Carbine: Uniting Man, His Horse, and His Firearm – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 1994

Carbine—Uniting Man, His Horse, and His Firearm

By Howard Michael Madaus

Former Curator of the Cody Firearms Museum

CARBINE. (F carabine, carbine, carabineer fr. MF carabin harquebuseer…) 1a. a short-barreled shoulder arm used by cavalry. 1b. any short-barreled lightweight rifle.

2. a. a light automatic or semiautomatic military rifle using ammunition of relatively low power and often issued to troops that are not primarily riflemen.

Thus Webster defines one of the more confusing words in firearms terminology. To understand its various meanings, it helps to know a little about the problems that marksmen historically have encountered in loading and firing a firearm, especially a shoulder-arm, while riding on horseback.

The “carbine,” or “carabin,” as it was then known, evolved during the warfare of the sixteenth century. By 1550, the military use of firearms had become widespread among the armies of the nascent states of Europe. Nearly all used for military purposes were single-shot, muzzleloading, smoothbore, and dependent on either an only partially reliable or a complicated and expensive ignition device.

The foot soldiers utilized a simple matchlock musket perfected by the Spanish, the arquebuse. It was so heavy that its handler required a forked pole upon which the barrel rested while “aiming,” which in reality usually meant pointing the barrel in the general direction of the enemy and trusting the gods of battle that someone would be struck by the projectile. Once the firearm discharged, the soldier was forced to retire behind the protective rank of fellow musqueteers or pikemen to slowly reload it from the muzzle with hollowed wooden cartridge containers appended to the leather bandolier crossing his chest.

The horse soldiers for the most part considered their firearms as secondary weapons, inferior to the sword and only useful when it was impossible to get within slashing distance of an enemy. The firearms, usually a pair of pistols, were carried not on the soldier’s person but in a set of holsters that straddled the pommel of the saddle. Because their barrels were short and their bores smooth, the guns were necessarily inaccurate. Because it was nearly impossible to keep the glowing piece of hemp that ignited the foot soldier’s arquebuse lighted while on horseback, the pistols of the horse soldiers usually incorporated the more effective but expensive wheel-lock mechanism of flint and steel to ignite the powder charge. Once he fired, a horseman had to stop his mount and secure the reins to reload, which required both hands.

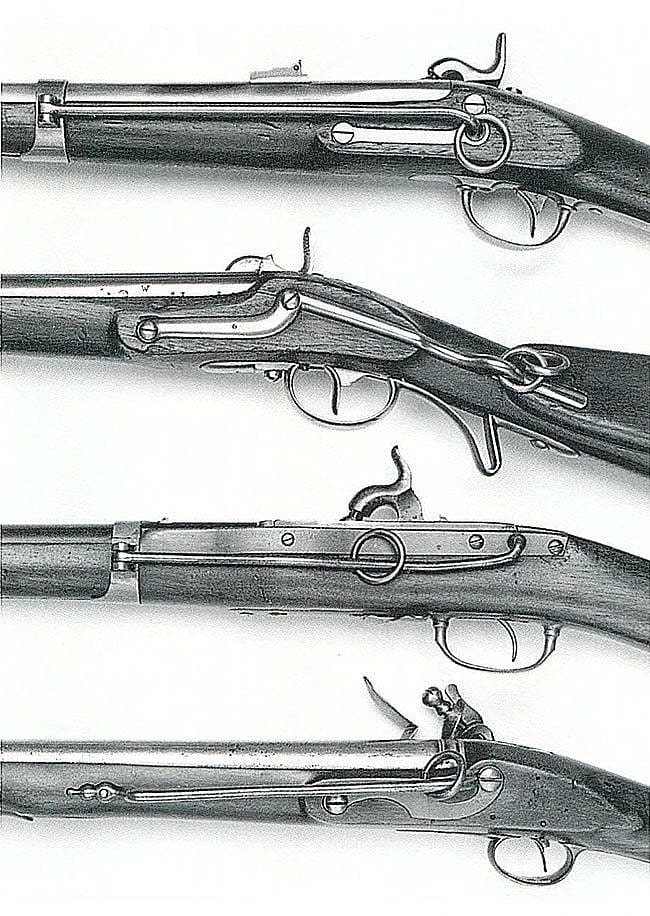

The carbine evolved as a means to combine the greater accuracy of the foot soldier’s musket with the flexibility of horse soldier’s pistols. The initial “carbines” were simply shorter versions of muskets, retaining their large-bore diameter but reducing the weight by shortening the barrels. Later the bore diameter was decreased to further lighten the barrel. These early carbines were attached to the horse soldier’s belt by an elongated hook on the left side of the arm, what the Germans called the karabenierbaker (carbine hook).

With the standardization of military arms in the first half of the nineteenth-century, another method of securing the carbine to its owner was devised, a snap clasp on a bandolier crossbelt that locked into a sliding ring on a bar attached to the left side of the stock. This method not only prevented the loss of the weapon but, equally important, also provided a way to load in the saddle with one hand.

Thus was born the most distinctive characteristic of the eighteenth- and nineteenth- century carbine—the “sling ring.” This ring was an integral component of the standardized carbines adopted for the English military service in 1756 and the French in 1763. It was a feature that would be copied into the military carbines and musketoons of the American service, beginning with the first carbines adopted in 1833 and continuing until the beginning of the twentieth century.

In military service, the carbine was secured to the horse soldier by means of a crossbelt that terminated at the soldier’s right side with the clasp that locked onto the ring. To prevent the muzzle from flopping as the horse moved, a small leather ring was initially attached to the saddle through which the muzzle extended when the carbine was not in use. In the post-Civil War period, this loop was replaced by a half scabbard.

Civilian carbines, although also distinguished by the sling ring on the left side of the frame, were not furnished with the military style crossbelt and clasp. Most civilians carried their carbines in full leather scabbards when not in use. When in use, the carbine was carried across the pommel of the saddle, and a leather thong looped through the ring could be used to secure the carbine to the pommel tree. In carrying the carbine across the pommel with the barrel parallel to the ground, the western civilian copied the practice long used by the American Indians. The well-worn forestocks of identified Indian-used guns invariably evidence the practice of carrying the longarms balanced across the saddle tree.

In 1942, the United States Army officially discontinued the horse-mounted cavalry from the service. The demise of the horse, however, did not end the life of the military carbine. In place of a shorter’ lighter longarm adapted for horse service, the army adopted the M-1 carbine, a lightweight, short ripe utilizing a cartridge smaller and less powerful than the standard military rifle cartridge. The new carbines were intended for troops whose functions would be hindered by the length of the standard military rifle or whose combat role did not require long range practice.

Since the horse was no longer in service, the sling ring that had so long characterized both military and civilian carbines was done away with. The name, however, persists, so that now any short, lighter-weight rifle is often classified as a “carbine,” whether horse borne or not.

Post 043

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.