John James Audubon – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2000

John James Audubon: Feathers to Fur

By Sarah E. Boehme, PhD

Former Whitney Western Art Museum Curator

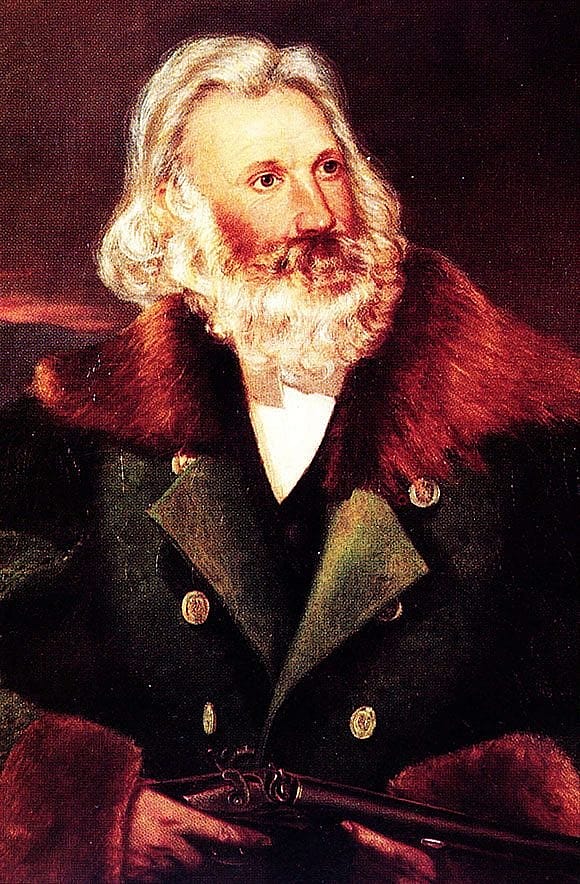

The name of John James Audubon (1785–1851) resonates with associations with artistic images of birds, with conservation issues, and with geographic locations of the Deep South. Audubon does not always immediately spring to mind in listing the pantheon of major artists of the American West, such as George Catlin, Thomas Moran, Albert Biersradt, Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. Yet Audubon in 1843 made an important trip to the West, traveling up the Missouri River as far as the trading post Fort Union. He saw many of the same sites as Catlin and the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, who also portrayed the region in the early nineteenth century.

Just as important as the actual trip to the West are the characteristics of Audubon’s career. What propelled him westward on that trip was an approach to art that would be echoed in the careers of later artists of the West. An examination of Audubon’s life and career reveals both the importance of his own accomplishments and sets the stage for understanding the elements that are important in analyzing western art.

The artistic career of John James Audubon provides the profile of a frontier artist. In the very early years of the nineteenth century, Audubon set out to discover the unknown. He wanted to catalogue and document comprehensively the wildlife in America. It was important that he encounter his subjects personally whenever possible and in their natural habitat. That goal meant that he spent many hours in the outdoors, away from the distractions of civilization, directly studying nature. He believed it was important to know his subjects well and to represent them accurately, yet he also approached his subjects with a romantic sensibility.

As an artist, Audubon was essentially self-taught like many of the American artists who are associated with the West. For many years, America lacked the academies that nurtured European artists, so in the early years of America’s history, artists either learned on their own or traveled to Europe. Although Audubon spent his formative years in France, he sketched and drew on his own, rather than having been a formal student in an academy. He seems to have promulgated the rumor that he studied under the great French neoclassical painter, Jacques Louis David, but that was one of several false stories that for many years were part of his biography.

Another story concerned his birth; a story circulated that he was part of the French royal family, the lost Dauphin. In reality, he was born Jean Rabine, the illegitimate son of Jean Audubon, a French sea captain, and Jeanne Rabine, a French servant girl who died a few months after the birth. He was born in the “New World,” on April 26, 1785, in present-day Haiti. When he was four years old, his father took him to France, and he then lived in the family home in Nantes with his father’s legal wife, Anne Moynet Audubon. He had an idyllic youth, spending much time in the countryside, devoting himself to his interests by sketching, especially birds. He studied briefly at a naval academy but was not a distinguished student.

Young Jean Jacques Audubon pursued art as an avocation, and it would only become his life’s work after he unsuccessfully tried other businesses. He returned to the New World in 1803 primarily to avoid conscription into Napoleon’s armies. Audubon’s father had property in Pennsylvania and sent his son to manage a farm, Mill Grove, outside Philadelphia. He spent his time hunting and drawing birds in the countryside rather than running the farm. His tenure there was, however, very important because he met his future wife, Lucy Bakewell, whose family lived at a neighboring farm.

In 1807 Audubon, with a partner, opened a general store in Louisville, Kentucky. The following year he brought his new bride to Kentucky, and in 1909 their first son, Victor Gifford Audubon, was born. While in shopkeeping in Louisville, Audubon had an encounter that planted the idea for his future work. He met artist-naturalist Alexander Wilson, who came to Kentucky seeking subscribers for his publication, American Ornithology, an illustrated compendium of American birds.

Although Audubon was still an amateur in drawing, seeing examples of Wilson’s work introduced him to the idea that a publication of bird drawings was possible and it inspired his ambition. In 1810 the Audubon family moved to Henderson, Kentucky, which was a base for Audubon as he pursued business in commodities and eventually opened a mill with his brother-in-law, Thomas Bakewell, as partner. A second son, John Woodhouse Audubon, was born in 1812.

All during this time, Audubon actively followed his growing passion for studying birds by sketching, and he began to be successful in representing their physical characteristics. During these years in Kentucky, other sorrows occurred as two daughters born to the Audubons died in their early childhood years. When the mill failed, Audubon was forced to declare bankruptcy and spend time in prison due to his debts.

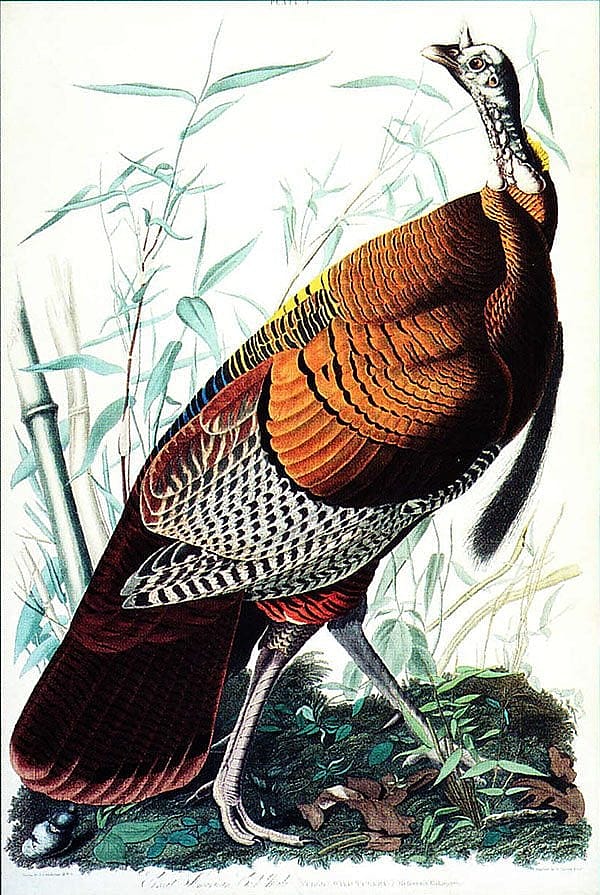

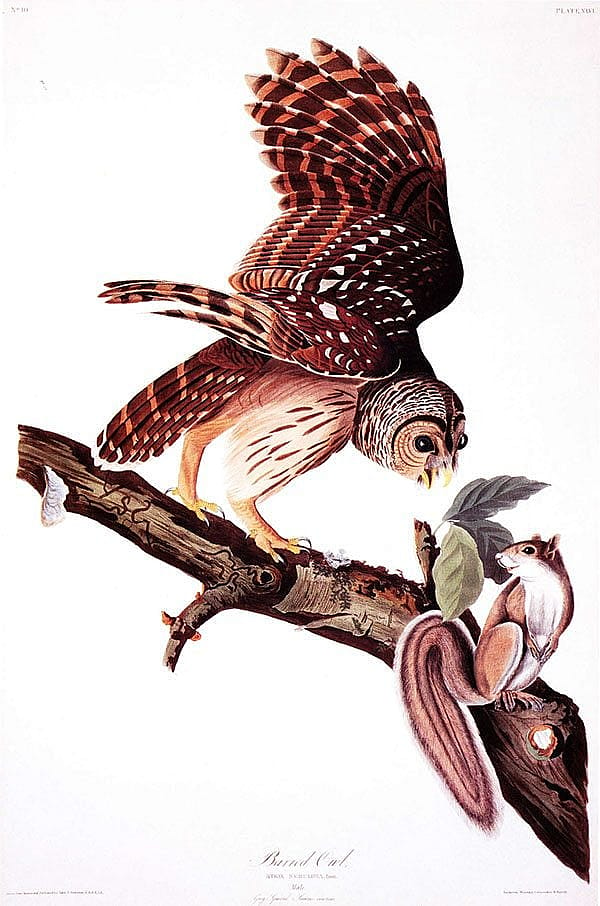

Audubon’s business failures caused him to turn to his art as a way to support himself and his family. He moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, and took a position at the newly opened Western Museum, gathering animal specimens and doing taxidermy. He also taught art and supplemented his income by doing commissioned portraiture. He resolved to put his talents for drawing and his knowledge of bird life to use by embarking on a project to draw every species of American bird and to publish the results. Wilson’s publication stood as the standard, but Audubon believed he could surpass Wilson’s work both by cataloguing more birds, correcting errors and, most importantly, by presenting the birds in more lifelike poses. To do this, it was necessary for him to travel to observe many species. Securing a young companion, George Mason, to accompany him and paint backgrounds, Audubon journeyed to Louisiana in 1820 and spent the next years avidly pursuing his intention to draw birds, while doing some teaching and portrait work.

By 1824 Audubon had a sufficient body of work and sought a publisher in Philadelphia. Unsuccessful there, he looked back to the Old World and journeyed to the British Isles where he showed his bird drawings with some success. He first worked with engraver William Lizars, but production problems caused him to seek another printer. He then teamed with Robert Havell, whose printmaking studio made an important contribution to the success of Audubon’s publishing project. In the years between 1827 and 1838, they produced The Birds of America, a publication of 435 etchings with hand-coloring. Known as the double elephant folio because of the size of the paper, the publication featured sheets measuring 29 ½ x 39 ½ inches, which allowed Audubon to represent the birds in life size.

Audubon followed this extraordinary publication with text volumes, the Ornithological Biography, and then an octavo-sized edition of The Birds of America. That publication would be produced in the United States by the lithographic firm of J.T. Bowen, in Philadelphia, where Audubon had first looked for a publisher.

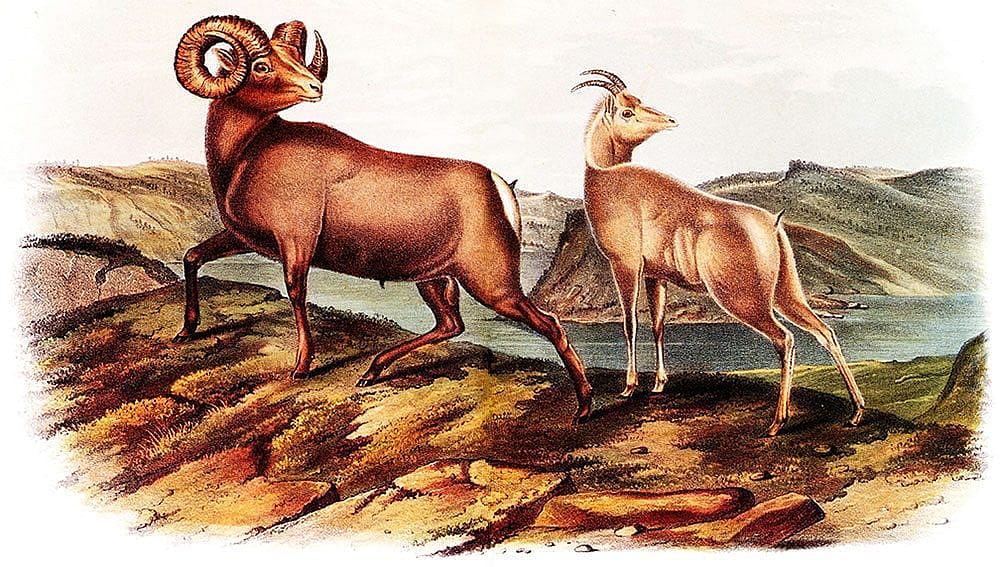

The collaboration with Bowen would be continued in Audubon’s next great project, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, a catalogue of mammals, that would compel Audubon to make that 1843 trek to the Far West to see first-hand the wildlife he wanted to portray.

Post 035

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.