Kateri the Golden Eagle: Good as Gold – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2013

Kateri the Golden Eagle: Good as Gold

By Melissa Hill

Draper Natural History Museum Assistant Curator and Raptor Program Manager

The eagle let the warmth of the rays wash over her, slowly moving across her feet and up her body until the feathers on the back of her neck glistened like gold. She slowly raised her feathers and shook her whole body vigorously. A cloud of dust and dander surrounded her. It was a morning like any other. Nothing extraordinary for the eagle, but her stomach was telling her it was time to look for food.

With one smooth motion, she opened her wings and launched her massive body off the cliff into the wind. Gliding lazily along the ridge, she scanned the valley below for signs of movement. What would be on today’s menu? A jackrabbit would be wonderful, but she hadn’t seen many lately. A cottontail might be nearly as tasty. She landed gracefully on a small hill that allowed for a great view of the area. Unfortunately, she could see no movement so she waited patiently for her prey to expose itself.

Soon she spotted a cottontail creeping along the prairie, darting between patches of sagebrush for cover. Again, the eagle took to the air, flapping laboriously to gain altitude and the perfect position from which to sneak up on the rabbit. When the moment was right, she tucked in her seven-foot wingspan and sped toward the ground at a 45-degree angle. The rabbit was in her sights with its back to her. As she drew closer, she threw her powerful feet out in front of her body, ready to strike. A moment before impact the rabbit spotted the eagle and dove into a nearby hole. The eagle hit the ground with a thud, sending a cloud of dust into the air. No cottontail for breakfast today.

After a moment of rest, the eagle launched herself back into the air to find a new hunting spot. From the immense height of a power pole, she would have a great view of any critters moving below. She landed at the peak of a pole, glanced around quickly to rule out the approach of another eagle, and began scanning the ground again.

Several hours passed with no significant hunting opportunity. She had even moved to different locations, hoping the prospects would be better. Finally, she spotted a potential meal: a mule deer several hundred yards away. It was not moving as it had recently collided with a car and would make a very easy meal indeed. It wasn’t a great find, but it was a meal nonetheless.

She moved to a power pole closer to the deer and surveyed the area. No other predators had found the carcass. A few ravens and crows had gathered, but they were no match for a golden eagle. Finally, she descended and landed a few feet from the deer, and the corvids immediately scattered. She walked to the deer and began to feed. Glancing over her shoulder occasionally, she made quick work of a hind leg.

When she’d eaten her fill, she spread her wings, ready for the flight back to her cliff perch. But, the meal weighed her down, and it was much more difficult to take to the air. She turned her thirteen-pound body into the wind to gain lift. She heard the familiar roar of a passing vehicle. The sound grew louder and louder.

Whack!

In that one moment, the golden eagle’s life changed forever. She would never again fly free over the open spaces of Wyoming.

Unfortunately, this is a story that comes true far too often across not only Wyoming, but throughout the world as well. This is the story of Kateri, a golden eagle, and the newest “Avian Ambassador” for the Greater Yellowstone Raptor Experience.

As the story suggests, a semi-truck smacked into Kateri. The collision occurred along Interstate-90 in the Powder River area outside Gillette, Wyoming, and resulted in a severe fracture of her right humerus (upper wing bone). Kateri is one of the lucky ones, however, because she received care for her injuries. The majority of wild animals who are injured are killed instantly or are never discovered and die of their injuries.

The amazing people at Northeast Wyoming (NEW) Bird Rescue and Rehab picked up and cared for Kateri. Once at the rehabilitation center, the staff examined and stabilized the eagle until she could be seen by a veterinarian. Due to the severity of the fracture in her wing, the vet performed surgery and placed a pin in the long bone to support the break as it healed. During her recovery, she received meals to increase her strength, shelter to protect her from the elements and predators, and medications to control pain and infection.

Finally, the day came to remove the pin from her wing and begin physical therapy to rebuild her muscles in preparation for returning to the wild. Rebuilding muscle is not easy, and the staff at NEW Bird Rescue and Rehab watched Kateri closely, ever hopeful that she would fly farther and farther, and higher and higher in the flight barn. Unfortunately, that did not happen. She could fly from one five-foot tall perch to another perch of the same height twenty feet away, but she couldn’t move any higher. The realization hit: While the fracture had healed nicely, there was too much damage to the muscle and tissue in the wing for her to regain flight. Kateri could never be released back into the wild.

At the same time, we here at the Draper Museum Raptor Experience of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West had pretty much given up the dream of having a golden eagle for our program. They are extremely difficult to acquire because every program like ours wants one, and very few rehabilitation centers have golden eagles that they are trying to place in permanent homes. Every day, I searched the animal placement postings on the International Wildlife Rehabilitators Council Web site, hoping to discover the perfect bird for our program.

Finally, in late October 2012, I saw a posting for a golden eagle from our rehabber here in town—Ironside Bird Rescue! I immediately called owner Susan to inquire about the eagle, but she already had two other programs interested in this particular bird. The odds of this transfer falling through twice were pretty slim. Luckily, Susan informed me that her rehabber-friend in Gillette had a couple of golden eagles that were not going to be releasable, and I should contact her at NEW Bird Rescue.

I immediately called NEW Bird to inquire about the eagles. After an exchange of messages and missed returned calls, I was finally able to speak to staffer Diane about the eagles she had. She asked what we were looking for, what kind of housing we had lined up for an eagle, and how much and what type of experience I had with eagles.

We had two options for our eagle: either a small, second-year male who had suffered severe head trauma, or a very mellow adult female with a fractured humerus. Diane suggested I think it over and give her a call back in a couple days.

At first glance, the male appeared to be the better choice. None of our volunteers had ever worked with an eagle, and a female eagle can weigh up to fourteen pounds while a male is typically only eight or nine pounds. Simply put: A male would be easier on our arms! A female, however, is bigger and more impressive on the glove, but the size definitely can be harder to handle. Still, the decision was easy for me: Even though her weight might be a challenge, I would rather have a large, mellow bird than a smaller one who might have issues due to head trauma.

As it turns out, that day of “thinking it over” was more for Diane than for me. Like any good rehabber, she wanted to make sure that the bird she had rescued and cared for over the last several months would be going to a great home. Luckily for us, the folks she talked to about me and our program had only good things to say. By November 2, 2012, we agreed that the female golden eagle was ours. Now, I just had to convince the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) that it was a great match, too.

I quickly added the last bits of information to the USFWS Eagle Exhibition Permit Application and reviewed it one last time. I had worked on this application for a year and a half in anticipation of getting an eagle. Finally, in early November, I dropped the eighteen-page application in the mail…and the waiting began.

After two months of agonized waiting, we finally received word on our application. I expected a reply stating that they would be finishing it soon, and that they would get back to me. Instead, the reply simply stated that our approved permit and transfer papers were attached, with hard copies to follow in the mail.

I stared in shock for a few minutes. Finally, I picked up the phone with a shaking hand and called my boss, Dr. Charles Preston, to give him the good news. He was as ecstatic as I was—possibly more so—as he’d been waiting for this moment since he began planning the Draper Natural History Museum in 1998.

A couple more phone calls followed, and we had arranged to pick up our new bird on January 21, 2013. Diane was gracious enough to meet us in Buffalo, Wyoming, and give us a little more information about the bird’s journey from the wild to this point. True to her caring and protective nature, Diane made me promise to be patient and take good care of this amazing animal as she was truly something special. As she carefully moved the eagle from her vehicle to ours, Diane told Kateri, “Be patient with them, they’re only human.”

Kateri has now been with us for seven months and it has been an incredible journey. She received her beautiful and fitting name through a worldwide online contest. Her name means “child of nature” and brings to mind the first Native American saint of the same name. She is doing amazingly well in her training. Since her arrival, we have moved at her pace, never asking her to do more than she could handle or that with which she was uncomfortable. Surprisingly, she’s coming along quite quickly. She’s completely comfortable in her new home, steps onto my glove very willingly and gently, and now works with the volunteers as well.

Kateri now makes appearances in public—she is the “grand finale” of our summer programming. Like all the birds here at the Center, Kateri has a very important role as an ambassador for her species. These birds represent the power, beauty, wildness, and true spirit of the West, and although they can no longer be free, we hope that spirit is contagious and inspires everyone who sees them to take a moment to appreciate what Mother Nature has to offer.

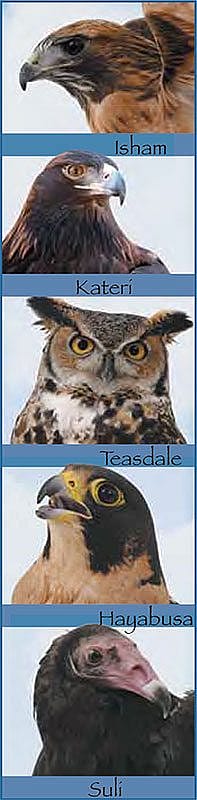

Editor’s note: Since the original publication of this article, the Draper Museum Raptor Experience has acquired a sixth bird, Salem the American kestrel.

Become a follower of our Draper Museum Raptor Experience!

- Click here to visit the Draper Natural History Museum’s Facebook page

- Click here to visit the Raptor Experience’s Blog

Post 031

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.