Shooting exhibitions: When “the man who never missed his mark” missed – Points West Online

From Points West magazine

From Points West magazine

Originally published in Spring 2008

When “the man who never missed his mark” missed

By Sandra K. Sagala

In a series of historic newspaper stories, Sandy Sagala discovered the dangers of the popular shooting exhibitions of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Here she paints a picture of the risk to performers and their audiences.

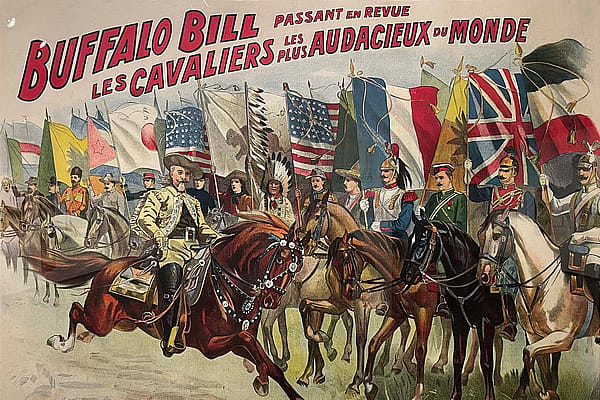

In late 1880, the New York Times announced that over two hundred theatrical companies were touring the country. Of those, nearly twenty starred frontiersmen like William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Dashing Charlie, or Wildcat Ned in melodramas about life on the frontier. The plays, emphasizing western skills like riding and shooting, had much to appeal to audiences.

Marksmanship exhibitions were often so daring as to risk life and limb. The hazards titillated audiences while newspaper editors ruminated on the morbid prospect of horrible accidents. If a bullet caromed astray, some individuals, curious to see a killing or maiming, would be secretly satisfied, even if they wouldn’t admit it aloud. “But,” a journalist wrote in the December 18, 1880, Times, “the tiger is dangerous though he be chained, and those who feed him with such inhuman diet as this deserve some restraint themselves.”

Shortly after Cody began his dramatic career in the early 1870s, he and co-star Texas Jack Omohundro thrilled audiences with warlike dialogue. To demonstrate how it was done on the plains, they instigated a volley of gunfire and knife-slashing. In their over-exuberance during one simulated Indian fight, an actor named W.J. Halpin was inadvertently stabbed in the abdomen, a casualty that apparently escaped being reported to the press.

When he worked with fellow scout Jack Crawford, Cody customarily gave him responsibility for preparing the blank cartridges he used onstage. Once, Crawford delegated the job to a property man, telling him to stop the end of each shell with paraffin. The man thought a tallow candle would do, so he poked candle grease into the cartridges. The first shot melted the wax and sparks set off all the other cartridges. This time, no one was injured.

Crawford himself was not so lucky. In June 1877, during a performance in Virginia City, Nevada, he was engaging Cody in a fight on horseback when he drew his pistol and accidentally shot himself in the groin. Crawford fell from his horse and blood began to soak his pants. Fellow actors carried him to his dressing room where a doctor deemed the wound not serious even though Crawford needed crutches for a few weeks.

Possibly the most humorous of theatrical mishaps involved Frank Mayo, who played Davy Crockett for over a quarter century. In a June 19, 1880, story, the New York Mirror reported that stagehands were in the habit of scattering dry leaves around the stage for the first act of Mayo’s performance. To recycle the leaves, when the curtain went down, they swept them onto center stage’s trap door to be dropped and bagged. During a Detroit performance, Mayo hurried to cross the stage after the first act and strode through the pile. Instantly, he disappeared, dropping down eighteen feet. One of the troupers could not resist remarking that he “took [his] ‘leave’ rather suddenly.” Only Mayo was not amused.

While misfortunes involving actors were regrettable, danger to the audience was unthinkable. In Baltimore in September 1878, while charging his horse up a fake mountain, Cody fired at his Indian pursuers. The shot went wild and struck a young man in the audience. His lung punctured, the boy was not expected to last the night. Cody said he checked his gun previous to show time and the ammunition would hardly penetrate a cigar box. The boy did recover, and Cody transported him to his Nebraska ranch for further recuperation. Nevertheless, newspapers condemned the recklessness and hoped the tragedy would lead to reform.

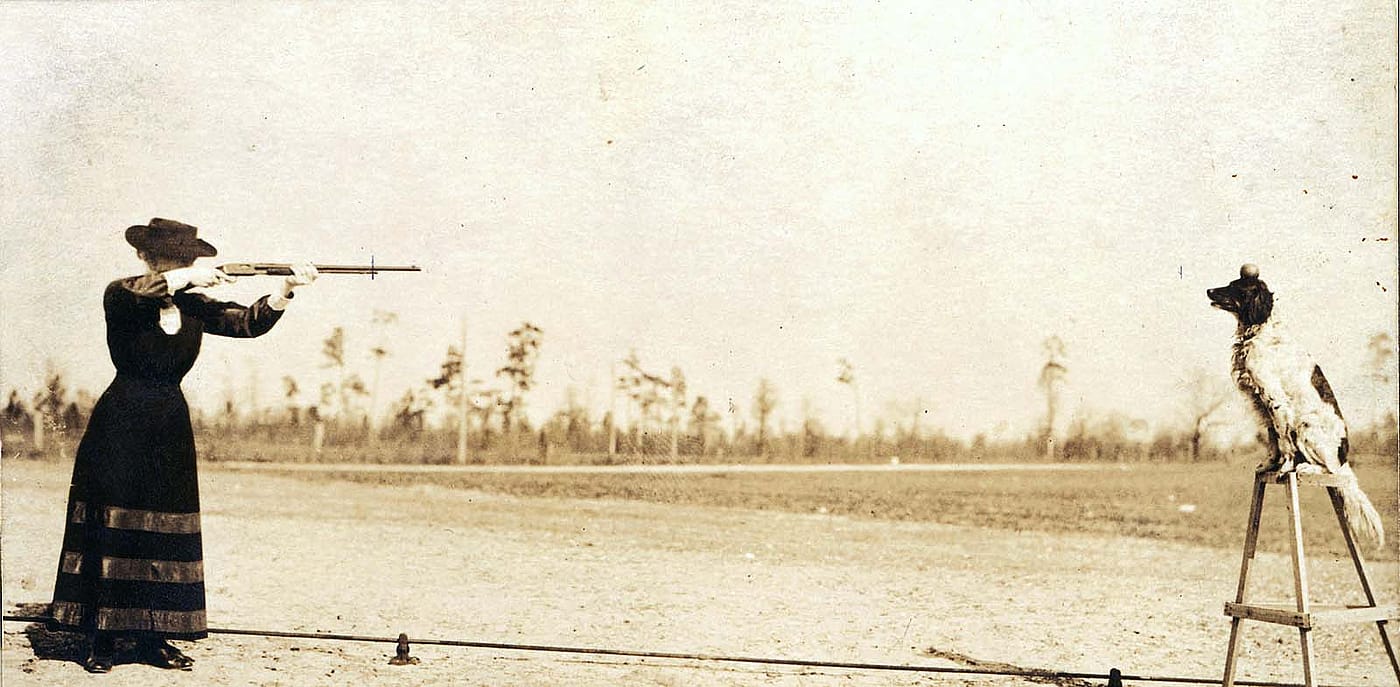

Cody had been fortunate compared to others. Earlier that year, Jennie Franklin, née Fowler, often exhibited feats of reckless marksmanship. She had no regular assistant but asked members of the company to stand and serve as targets. One night in April 1878, Miss Franklin, after warming up by firing at a target, then split an apple placed on the head of volunteer Lottie Maley, a 24-year-old trapeze artist known onstage as Mademoiselle Volante. Maley—daring “almost to foolhardiness,” a friend said later—had expressed a desire to become famous, “to create a sensation.”

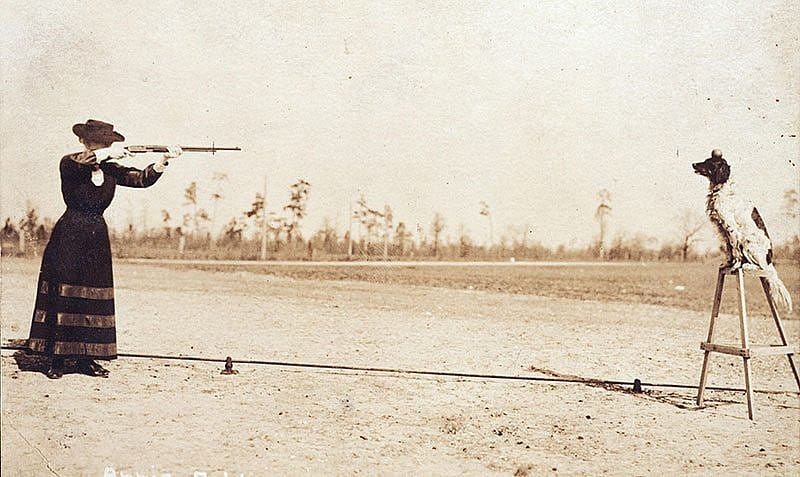

To intensify the performance, Franklin turned her back to her target and aimed by means of a mirror placed on one side of the stage. A shriek sounded through the theatre simultaneously with the rifle’s report. Spectators were horrified as Maley fell forward. Death was instantaneous; the bullet had pierced her brain. It was ruled “an unfortunate accident.”

Once again, the press called for a stop to such exhibitions, but it was not to be so. One newspaper told of one man who, confident another marksman’s spectacle would end badly, hoped to see it for himself. He routinely haunted dramas from a secure place, wherever there might be such danger. A few years would pass, but it inevitably happened again.

Frank Frayne entered dramatics in Cincinnati and, in a few years, he became the stock actor of a traveling company. Success impersonating leading tragic characters eluded him though. Consequently, he abandoned the stage for the West, where he became an expert shot with both rifle and pistol. He decided to return to the stage to give marksmanship exhibitions in melodramas where his wife, Clara Butler, also acted. During shooting matches, she showed as much nerve and accuracy of aim as Frayne did. Their performances proved popular, although the press continued to condemn their dangerous aspects. Nevertheless, they called Frayne “the man that never missed his mark nor wastes a cartridge.”

If there is such an egregious honor as having the most horrific accident, Frayne earned it in Cincinnati’s Coliseum theatre during the crowded 1882 Thanksgiving Day matinee. After Butler’s death from disease, Frayne and his new leading lady, Annie Von Behren, were performing in Si Slocum, “a sort of travesty on William Tell.” In the fourth act, the villain demands that Si’s character shoot an apple from his wife’s head, saying: “It must be with the backward shot.”

Frayne made the usual preparations and von Behren took her position about thirty feet away, wearing a hat she had recently purchased. Its crown was about four inches high and, if she wore it lightly on top of her head, the apple placed on it had its center six inches above her scalp. Frayne planned to aim above the apple’s center. He turned his back, placed the rifle over his shoulder, and took aim using a mirror. He fired, and the lady instantly fell without a word or groan when the ball struck two inches above her left eye.

Frayne cried, “My God, I’ve shot my Annie.” After lowering the curtain, the manager dismissed the audience saying the injury was slight, but the play would end without the fifth act. The surgeon who responded could do nothing, and Von Behren died minutes later.

Frayne and Von Behren had planned to be married. He was so overcome with grief that, at his arrest, he told police to charge him with the very worst they could; he had no desire to live. Theatre manager Heuck summoned his attorney and attempted to secure bail for Frayne, but it was refused. Later, Judge Higley of the police court agreed to a $3,000 bail for Frayne after he heard the circumstances of the incident.

At the coroner’s inquest, friends testified to Frayne’s sobriety and soundness of mind. None knew of any trouble between him and the victim. When called on to explain what happened, Frayne said the light was good and his eyes in good condition. He had used the same gun for six years; he insisted it was clean and in working order but, when he fired, he heard the catch-spring strike. A flash burned his shirt collar, and he saw that the cartridge shell was partly blown out. When a gunsmith examined the rifle, though, he found it to be in such bad shape that he was surprised an accident had not happened before.

The weapon was a three-foot-long, single barrel, breechloading rifle that carried a .38 caliber ball. It worked on a pivot and was held by a spring. The stock supported a mirror for use in sighting backward shots. The tongue of the barrel fit into a slot, which in turn was held by a screw. When the hammer struck the cartridge, the explosion threw the screw out of place, causing the barrel to deflect enough to do its deadly work. Others saw flame flash near the lock, corroborating Frayne’s statement that the barrel at its breech had become displaced.

The prosecution argued that a statute forbade pointing a loaded gun at or toward another person. Frayne’s counsel claimed that the statute was not flouted because the gun was pointed at the apple. He also suggested Frayne had already suffered the worst that could happen to anyone, and that no punishment could add to the lesson of the accident. Higley declared the testimony clearly showed there was not the slightest criminal intent, and the prisoner should be discharged. Frayne presented his rifles to Cincinnati police lieutenant Benninger and to his lawyer A.C. Campbell, swearing he would never again participate in any feature which could endanger the lives of the performers or of the audience.

Perhaps he meant by gunfire. Frayne shot at no more apples but, to attract audiences, he imported wild lions.

The press in Auburn, New York, joked that an accident insurance office would have to be installed in every theatre: Accident tickets good for three hours, only 25 cents. A few months later, one of the lions, tired of being hunted, stalked a little on his own and tore away Frayne’s coat and “a useful portion of his pantaloons.” A reporter for the New York Times and Express regretted that the lion lost the opportunity to create a sensation by swallowing Frayne, bones and all.

Despite calls for reform, twenty years after Frayne’s accident, William Tell acts continued to be popular. Charles Meinel’s act involved shooting an apple from a volunteer’s head. On one afternoon in October 1902, 18-year-old John Volkman expressed a willingness to hold the apple. Customers in the barber shop where he apprenticed tried to dissuade him, citing the risk. One went so far as to bid him good-bye and asked where he wished to be buried. Volkman’s employer even delayed work in the shop in hopes the performance would be over before Volkman could reach Long Island’s Thespian Hall in time to volunteer.

Meinel did not appear to be in good shooting form and had been jeered a short time before due to missing his target. Once the apple was placed on Volkman’s head, Meinel shot from a distance of twenty feet. His first two shots failed to hit the apple, but the third struck Volkman in the forehead. Dr. Soder, the show’s manager, rushed to Volkman’s side, and a doctor was summoned. They extracted a part of the bullet, but fragments had penetrated the frontal bone. Volkman died within an hour. Meinel was charged with manslaughter. He had been in show business twenty-five years and, despite similar exploits, had never before had an accident.

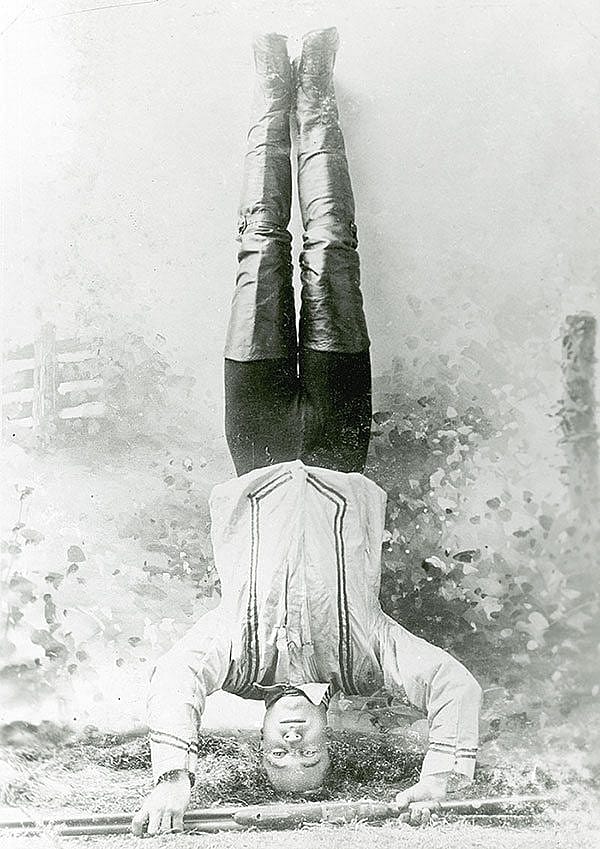

Titling his article “One Good Result,” a Cincinnati Enquirer journalist writing in 1882 described the contortions shooters had exercised to perform such treacherous feats. From shooting while standing on their heads to firing while leaning across the back of a chair with head thrown back, marksmen executed increasingly perverse gymnastics to incite audiences’ fear and wonder. However, after accidents such as Frayne’s and Franklin’s, most performers eliminated human targets in favor of glass balls. The danger was not so ghastly; the excitement not so impressive.

But there would always be a next time.

Sandra K. Sagala’s revised manuscript on William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s theatrical troupe, Buffalo Bill On Stage, was published in May 2008 by University of New Mexico Press. Her article comparing Buffalo Bill with Mark Twain was serialized in these pages, the winter 2005 through fall 2006 issues. She also co-authored Alias Smith and Jones: the Story of Two Pretty Good Bad Men (Bear Manor Media 2005). Sagala lives in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Post 038

[jetpack_subscription_form title=”Subscribe to our blogs!” subscribe_text=”Enter your e-mail address and click “Subscribe” to sign up for e-mail notifications of new blog posts.”]

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.