Our Boy Butch Cassidy – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2001

Our Boy Butch

By Marik Berghs, Guest Author

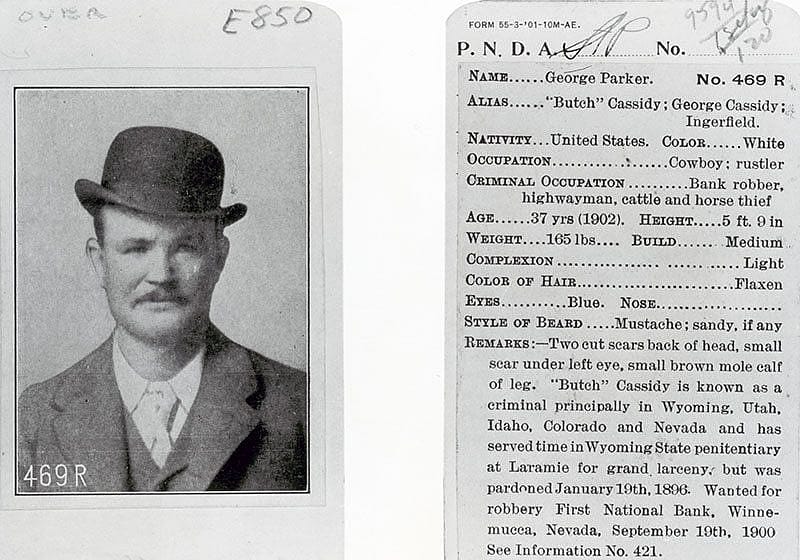

He caroused the wild towns of Arland and Andersonville and bellied up to the Cowboy Bar in Meeteetse. He sashayed through this area, perhaps with stolen stock or outlaw compadres. Yep, Robert LeRoy Parker was here, all right, but we just called him Butch. Cassidy, that is.

He was no doubt one of the most respected and well liked of the outlaws. An early Wyoming newspaper editor related, “I never met a man that didn’t like Cassidy…but then, I don’t know all the bankers.”

Cassidy worked, served time, rustled, hid, partied, lived and loved here. Today, he is still called by some the “gentleman outlaw.”

Born in 1865, he grew up in Utah, grandson of a Mormon bishop. At age 13, young Roy let himself into the locked local general store, leaving a note promising repayment. The storekeeper swore out a complaint, marking Roy’s first run-in with the law.

The eldest child, Roy worked for ranches to supplement the family’s living. At the Marshall Ranch, he took to an amiable drifter named Mike Cassidy who taught the young man about horses, guns, cattle, and rustling. Roy had found a release from weekly religion classes and hard work.

In 1884 his rustling was found out and he set out for Colorado. Cassidy’s outlaw life, along with his Hole-in-the-Wall gang also known as the Wild Bunch, spanned 19 years across at least a dozen states. After his prison stint, he took up the life of an outlaw in earnest. But true to the pact formed between small settlers and rustlers, pioneers remember him as friendly and generous.

His time in Wyoming was spent in west central Wyoming near Lander, northwest to Dubois and northeast through the Wind River area to present-day Meeteetse.

Due west of the famous Hole-in-the-Wall, the Thermopolis and Andersonville area was a natural retreat for outlaws like Cassidy since county seats changed from year to year, and the nearest law was 60 miles away in Basin, Wyoming. The next nearest sheriff was 90 miles away.

It is said that Cassidy worked for the Embar Ranch near Thermopolis, Wyoming, during the summers and briefly wintered with a friend eight miles north of present Thermopolis.

The Wild Bunch disappeared to the Hole-in-the-Wall when the circumstances warranted. The Hole-in-the-Wall in the Big Horn Mountains is a V-notched valley. By sliding a boulder across the notch in the wall’s cleft, no trail could be traced. Two miles away, makeshift corrals awaited stolen animals. This conduit foiled range detectives for years and allowed the Wild Bunch to operate until it was discovered in 1897.

It is believed that Cassidy never shot and killed anyone, but on two occasions, he had close calls.

At the Sherard Saloon in Andersonville, Wyoming, he shot at the rung of a chair to wake his sleeping friend, “Irish” Tom Walsh. Instead of hitting the chair rung, the bullet caught Tom in the leg.

Another time in the same saloon, Butch shot the tassel off the black cook’s hat—narrowly missing his head. Obviously, Cassidy was an expert marksman who liked to have a good time. Not all his contacts returned the amicable feeling.

Otto Franc, owner of the Pitchfork Ranch near Meeteetse, was one of the land barons determined to nail rustlers to the wall and protect his own livelihood. Cassidy had “bought” three rustled saddle horses, although legal paperwork was never completed. During Cassidy’s trial, Franc charged that Cassidy and a buddy (whom Butch suspected was connected to Franc) had committed grand larceny. Cassidy was found guilty of stealing a $5 horse; his friend was let go. Public sentiment prompted Cassidy’s pardon by Wyoming Governor W.A. Richards on August 9, 1896.

After his release from prison, Cassidy was determined never to go back. He rounded up his gang and began his life of banditry with the Wild Bunch by robbing a bank in Idaho.

His doings were spiced by clandestine meetings with sweetheart Mary Boyd in Lander, Wyoming, train robberies, honest but short-lived jobs, good horses, travels with the Bunch, and stolen money given to women in need and friends in trouble.

Westward expansion was taming the frontier, however, and technology was improving communication. Posses were hired and the Pinkerton National Detective Agency tracked Cassidy. The Wild Bunch disbanded in 1901.

The lore of Cassidy saturates Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin. Abby Tillot of the TX ranch recalled the following family legend. “John Ellsbury, my dad’s cousin, was an orphan at the age of 8. He was sent to live with a man who was so mean he kicked a cat to death. Apparently he was not above attempting to do the same to John. The young Indian boy (of Cree, Chippewa and Assiniboine descent), finally ran away. He found a ranch with a group of cowboys who treated him better. Whenever strangers approached, however, he ran away and hid.

After one stranger rode up and talked with the men, a cowboy came to the shack where the boy was hiding and talked him into visiting with the gentleman.

He said he was John’s uncle. It took awhile to convince the child because he was certain he was alone in the world. But after some time, the boy agreed to go with the stranger. They traveled thirty days to get back to the uncle’s ranch. On the trail the boy was wary and expecting the worst. Once the older man killed an owl and told the boy they would be having it for supper. The boy was horrified. Unknown to him the uncle had also bagged two quail that he was cooking but it took the longest time to convince John to partake of the meal.

They reached the uncle’s ranch and after a few days a man rode up leading a horse. He said his name was Thorndike. He looked like he’d been through some rough times. Thorndike said he needed John’s help and asked if he would work for him through the summer. John agreed and mounted the extra horse. For the next 3 – 4 years he worked for Thorndike. His job was curious. Mr. Thorndike employed several cowboys who didn’t seem to accomplish much but race Thorndike’s best horses up and down the prairie.

There were four corrals of horses. John was responsible for graining and feeding hay to horses in three of the corrals. The fourth corral held unusually fine horses. Though John worked with horses all his life and developed a reputation for it, he never saw horses like the horses contained in that last corral. He was allowed to ride one once and never forgot how wonderful the creature was. The cowboys taught John a lot about horses and generally treated him well. Mr. Thorndike was a nice man and John became known as Mr. Thorndike’s range orphan.

It wasn’t until some time later that he came to know Thorndike had other names, one of which was Butch Cassidy and that the famous fourth corral of horses contained the outlaws’ getaway mounts.

John worked for Butch after he had been “killed” in Bolivia, the popular version of the end of the Wild Bunch as shown in the movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

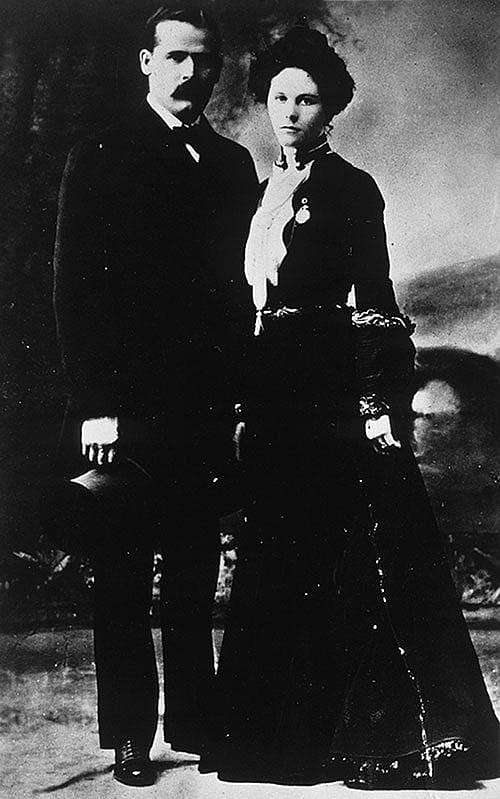

This is not the only incident of Butch’s life that area old timer’s claim defy the accepted version of his Bolivian standoff. A story from the Wind River Indian Reservation is purported to have come from a “front man” for his bunch. This man claimed to have been told by Butch that they had never gone to South America. Butch and Sundance went to Arizona where they talked a greedy pair of greenhorns into going to South America to pick up their cache of cash. Legend goes that the greenhorns traded clothes (the clothes made historic in the famous Hole in the Wall photo) and took off, certain they would soon own the rainbow’s treasure.

The federales ended their career. There was not much left to identify from those corpses with the now-famous photograph sent from the States except the clothing they wore, which matched the picture of gentlemen in some fancy clothes. This legend goes on about how Butch came back to Lander and the Lander area to live out the remainder of his life. Other local legends claim he returned to the States using the alias William T. Phillips, married, had a family and became an inventor and businessman in Spokane, Washington. He revisited Wyoming in the 1920’s and 1930’s and even met Mary Boyd in Riverton, Wyoming, then a widow. William T. Phillips died in 1937 of cancer, depressed, bedridden, and broke.

It is not known for certain where and when Roy Parker, alias Mr. Thorndike, alias William T. Phillips, met his demise. Perhaps that is only a reflection of the affection in which people held him. He was a western Robin Hood and many stories circulate of his genial personality. Perhaps the smoke around the facts of his death explains the unwillingness to surrender Butch and Sundance to the merciless fusillade of hostile bullets.

Many say, as if to honor our naughty boys and hold them dear, “After all, he never meant to hurt anyone…”

Post 045

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.