Catlin Showed Us – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2000

Catlin Showed Us

By Edith Jacobson

Former Intern, Whitney Western Art Museum

By the 1830s America was beginning what is now known as “The Era of Westward Expansion.” What did those first settlers know about the West? What did they expect? At that time, the American frontier was the land west of the Mississippi River. Early exploring expeditions such as Lewis and Clark’s in 1804 produced many words about the unknown frontier, but few, if any, images. So even though the public read about the West, they still knew very little about what this area looked like.

When George Catlin embarked for the West in 1830, it was the first major attempt by an artist to factually document the West in images. Catlin eventually went on five different trips West, produced more than 600 paintings, toured these paintings in exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe, and published more than 10 books that included reproductions of his paintings along with a text. Some of these books went through numerous editions. His paintings were also reproduced countless times, legally and illegally, in newspapers and magazines. Because his paintings were the first of their kind, and because they were so widespread, they had a huge influence on the perception of the West.

First Look

Although George Carlin is best known as an early American artist who documented the American Indian, he also painted a number of buffalo scenes. And just as Catlin’s paintings of Indians were the first glimpses of an Indian for most people, Catlin’s paintings of buffalo were the first images of buffalo seen by most people.

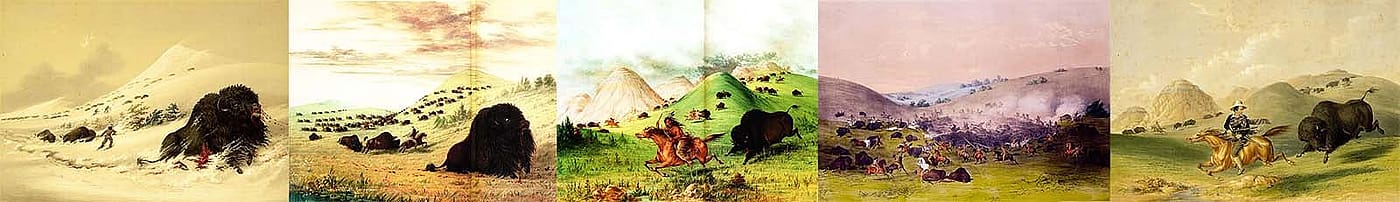

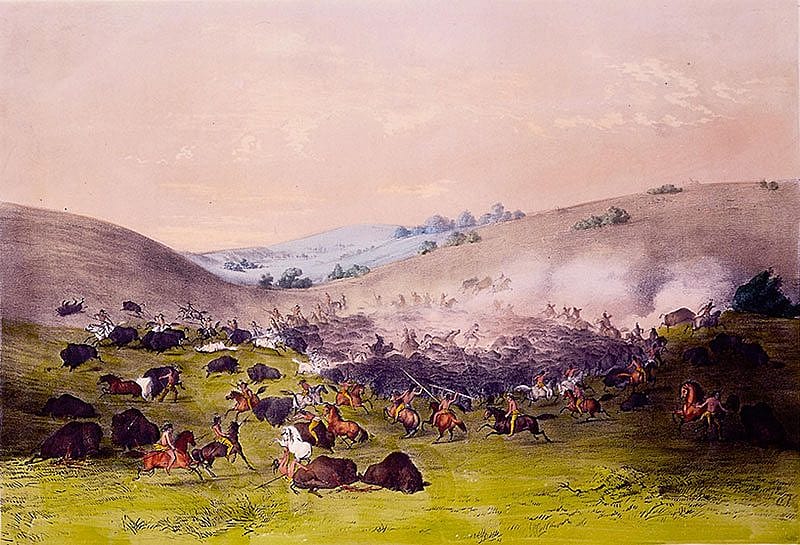

Probably the most well-known of Catlin’s buffalo paintings were 13 buffalo scenes included among the 25 prints in his North American Indian Portfolio: Hunting Scenes and Amusements. This portfolio of hand-colored lithographs was first published in 1844 in England, directed mainly at well-to-do British who could afford—and whom he hoped would buy—his works. In the portfolio there are 13 prints with buffalo. Of these 13, 12 portray hunting, 7 portray dying buffalo, and 9 portray the chase of the buffalo. Only 1 out of the 13 prints portray any kind of grazing buffalo.

It was a romantic time

These highly romanticized scenes were popular among the culture of the day. This does not mean they were not factual, but rather that Catlin chose to portray the exotic and wild over the daily and mundane.

Despite Catlin’s extensive works, he struggled financially throughout his life. Catlin’s income depended on the public’s acceptance of his work. Even if Catlin would have personally chosen to depict the buffalo in different situations, his paying audience wanted more dramatic scenes. So Catlin’s art reflected the romantic tastes of the time: the 1830s and 40s. Thus, the buffalo was portrayed as a beast of prey, sometimes with the Indian, white hunter, or wolf in pursuit, other times in its final stages of death.

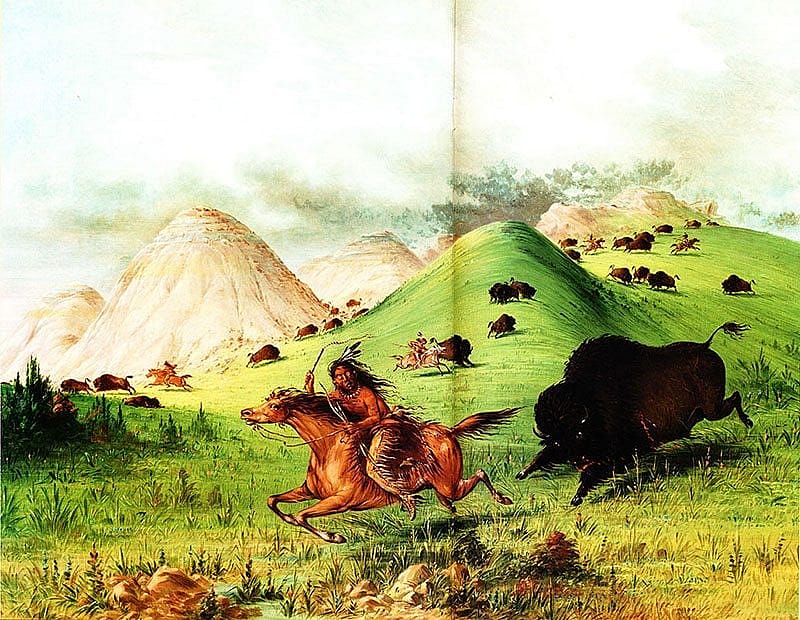

In romanticizing the buffalo, Catlin also romanticized the West. His hunt scenes produced an image of an animal meant for hunting and the use of man. Buffalo Hunt—Chasing Back offers an image of a powerful, unpredictable, and untamed animal. This is not unlike the popular image of a wild, unpredictable, and untamed West.

Catlin cared

Although Catlin often depicted the buffalo in a dramatic hunt scene, sometimes even including himself in the painting, he was concerned about the reckless and wasteful killing of the buffalo. In Letters and Notes, first published in 1841, Catlin openly criticized the mass killing of buffalo precipitated by fur companies. He wrote, “It seems hard and cruel, that we civilized people with all the luxuries and comforts of the world about us, should be drawing from the backs of these useful animals the skins for our luxury, leaving their carcasses to be devoured by the wolves…, the buffalo’s doom is sealed.”[1] Catlin’s doomsday prophecy that the buffalo would disappear in “eight or ten years”[2] didn’t come to pass, but his concerns were valid. The buffalo did disappear from most of the United States and was in danger of extinction.

Fact or convention?

Part of Catlin’s fame originates from his claim that all of his paintings were factual, firsthand experiences unlike most of the earlier images of the West. However, one of the controversies surrounding George Catlin today is how factual his paintings really were—especially his winter scenes. All of Catlin’s western expeditions took place during the summer so it does not seem likely that he ever witnessed any snow scenes. There is the chance, however, that he was caught in an early or late winter storm, which was not entirely unusual for the prairie. Thus stems the controversy.

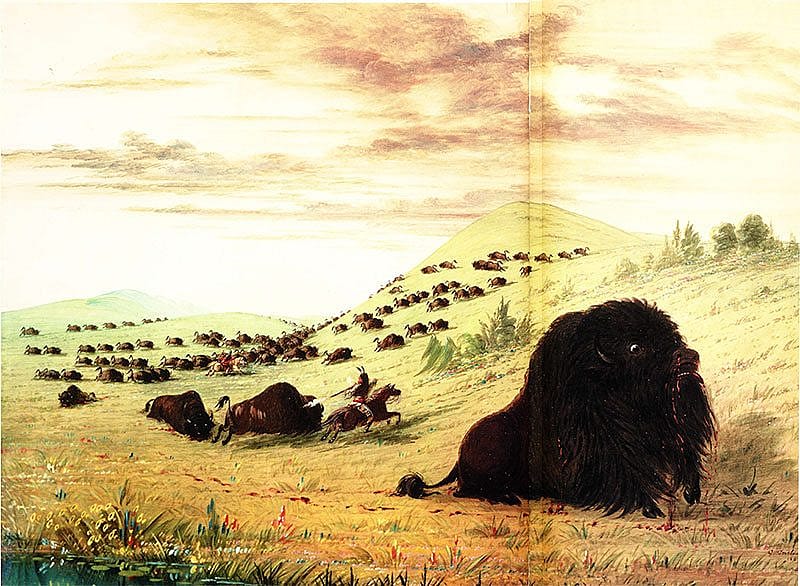

One of these winter scenes was published as print no. 17 in Hunting Scenes and Amusements, Buffalo Hunt—Dying Buffalo in a Snowdrift. This print is remarkably similar to Catlin’s 1863 oil painting, Buffalo Hunting. The Indians in the paintings simply switch from being on horseback to snowshoe while snow replaces prairie grass and flowers. But besides these differences, the compositions are almost identical in placement of hills, buffalo, and Indians. Based on these paintings, it seems that Catlin could easily take a summer composition, alter it a little, add snow, and claim that it is authentic.

Not just seasons

But searching a little further, one realizes that Catlin also used the same compositions from one summer scene to another such as print no. 12 in Hunting Scenes and Amusements, Buffalo Hunt—Chasing Back, and the (ca.) 1846 oil painting, Buffalo Hunt—Chasing Back. Both of these scenes are set during the summer, but this time Catlin switches his friend, Charles Murray, with an Indian, while leaving the composition basically the same. This additional example shows how Catlin often reused a successful composition. Although he had first-hand experiences, he frequently composed his paintings and prints in his studio from memory or invention.

Information and inspiration

Whether or not every image was a statement of fact. Catlin’s art still remains an invaluable source of first-hand information about not only the early West, but also about buffalo of the early West. He was the first artist to give people back East and those who would settle the West an authentic idea of the West in more than words. This idea not only helped shape the romantic image of the West that still lingers with America today, but inspired countless adventure-hungry souls to leave their homes behind for new lives in the American West.

Endnotes

[1] Catlin, George. Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of North American Indians, Vol. I. Minneapolis: Ross & Haines. lnc., 1965 (first issued 1841), 263.

[2] Ibid, 263.

Post 052

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.