Anatomy of the Paul Dyck Plains Indian Buffalo Culture Collection – Points West Online

From Points West magazine

Originally published in Summer 2011

The Anatomy of a Collection: One Object at a Time

The Paul Dyck Plains Indian Buffalo Culture Collection

By Anne Marie Shriver and Rebecca West

A blue metal locker, labeled “#23” in black ink on a piece of tape, rests in a storage room among other boxes and bins. The locker is unremarkable and a bit worn, in contrast to the uncommon contents inside.

Rare objects—plain and beautiful, created and used for survival, made with remarkable artistry—are representative of the cultural diversity, history, and identity of Plains cultures. These are the individual pieces of the Paul Dyck Plains Indian Buffalo Culture Collection.

In February 2006, the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] welcomed the loan of approximately two thousand objects from the Paul Dyck Collection. With excitement and anticipation, the staff awaited forthcoming negotiations to acquire the collection. The Dyck Foundation still owned the collection, and the relocation of its contents from Paul Dyck’s home in Arizona to Cody, Wyoming, provided an opportunity for both parties to fully assess the collection’s holdings, condition, and immediate storage and conservation needs. A successful artist, Paul Dyck (1917 – 2006) systematically assembled the objects during his lifetime, adding to a collection started by his father in 1886.

Dyck filled his home with the items that became his devotion as he diligently acquired, documented, and researched objects from a period he identified as the “Buffalo Culture” era. He formed lifelong friendships with Plains Native people to expand his knowledge of their cultures, and also to acquire significant pieces. Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board member Rusty Rokita comments on Paul Dyck’s methods as a collector, “There are undoubtedly rare and old items scattered about the world, and there are obviously other important collections of ethnographic material, but when it comes to Plains Indian material, this is a ‘collector’s collection.’ It was carefully designed and crafted to include as many important items as possible.”

the formal acquisition of the collection in September 2007, the Center obtained Paul Dyck’s work and promised to protect the physical and cultural integrity of the objects. Speaking to the Center’s role not only in protecting, but also sharing the collection with various groups, Emma I. Hansen, Senior Curator of the Plains Indian Museum notes, “Bringing the Paul Dyck Collection to the Plains Indian Museum ensures these exceptional objects will be preserved, and the collection will remain intact for current and future generations of Native Americans and others with interests in Plains Indian art and cultures.”

In addition to caring for the collection, there were long range goals of a permanent special exhibition gallery in the Plains Indian Museum devoted solely to the collection, a traveling exhibition, and a catalogue. Before any of this could be achieved, however, Center staff had to provide for the collection’s most basic necessities. It needed to be unpacked and safely settled into its new home. With such a massive and varied collection came the challenge of unraveling the complexities of objects through systematically unpacking, accessioning, documenting, treating, and storing each, a process that has taken place over the past four years.

The richness and depth of the Paul Dyck Collection is apparent in its diversity. The collection contains objects representing every Plains tribe, and a staggering range of dates (early nineteenth to twentieth century), artists, and materials. Some compared the situation to a hospital triage to “treat” or process the collection.

First, staff cared for objects in need of immediate attention due to the object’s age and often delicate condition. Each “patient” had a different size, age, and material makeup with strengths and weaknesses. Once an object received care, there were many others that needed help, too. An inventory of the collection was completed prior to its move to Cody—and each box, bin, or trunk held its own mysteries until objects were gently exposed and unwrapped to begin their formal introduction into the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West]’s collection database.

Many objects offered basic clues as to their origins and use, but had little detail about the maker, wearer, exact dates, and their composition of materials. Some gave up their history more easily with distinctive designs, beadwork patterns, or materials—even old object tags on a good day.

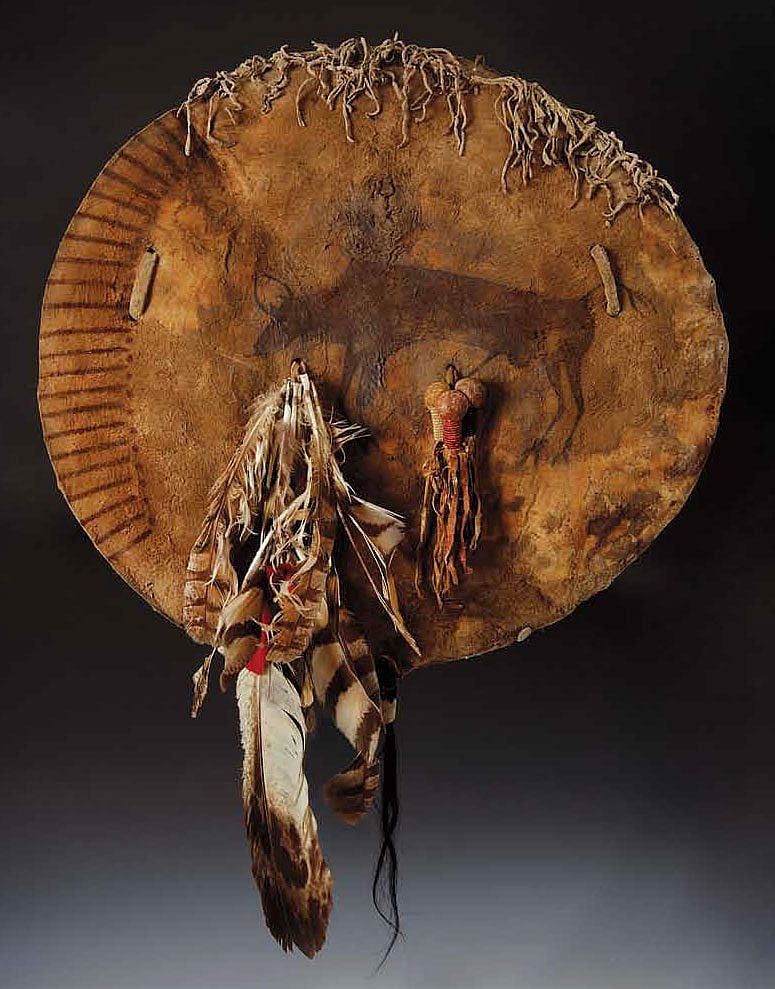

Humped Wolf’s shield, lifted from Locker #23 on June 5, 2009, is one such example of an extraordinary piece that offers an enticing glimpse into the power and story behind its creation.

Humped Wolf’s Shield

By Anne Marie Shriver

It looked familiar: The minute I opened the old foot locker and gently unwrapped it; I knew I had seen it before, this remarkable bison painted on the front of a very old shield.

Even with all the books I perused through the years, this bold image had stood out in my mind. Looking through an old exhibition catalogue, I spot the bison shield, but the one in front of me is, well…even better. My job is unbelievable.

Decorations on shields (mínnatse in the Crow language) are revealed to men in dreams and visions, and are among the most individual type of expression in Plains art. The protective quality of the decorated shield was innately attributed to this supernatural experience, and men going into battle wanted to carry one. Every shield has its own story and, fortunately, anthropologist Robert Lowie of the American Museum of Natural History recorded the narrative of this particular shield in the early twentieth century.

When he was 18 years old, Humped Wolf was part of an Apsáalooke (Crow) war party. When they had gone a great distance, they were attacked and many Crow were killed. Humped Wolf was shot through the legs above his knees, but was still able to travel with the other survivors. He became separated in a snow storm and, wandering across the prairie, he thought he was going to die—when he came across a big black object, a dead buffalo. He took shelter inside it and was about to fall asleep, when the buffalo snorted; he then received his vision. Eventually, Humped Wolf found his way back to camp to the surprise of the others, who thought him dead.

When he arrived, he summoned all the older men to his tipi and told them his vision. He described it and told them he liked it.

“Make it,” they said.

Conceivably, this version of Humped Wolf’s shield from the Paul Dyck Collection may be even more precious and powerful because of what we first thought of as a flaw or condition defect. But during cleaning, we discovered something even more fascinating.

the round mark above the painted bison in the shield detail image. Thanks to collaboration with [former] Draper Natural History Museum Assistant Curator Philip McClinton, we determined the mark to be an old, healed-over wound on the bison. When the bison was later killed and its hide used to create the shield, almost certainly that particular spot from the bison’s hump was chosen to reflect the power, strength, and endurance of the bison and shield—traits transferred to the owner/artist. Just a theory, but…

The owl feathers attached beneath the painted bison possibly provided the ability to see in the dark, and move silently and unnoticed. The golden eagle feathers perhaps gave its owner the swiftness and courage of that bird. The dark lines on the left side represent the bullets or arrows the shield helps repel.

All shields were cared for in specific ways to preserve their protective powers. Humped Wolf’s shield could never be placed on the ground. When Humped Wolf was travelling and needed rest, he placed it on a sagebrush.

Crow ceremonial objects were sometimes made in as many as four versions and presented to the owner’s relatives. There are two other versions of Humped Wolf’s shield—one in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the other at the National Museum of the American Indian.

Shields made by nineteenth century warriors still carry the inherent powers of their owners and their spiritual protectors. Such shields now held in museum and private collections are treated—as are all collections objects—with great respect.

Each item in the Paul Dyck Plains Indian Buffalo Culture Collection delivers a quiet message: respect for times past and knowledge for future generations of Native people to help them better see and understand where they came from—and where they are going.

About the authors

Anne Marie Shriver is the research associate for the Dyck Collection and serves as the “Save America’s Treasures” grant project manager.

Rebecca West is the assistant curator at the Center’s Plains Indian Museum.

About the collection

The Paul Dyck Plains Indian Buffalo Culture Collection was acquired through the generosity of the Dyck family and additional gifts of the Nielson Family and the Estate of Margaret S. Coe. Additional funding from “Save America’s Treasures”—administered by the U.S. National Park Service—makes the collection accessible to researchers, tribal members, and scholars, and improves storage conditions for its care and preservation. Thank you!

Post 056

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.