special powers and were the magical link between the spirit and material worlds. Wolverines were held as the last phantom of the wilderness, the master of the forest, and the trickster hero. Numerous wolverine traits were held sacred by Native Americans: fierceness, strength, cleverness, endurance, courage, and the ability to stand and hold its ground. All of these traits, plus some amazing physical characteristics, add to the allure of this quintessential“true wilderness” mammal.

King of the mustelids

The New World wolverine, Gulo gulo luscus (Gulo is Latin for “glutton”), is also variously called quickhatch, glutton, skunk bear, and nasty cat (referring to its pungent odor), and is the largest land-dwelling species of the family Mustelidae (weasels). There is a clear distinction between Old and New World wolverines, Gulo gulo gulo and G. gulo luscus, respectively, but current taxonomy supports either of the two continental subspecies, or more likely, G. gulo as a single Holarctic (northern parts of the Old and New Worlds) category.

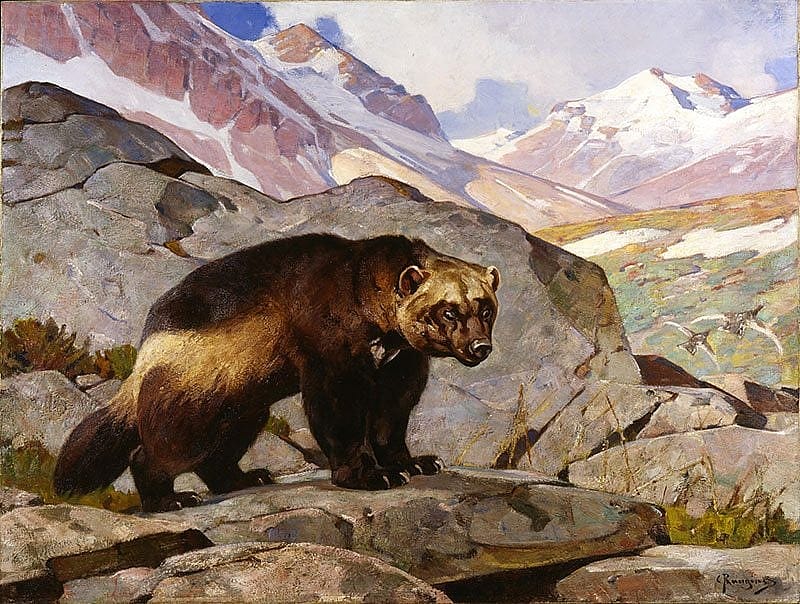

The wolverine is muscular, sturdy, and thickly built, with a round and broad head, short rounded ears, and small eyes. It resembles a bear more than a mustelid. Wolverines have short legs and move via plantigrade locomotion like humans, i.e. sole-to-ground. This trait and large paws enable it to move through deep snow with little effort.

Writing about wolverines in the Greater Yellowstone region, research biologists from the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Wyoming Game and Fish Department, noted in their final report, titled Wolverine Conservation in Yellowstone National Park (March 2011), that the pelage on wolverines is glossy, dark, and thick, with side stripes ranging from faint to prominent. These wolverines also exhibited yellow to cream chest and throat patches. Although not mentioned in the report, some wolverines even have white hair on their forelegs, paws, and toes, and some have distinctive silvery facial masks, and for all, a long bushy tail completes this mammal’s ensemble.

The wolverine has thirty-eight teeth and, like other mustelids, possesses a special upper molar in the back of the mouth that is rotated ninety degrees toward the inside of the mouth. This tooth allows it to tear off meat from prey or carrion that has been frozen solid. One can only guess at the jaw strength that allows wolverines to accomplish this daunting task!

Wolverines have a reputation for ferocity and strength disproportionate to their size, with the documented ability to kill prey many times larger. They are both scavenger and predator, and will challenge wolves, mountain lions, and even bears for carrion and/or kills. A wolverine can drag an animal three times its own weight for some distance, a feat surely made more complicated by its surroundings in alpine forests. Adult wolverines are about the size of a medium dog, weighing an average 26 – 42 pounds, and males are as much as 30 percent larger than females.

The wolverine averages thirty-six inches in length—a full yard of snarling fury when caught in traps. As with all species, there is physical variation with some built low to the ground, and others with long, rangy legs. Of the mustelids, only the marine-dwelling sea otter and giant otter of the Amazon basin are larger than the terrestrial wolverine.

Successful males will form lifetime relationships with two or three females which they will visit occasionally, while other males are left without a mate. Females exhibit delayed implantation of the embryo, and kits are usually born in the spring, but while there is still snow on the ground. Litters of two or three kits quickly develop, reaching adult size the first year. Kits are born white to blend in with the snow.

Lifespan for wolverines is usually between five and thirteen years. Fathers participate in early nurturing of the kits who may even join their fathers as travel companions for a time. Wolverines are very good parents and can demonstrate some remarkably human attributes as Doug Chadwick writes in his book, The Wolverine Way (2010, Patagonia Books). Chadwick talks of following a female wolverine to her den, and then:

“…we blocked the entrance and started digging on all sides. The mother must have felt cornered because she came bursting right up through the snow like a Titan missile from a submarine…” Two tiny female kits were fitted with transmitters for tracking, but one kit ” …cried and cried…” after the operation. The kit later died. Chadwick noted that he “…found the kit’s body later in a small depression scraped into the ground. Pieces of wood had been chewed off a log and laid over her. It was almost certainly the work of the mother, and she hadn’t disturbed the site since…that little grave was unbearable.”

Skunk bear

Wolverines, like many mustelids, have strong anal scent glands which aid in sexual signaling and marking territory. This pungent, high potency smell accounts for its nickname “skunk bear” by the Blackfeet Indians and“nasty cat.” Anecdotally, old timers in Alaska tell tales of wolverines following traplines to cabins, and then spraying the cabins and meat caches with the offensive odor, rendering them unusable. Wolverines don’t use their scent as a defensive mechanism, though. On the contrary, a wolverine typically drives other animals away from food by baring its teeth, raising its “hackles”(the hair on its back), sticking up its bushy tail, and emitting a low growl.

With almost two-inch claws, wolverines can be quite formidable, using their teeth and claws to attack would-be opponents. Still, they are not quite the “mountain devils” they are made out to be. Chadwick tells of his experiences wandering with what he calls a “gang” of penned wolverines, saying:

“…they were ambling and loping about, clambering on the logs and branches like stocky monkeys or giant flesh-eating squirrels…one lazed on its back with its legs in the air, baby bear style.”

From Chadwick’s description, these mammals weren’t the ferocious fearless creature of lore, but still very wild—albeit penned—wolverines!

Yes, the wolverine is noted for its fearlessness, strength, voracity, and cunning. It is a solitary, nocturnal hunter, and whether eating live prey or carrion, the wolverine’s feeding style appears voracious, giving it the nickname “glutton” (also the basis of the scientific name)—an understandable adaptation to scarce food sources, especially in the winter. In the Greater Yellowstone region, wolverines prey on mountain goat and elk, but other food sources may include mice, voles, marmot, moose, mule deer, and white-tailed deer, to name just a few. Wolverines pursue small animals as well as those that are young, sickly, old, and weakened by environmental constraints. They are the consummate carrion eater, a trait that no doubt helps them survive the cruel winters in remote and rugged country.

Seekers of wilderness

Wolverines occupy isolated areas of the arctic and alpine coniferous and deciduous regions of the world, and in some of the western regions of the U.S., Wyoming among them. They’ve even been seen as far east and south as Michigan. In North America though, most are found in Canada. Wilderness areas provide excellent habitat and security for the species, which is sensitive to human encroachment. An estimate of wolverine populations worldwide is unknown since generally low population numbers and very large home ranges in especially remote areas make researching the mammals difficult at best.

One young male wolverine tagged by the Wildlife Conservation Society made its way from Grand Teton National Park in northwest Wyoming to northern Colorado, a distance southward of approximately five hundred miles. Male wolverine ranges have been reported at more than 240 square miles, an extensive area that encompasses several females. Females have smaller ranges of approximately 50 – 100 square miles, and overlapping ranges of adults of the same sex are typically avoided.

A study in the Yellowstone region found wolverines in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness and in the Thorofare area of Yellowstone National Park, both in northwest Wyoming. The elevation at which wolverine habitat is found differs from summer to winter, with lower elevations being used primarily in winter. Wolverines typically prefer elevations of 8,000 – 9,000 feet and, if at all possible, try to avoid lower elevations. Since female wolverines are known to burrow in the snow in February to form dens, they are limited to zones with late-spring snowmelt, causing many researchers to be concerned that global warming will reduce the ranges of wolverine populations.

The 21st century wolverine

In the Greater Yellowstone region, wolverines appear to be a rare species with limited distribution. Wolverine populations in the U.S. have steadily declined during the past hundred years due to trapping and loss of habitat. Nevertheless, the species has steadfastly remained in the hidden wildernesses waiting for its time to shine again.

Currently, the wolverine is on the candidate list for inclusion into the Endangered Species Act since the best population estimate points to a species in need of protection with less than three hundred animals in the western U.S., and only one tenth of that number (35) representing successful breeders. In July 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that it will be 2013 before the decision about full protection will be made.

By now, one might ask, “Why should I care about the wolverine?” The answer is: We need to look at the “bigger picture” as far as wolverines are concerned, a picture that means conserving their habitat in an area called the Yellowstone-to-Yukon (Y2Y) corridor. This region is a large and ecologically diverse region, one that encompasses five states (Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Oregon, and Washington), two Canadian provinces(Alberta and British Columbia), and two territories (Yukon and Northwest). Approximately 10 percent of the Y2Y region lies within some form of protected area status, such as wildlife refuges, wilderness areas, and state and provincial parks.

The Y2Y region is one of the world’s few remaining landscapes with the geographic variety and biological diversity to allow species stressed by a changing climate to adapt. And this is one of the keys to ensuring that the wolverine has plenty of space to adapt if necessary to multiple land use of their range.

But just preserving this area will not ensure the survival of wolverines—or any other species, for that matter. The Y2Y eco-region encompasses some of most beloved western haunts: high snow and ice-covered peaks, vast stretches of coniferous and deciduous forests, and salmon and trout filled waterways. A plethora of animal species calls this region home in a natural environment spilling over with the beauty of sparkling clean rivers, green spruce forests, and crystal clear skies. Indeed, these areas remind us of Henry David Thoreau’s words, “In wildness is the preservation of the world.”

Speaking for wolverines, Chadwick puts it best:

“Gulos don’t need a few secure areas to ‘land in between’ to link populations and the genes they carry… As the wolverine becomes better known at last, it adds a fierce emphasis to the message that…other major carnivores keep giving: If the living systems we choose to protect aren’t large and strong and interconnected, then we aren’t really conserving them. Not for the long term…We’re just talking about saving nature while we settle for something less wild. If I want to keep the likes of…wolverines on my place, I’m obliged to make sure they have what they need to flourish. What do they require most today? A fresh idea.”

About the authors

Philip L. McClinton is the former Assistant Curator for the Draper Natural History Museum. In 2005, Susan F. McClinton served as the Information and Education Specialist on Grizzly Bears for the Shoshone National Forest and is currently an adjunct professor in biology at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming. Both have master’s degrees in biology from Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas, and each has a keen interest in animal behavior, conservation, and wildlife education. The McClintons have published and presented a number of articles and reports about their work, including stories in Points West about bats, snakes, lizards, and mountain lions.

Post 025

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.