The Art of Beadwork – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2004

The Art of Beadwork: An Old But New Tradition

By Emma Hansen

Curator Emerita and Senior Scholar, Plains Indian Museum

Visitors to the Plains Indian Museum are often fascinated by the skill, creativity, and diversity of beadwork artists represented in the galleries. They are also interested in learning about the historical development of beadwork traditions among Plains Indian people—traditions that for many people are symbolic of all American Indian art forms. While appreciating the array of beadwork from the nineteenth and early twentieth century, as they are introduced to the museum’s growing collection of contemporary beadwork, visitors should also be reassured that the beadworking tradition is not only alive but is continually changing and being interpreted through the efforts of American Indian artists.

Although the use of glass beads by Native beadwork artists became prevalent as an art form about 150 years ago, manufacturing of beads from natural materials is an age-old tradition in North America and is evidenced by small stone and bone beads found in archaeological sites dating back more than 10,000 years. Prior to the arrival of trade beads, a variety of natural materials were used to make beads in Native North America, including shells, stones, teeth, ivory, wood, and seeds. Columbus and other early explorers to the Americas brought bead—lightweight, popular, and profitable trade items—as did Lewis and Clark and other Euro-American trade and diplomatic expeditions that traveled through the Plains, Plateau, and other regions. European-manufactured beads were exchanged for hides, surplus foods, and other materials through long-established Native trading networks and at centers of trade such as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara villages along the Upper Missouri River.

By 1850, Native people of the Plains and Plateau were eager to acquire glass beads and began incorporating them into their artistic works through experimentation with novel techniques and designs made possible by the new medium. Initially sewn with deer and other animal sinew and later with cotton thread, beads were used to decorate clothing, tipi bags, and other furnishings, and horse blankets and other equipment. In some cases, beads replaced natural materials such as porcupine quills or painted pigments. In other cases, more elaborate designs were created as beads were used in combination with older materials.

During the early reservation period of 1880 to 1920, beadwork arts flourished as culturally distinctive designs were developed among Plains and Plateau peoples. Besides being an artistic outlet and means of expression for women, the creation of beaded items for sale to museums, collectors, and tourists traveling through their reservations brought in much needed income for the family. The creation of beaded items for personal and family use at ceremonies, parades, powwows, and other celebrations helped to maintain tribal cultural identities and brought individual recognition for their artistry.

Contemporary beadwork artists continue to create for family and personal use for powwows and other celebrations as well as for income. Although most beadwork artists are women, men are also working in this medium more frequently. Traditionally, beadwork skills and designs have been learned within family settings, although this art form is now more formally taught through tribal and cultural programs on reservations and in urban areas and in art programs in high schools and tribal colleges.

Three beadwork artists represented in the Plains Indian Museum collection are Wilma Jean McAdams-Swallow, Vivian Swallow, and Sandra Swallow-Hunter. These Eastern Shoshone tribal members from the Wind River Reservation excel in the creation of traditional Shoshone dance clothing. Descendants of Sacagawea’s family and Chief Washakie’s youngest son, Charles, who served on the Shoshone Business Council for many years, the women state that their family is dedicated to preserving Eastern Shoshone art forms and traditions.

Vivian Swallow and Sandra Swallow-Hunter learned beadwork from their mother, Wilma Jean McAdams-Swallow, who has beaded for more than thirty years. A retired rancher from the area of Crowheart, Wyoming, Wilma Jean McAdams-Swallow is a Golden Age traditional dancer at local powwows. She was active in promoting the arts of the Wind River Reservation in the 1970s through the Shoshone and Arapaho Artists Association and is known for making Shoshone-style moccasins, belts, and dresses.

Vivian Swallow remembers that she began working with beads as a small child by stringing together beads of mixed colors remaining from her mother’s work. By her late teens, she began working on her own projects. According to Sandra Swallow-Hunter, the three women began designing dresses when her mother and sister decided to return to powwow dancing. They found that it was difficult to find an Eastern Shoshone tribal member who actively designed and made hide dresses for powwows and other celebrations. Most tribal members have one or two buckskin dresses that have been handed down from one generation to another. According to Sandra Swallow-Hunter, “We realized that the art of buckskin dress making, like saddle making, is nearly gone. We decided that we would make our dresses in order to inspire the many talented Eastern Shoshone artists to revive the art. We work on each dress as a team; each of us has our own strengths and contributions to lend to each dress we make.”[1]

Like the dress and woman’s moccasins in the Plains Indian Museum collection, much of the clothing and accouterments made by this family of beadwork artists features the distinctive Shoshone rose design. Since World War II, the rose has become one of the dominant and most recognizable patterns used by Shoshone artists. Vivian Swallow affirms that at powwows one can often distinguish Shoshone tribal members by the roses on their dance clothing. Although Crow bead artists also have rose patterns, the beading technique is different from that of the Shoshone and tends to follow straight lines rather than the shape of the rose petals and leaves. Vivian Swallow describes the Shoshone preference for the rose and other natural designs in the following way: “The Shoshone, like other Native Americans, use elements that surround us, like the mountains seen as geometric designs on our moccasins. Roses are something beautiful in nature, which surrounds us. Originally, we used the wild rose, but after the Shoshone were exposed to embroidery through the boarding schools, we began making more elaborate designs.”[2]

In addition to Shoshone style dresses featuring the rose design, Sandra Swallow-Hunter also makes fully beaded dresses, similar to those worn by Shoshone Bannock women, for family and other tribal members who compete in major powwow dance contests. She has not3ed that a dancer without a fully beaded dress often would not be noticed in such large powwow arenas.[3] She also makes traditional trade cloth dresses, jingle dresses, and other accessories.

Sandra Swallow-Hunter, her sister, and mother remain active in many reservation activities and programs—such as the One Shot Antelope Hunt—and tribal organizations. Sandra Swallow-Hunter works as the Tribal Funds Manager at the Bureau of Indian Affairs office in Billings, Montana; and Vivian Swallow works for the Indian Health Service on the Wind River Reservation, while serving on the Eastern Shoshone Housing Board and the Veterans War Memorial Committee. Both women are currently pursuing Masters of Public Administration degrees. They have taught beadwork classes to Eastern Shoshone tribal members and demonstrated their art in public venues such as the Plains Indian Museum. In a particularly interesting project a few years ago when Vivian Swallow worked as the Eastern Shoshone Child Welfare Specialist, the two women taught a class on parenting that featured cradle making. More recently, Sandra Swallow-Hunter made a Shoshone style cradle for her own daughter born in November 2003.

The vest in the Museum’s collection created by Shoshone Bannock artist Debra Lee Stone Jay shows a different approach to the use of the Shoshone rose design. The vest is made of smoked tanned hide, which provides a soft brown color as background for the beadwork and features a combination of Shoshone geometric designs and the rose pattern.

Debra Lee Stone Jay comes from the Shoshone Bannock Reservation at Fort Hall, Idaho, where she still lives. She is a Shoshone Bannock tribal member, also of Paiute descent, whose family has great respect for tribal traditions. “Our family was raised in the traditional manner with all the language, customs, and traditions of the tribe. Our grandmother was known as a master in the art of hide tanning and beadwork specializing in intricate floral and geometric designs of the intermountain tribes. Our grandfather also helped us by telling us about the colors of the sky and the animals, explaining to us about the markings and the movements of certain wildlife. Our grandparents were very great people to our family.”[4]

Debra Lee Stone Jay creates fully and partially beaded dresses, vests, moccasins, cradles, purses, and other accessories featuring distinctive floral, geometric, and animal designs as well as portraits of Shoshone Bannock people. In addition to crediting her grandparents for their encouragement regarding her beadwork, she also recognizes the influence of Shoshone Bannock artist Clyde Hall, whom she considers her mentor.

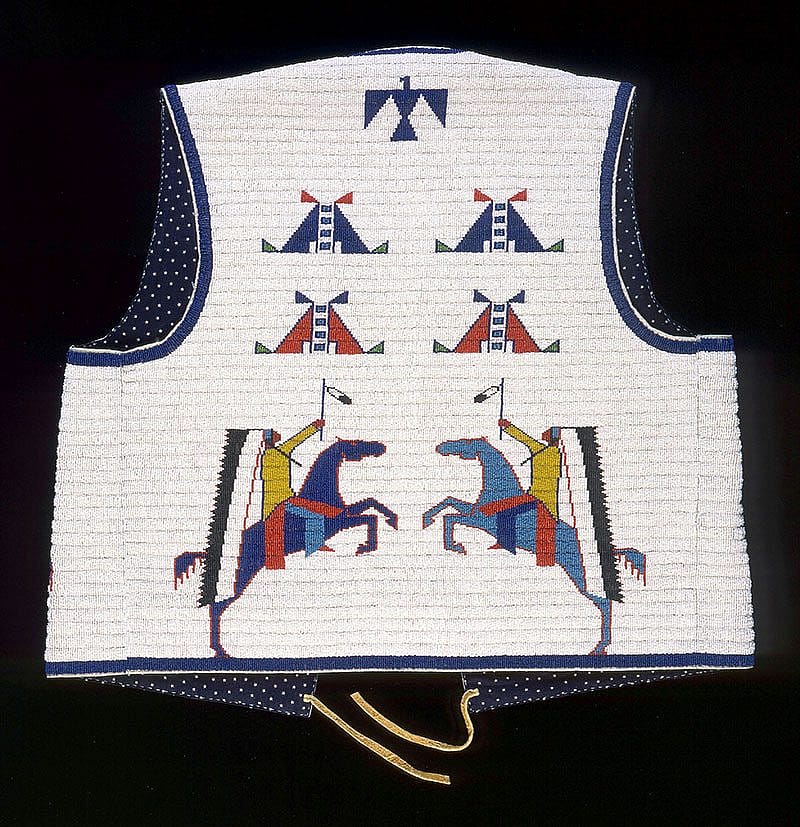

Man’s Vest (front), Marcus Dewey, Northern Arapaho. NA.202.1276

Man’s Vest (back), Marcus Dewey, Northern Arapaho. NA.202.1276

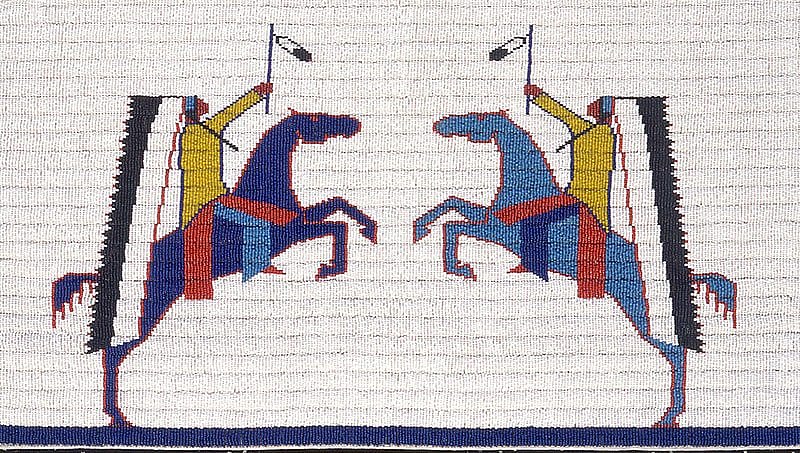

Man’s Vest (detail, back), Marcus Dewey, Northern Arapaho, Fort Collins, Colorado, 2003. Tanned hide, glass beads, and cotton cloth. Plains lndian Museum Acquisitions Fund Purchase. NA.202.1276

Another contemporary beadwork artist represented in the Plains Indian Museum collection is Marcus Dewey of the Northern Arapaho Tribe of the Wind River Reservation. Marcus Dewey is known by Native American art specialists and collectors for his distinctive beaded saddles. He uses McClellan military saddles—standard issue saddles from the time of the Indian Wars until World War I—as the foundation for his beadwork designs featuring traditional Arapaho colors of white, blue, red, and yellow. The saddle in the Plains Indian Museum collections combines pictographic images of a young buffalo and its mother on each side with symbolic representations of buffalo tracks. The beadwork on the saddle is accented with blue and red wool cloth and brass tacks.

The vest made by Marcus Dewey in the Museum’s collection is reminiscent of the fully beaded Northern Plains men’s vests of the early reservation period. During this period, women began to illustrate men’s deeds through pictographic beadwork designs on clothing, pipe bags, and other objects. Men’s vests—with pictorial designs of warriors, horses, buffalo, deer, elk, cowboys, and often the American flag—were worn by Northern Plains men for powwows, parades, and other celebrations or sold to non-Indians. The vest pictured on these pages features tipi and thunderbird designs with two facing warriors on horseback on the front and back. The warriors wear eagle feather bonnets with long trailers and variously hold shields, coup sticks, a tomahawk, and lance.

Marcus Dewey does historical research and consults with older family members as he develops his designs, but he states that many of his designs come to him when he is sleeping. In addition to the saddles and vests, he makes fully beaded Arapaho-style cradles.

For Northern Arapaho, Eastern Shoshone, and Shoshone Bannock people, beadwork is a longstanding tradition that did not end when major museum collections were assembled at the beginning of the twentieth century. The contemporary beadworkers represented in the Plains Indian Museum collections, like Native artists elsewhere, look to their antecedents for inspiration while continually experimenting and incorporating their new ideas and experiences into tribal designs and traditions.

1. Sandra Swallow-Hunter, correspondence, November 22, 1999.

2. Vivian Swallow, phone interview, March 15, 2004.

3. Sandra Swallow-Hunter, November 22, 1999.

4. Debra Stone Jay, correspondence, February 11, 2003.

Post 064

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.