All That Slithers, Reptiles of the Greater Yellowstone Region – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2008

All that slithers is not so terrible after all: Reptiles of the Greater Yellowstone region

By Philip and Susan McClinton

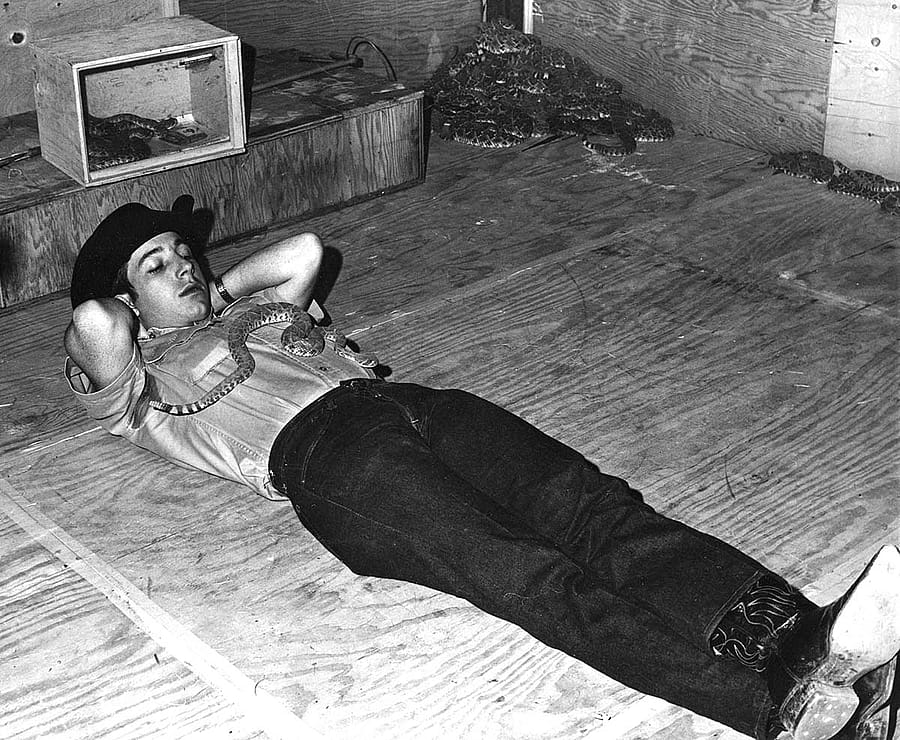

We’d searched in Oregon Basin all day on one of the first warm days of April 2007, looking for some sign of the prairie rattlesnake, Crotalis viridis viridis—locally known as the western rattlesnake. Now in the waning daylight, we’d almost given up hope of finding one for a live presentation I was to conduct in the Draper Natural History Museum that month. I told myself “just one more rock outcropping” and my wife, Susan, tired from the day’s climbing, crossed the coulee and started the hike back to the truck.

Keeping the hand mirror we used to shine under rocks to provide illumination in the dark recesses where the snakes hide, I said I’d flash the mirror if I found anything. As I rounded a sharp outcrop of the crumbling sandstone rock, I spied a flat rock about the size of a garbage can lid jutting out from the hillside. It was just about the right size for a rattler to take refuge under and on the correct side of the hill—facing southwest, where a rattler could take advantage of the warming rays of sunshine.

The mirror caught the last rays of sunlight and instantly brought light to the dark space under the rock. And there, curled up just out of the fading light and in among prickly pear spines, was a small rattler about a foot and a half long. Excited by the find at the very end of the day, I flashed the mirror at Susan, and she made her way hurriedly back up the hill to see what I’d found. Later christened “Miss Snake” (gender confirmed by a visual and gentle examination of the vent area), she was to make her debut at the first live rattlesnake presentation in the Draper Museum. After the presentation, we returned Miss Snake unharmed to the exact location where she was captured and freed her.

A lifelong fascination with reptiles and amphibians has most recently allowed me to share valuable information about some of nature’s most misunderstood animals—snakes, lizards, and amphibians—with children and adults in the Greater Yellowstone region.

Snake opened up a world of possibilities to more than two hundred school children who attended the two-day presentation at the Draper Museum in April 2007 and dispelled some myths held about snakes. For example, while it is true that rattlesnakes, in particular, are dangerous, they, like many other animals, would rather avoid contact with humans. They prefer to slither away undetected rather than risk an encounter with a species many times their size.

Due to the elevation and northern latitude of the Greater Yellowstone region, only one species of rattlesnake lives here. The aforementioned Crotalis viridis viridis ranges from Canada south to Mexico and from California to the Mississippi River. It is found at elevations up to 9,000 feet and can be discovered in a variety of habitats including woodlands, scrub areas, prairie grasslands, sand dunes, and rocky outcroppings that afford a southern exposure. Many rattlesnakes will take up residence in prairie dog towns for the summer months; caution should be exercised when visiting such areas.

Seeing, hearing, tasting

Prairie rattlers are pit vipers—so named for the two “pits” located behind the nostrils which allow the snake to be able to detect the heat “signature” of an animal. This pit allows the rattler to detect as little as a one quarter degree Fahrenheit rise in temperature. They can detect a lighted candle from thirty feet away, which enables them to hunt, or defend themselves, in total darkness.

Every snake has a specialized organ, Jacobsen’s organ, in the roof of its mouth. This allows the snake to “taste” an odor by quickly flicking the tongue in and out of its mouth, catching the odor molecules. Then it inserts its tongue tip into the Jacobson’s organ for identification. Humans can achieve much the same effect by inhaling through their nose with their mouth open thus “tasting,” for example, the smell of chocolate chip cookies.

Snakes of all types lack ears. They cannot hear sounds, but they do pick up vibrations in their environment from both the ground and air through various parts of their bodies. In addition, natural selection has provided prairie rattlers with a marvelous camouflage pattern of blotches on the back usually with a dusty light brown, yellowish, or gray green background color, which makes them very difficult to see. Some grow to lengths of up to four feet and weigh as much as two pounds or more.

Contrary to popular belief, snakes are not actually slimy, but are smooth (almost silky), dry, and cool to the touch. Plus, a rattlesnake’s age isn’t determined by counting the rattles at the end of its tail. These rattles are retained each time a rattler sheds its skin, and that occurrence varies according to the availability and abundance of prey. The better fed a rattler, the more times it sheds its skin, and the more rattles it retains. By rattling, a rattlesnake is saying, “I’ve been seen, and I’m in danger.” This is the snake’s fear response. The rattles are used as a warning not to venture too close. Just like people, some rattlers are mild-mannered; some are not.

The primary constituents of the prairie rattler’s diet are mice, but they will also consume young rabbits, ground squirrels, and chipmunks. Lizards, frogs, toads, and occasionally birds are also included in their diet. Two curved fangs are folded back into the roof of a rattlesnake’s mouth when not in use. These fangs are hollow, and muscles squeeze the venom from the venom sacks into these fangs and into the victim during the bite. Their venom is hemotoxic; that is, it ruptures blood cells in the body. To small mammals, the bite from a prairie rattler is fatal within minutes. The venom not only kills the prey but aids in the digestion as well. The jaws are actually hinged to allow for swallowing prey that is larger than the rattlesnake. Prey is ingested headfirst and may take several days to digest fully.

All snakes are exothermic, i.e. cold-blooded, and depend on the ambient temperature or sunshine to warm their bodies. They must also seek shade during very hot weather to cool themselves. Extreme heat will kill a snake, and when temperatures decline in the winter, it enters a state of hibernation. Winter is spent in a deep, protected space beneath rocks or similar substrate in what is referred to as a hibernaculum. Most snakes will stay within two to three miles of the hibernaculum, which is also used by other reptiles and sometimes mammals and insects. Rattlers can, however, travel distances of up to five miles in search of prey. On sunny days in the spring, they may rouse and come to the entrance of their “den” to sun themselves. They do not fully emerge until temperatures climb sufficiently, and stabilize, to raise their body temperature.

Snakes are tetrapods and are descended from vertebrates with four limbs. The majority of snakes are egg layers (oviparous), but numerous species give live birth. In the case of live birth, eggs are either retained in the body (ovoviviparity), or no calcified egg is produced (viviparity). The majority of snakes have three-chambered hearts and breathe air. Most reptiles reproduce sexually, although some reproduce asexually (parthenogenesis). Snakes travel by rhythmic movement of their muscles, and the scales covering the skin aid in “gripping” the substrate. Snakes also have an extendable trachea (windpipe) similar to a fleshy straw that enables them to breathe while swallowing their prey.

Rattlesnakes breed in the spring and give live birth to their young (usually between seven and twelve young in a clutch or delivery) which are generally six to twelve inches in length. The young are precocious—fully functional at birth—and, until recently, female rattlers were thought to take no interest in their offspring. In some species, however, scientists have discovered that the female rattlesnake stays with her young until after their first shed. The young rattlers feed on insects and small lizards until they are large enough to feed on rodents.

Males have hemi-penes (double penis), which protrude from the vent area when gentle pressure is applied, making determining gender relatively easy, but hazardous, considering their lack of patience at being handled.

Other Yellowstone snakes

The Greater Yellowstone region is also home to five other snake species of lesser reputation than the prairie rattlesnake: the valley and intermountain wandering garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis fitchi and Thamnophis elegans vagrans, respectively); the bullsnake (Pituophis catenifer sayi); the rubber boa (Charina bottae); and the pale milk snake (Lampropeltis triangulum multistriata). Bullsnakes, milk snakes, and rubber boas are constrictors; that is, they suffocate their prey by squeezing until the victim is unable to breathe. All snakes have small teeth, relative to their size, to aid in holding their prey.

Both species of garter snakes prefer riparian habitats with the valley variety preferring permanent surface water, and the intermountain wandering variety usually found near water. When frightened, valley garter snakes will retreat to the water, while intermountain wandering garter snakes prefer sheltering in dense plant cover. The diet of the valley garter snake is narrower in scope and includes earthworms, fish, toads, and chorus frogs, and they can eat relatively poisonous species of animals. Intermountain wandering garter snakes feed on frogs, tadpoles, fish, salamanders, earthworms, small rodents, leeches, snails, and slugs.

The valley garter snake is the larger of the two species and can reach a length of up to thirty-four inches. The intermountain wandering garter snake usually doesn’t exceed thirty inches in length. Coloration varies between the two species. The intermountain wandering garter snake is brown, brownish green, or gray with three light stripes, a stripe on each side and one the length of the back; the valley garter snake is nearly all black with three bright, longitudinal stripes running the length of the body and an underside of pale yellow or bluish gray. Irregular red splotches along the side complete its vivid coloration. Both species are generally diurnal (active during the day) and can give live birth to as many as twenty young during the summer months. Finally, both may exude a foul smelling musk from glands at the base of the tail when threatened, making handling them a particularly distasteful task.

The bullsnake of the Greater Yellowstone region is a subspecies of gopher snake and is the largest reptile in the area. This snake can easily reach seventy-two inches long and has distinctive markings. Coloration is mainly yellowish with reddish-brown, black, or brown splotches down the back with the darkest colors near the tail and head. They have a dark band that extends through the eye to the lower jaw area and a protruding scale at the end of the nose. They lay one or two clutches of two to twenty-four eggs during the summer months.

Like the prairie rattlesnake, bullsnakes prefer warmer and drier open habitat areas. They are burrow dwellers, and their diet consists mainly of small rodents such as gophers (hence one of their common names, the gopher snake), rats, mice, and occasionally rattlesnakes. They are masters of mimicry and are often mistaken for the prairie rattler by hissing, coiling, and vibrating their tail against the ground to produce a rattling sound.

Rubber boas are nocturnal (active only at night) and are rare in the Greater Yellowstone region. They are related to the pythons and boa constrictors and can reach a length of up to twenty-three inches. The belly is usually yellow with a brown or gray back. Rubber boas have very small scales and are very soft to the touch. They bear live young (two to four usually) from August through November. They prefer rocky habitat near rivers or streams and are often found buried in leaves and/or soil with trees and/or shrubs close by, or in rodent burrows. Their primary prey is rodents.

Milk snakes derive their common name from their habit of frequenting barnyards to hunt mice and have been mistakenly accused of “milking” cows. They are very often nocturnal and are secretive, preferring places such as rotting logs or under rocks. They feed on a variety of small mammals, birds and their eggs, reptile eggs, and lizards. Their clutches usually contain from two to seventeen eggs and are laid during the summer months.

Slithering into fact, myth, and history

All snakes and lizards shed their skin, which results in a condition sometimes referred to as “in blue”—so called because of the bluish, opaque appearance the old skin exhibits before it’s shed. The eyes in particular give this bluish opaque appearance, and reptiles, especially snakes, become agitated much more quickly while they are shedding because the old skin limits their vision. Lizards shed their old skin in pieces while snakes normally shed their old skin in one continuous piece. After shedding, the animal’s colors are most vivid.

Snakes have been vilified throughout history, from the story of the serpent speaking to Eve and encouraging her to eat the forbidden fruit, to the often-held modern opinion that the only good snake is a dead snake. Taken individually, the contribution of an individual species may be viewed as small. On the whole, however, snakes provide a very valuable service to humans by ridding the environment of excess mammals and insects that potentially carry diseases or damage food crops. Because some of the natural history of snakes may be poorly known or understood, there could be aspects of their actual contribution to the environment that may be undiscovered or obscure. Certainly the intrinsic and aesthetic value of snakes plays well in our world.

Snakes are fascinating animals that mesmerize us and remind us that reptiles have been around for many millions of years, surviving extinction and continuing to evolve toward the “perfect” reptile. Many have remained virtually unchanged for millennia. Modern reptiles occupy every continent except Antarctica. In the Greater Yellowstone region, even the casual visitor can add to the body of knowledge about the distribution and abundance of reptiles.

Much remains to be learned about reptiles in this area. Small and large, they continue to pique our interest, to generate feelings of awe and sometimes fear, and to remind us that they too contribute to the spectacular natural beauty that is the Greater Yellowstone region.

About the authors

Philip L. McClinton is the former curatorial assistant for the Draper Natural History McClinton. Susan F. McClinton has served as an information and education specialist on grizzly bears for the Shoshone National Forest in Cody, Wyoming, and as a teacher-trainer for Eleutian Technology in Powell, Wyoming. Each holds an MS degree in biology from Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas, and both have a keen interest in animal behavior, conservation, and wildlife education—especially in that which takes place in the natural environment. Both McClintons have conducted extensive research on black bears; mountain lions; white-winged, mourning, and Inca doves; and parasite/host interactions in nature. The McClintons have published and presented a number of articles and reports about their work.

Post 059

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.