Great Britain Gets a Visit from an Indian Princess and Her Husband – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2012

Great Britain Gets a Visit from an Indian Princess and Her Husband

By Tom F. Cunningham

At the same time that Buffalo Bill was in England in 1887, congregations in the United Kingdom also heard about America, specifically the plight of its Indian tribes, through a young Indian woman known as “Bright Eyes,” along with her activist husband. Here, Scottish author Tom Cunningham captures the essence of their tour of the United Kingdom.

On August 20, 1887, the “American Exhibition—Buffalo Bill” was proving to be the sensation of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year. Sharp-eyed readers of London’s Pall Mall Gazette no doubt observed that this was not the sole Native American presence in London highlighted in that day’s attractions column. For at the Great Assembly Hall on the Mile End Road, it was billed that, “Mrs T. Tibbles (‘Brighteyes’) will lecture on Indian Life.”

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, with the aid of scores of Lakota Indians, cowboys, and Mexicans, engaged in the work of spectacularly re-enacting the defining episodes of the epic of conquest of the American West. In his Wild West show, he presented the process of western expansion as a heroic, salutary endeavor in which savagery was by stages supplanted with civilization.

Simultaneously, an educated and civilized Native American lady and her white husband labored to spread abroad their own tragic account of the same process, in a far less flamboyant and less conspicuous manner.

Susette La Flesche (1854–1903), also known by her Indian name of Bright Eyes, undertook an extensive lecture tour of Great Britain accompanied by her husband, an American named Thomas Henry Tibbles. For the most part, their lectures were delivered in churches affiliated with a variety of protestant denominations. Their mission was to proselytize in support of the cause of Indian citizenship and to endeavor to create a sympathetic awareness of the bleak conditions prevailing on the reservations.

Susette was the daughter of Iron Eye (Joseph La Flesche), the last principal chief of the Omaha tribe of Nebraska. He was known as one of the “progressives,” Native Americans who took a pragmatic approach in recognizing the hard reality that there was no turning back time. For better or worse, the progressives believed they were left with no alternative but to make their way, as best they could, in what was now irredeemably the white man’s world.

In the same way, Iron Eye’s daughter therefore made no plea for the retention of the old ways. Instead, Susette limited her aims to promoting conditions in which the Indians might participate in a grand synthesis of the races in as painless and all-embracing a manner as possible.

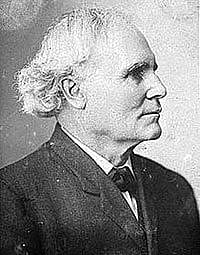

Thomas Henry Tibbles (1840–1928), several years his wife’s senior, was a man of conscience. In his youth, he spent time among the Omaha; had been personally associated with the liberationist John Brown of Harper’s Ferry fame; was a Methodist minister on the borderlands; and years later, in 1904, would stand as the unsuccessful Populist candidate for Vice-President of the United States.

However, the zenith of his career as the conscience of the frontier came in 1879. As a crusading newspaper editor in the town of Omaha, Nebraska, Tibbles greatly publicized the plight of a dispossessed and fugitive fragment of the Ponca tribe who had been subjected to military arrest after taking refuge on the reservation of the Omaha to whom they were closely related. Tibbles then successfully coordinated a campaign to bring the landmark civil rights case of Standing Bear v. Crook before the federal courts in 1879. The court upheld the view that Indians were “persons” in the eyes of the law and that the remedy of habeas corpus was therefore open to them.

After the case, a party of four—Tibbles, Standing Bear himself, Bright Eyes as his interpreter, and her brother Frank, also known as Woodworker, traveling as his sister’s chaperone—toured the lecture circuits of the eastern United States, seeking to build upon their earlier success by keeping the plight of the Ponca, the Omaha (now themselves threatened with removal), and recently-conquered native nations generally in the public eye.

Following the sudden death of his wife, Tibbles and Bright Eyes subsequently became romantically involved and eventually married. Standing Bear never toured again, but Tibbles and Bright Eyes continued to fly the flag. They campaigned in the East for several years, proving themselves effective lobbyists capable of exerting a powerful influence on the actual course of events. A logical progression, similar to what had impelled Buffalo Bill across the Atlantic, next took them to Great Britain in order to seek support for their cause there, too. A number of British newspaper articles chronicled the visit of Tibbles and Bright Eyes to England. For example, the July 30, 1887, issue of the Blackburn Standard (Blackburn, Lancashire, England) was one of several journals that published a syndicated story about the couple’s cause:

The curious spectacle of a member of a tribe of Indians preaching Christianity to an English congregation was witnessed on Sunday evening, when the daughter of the chief of the Omahas, known through the States as “Bright Eyes,” with her husband (Mr. Tibbles), conducted special service at Hare Court Chapel, London.

The Pall Mall Gazette of August 2, 1887, published an article with a line drawing of the couple and the following elucidation of their mission:

They will tell of Indian life before it was hedged in and harassed by civilization, and when there were fierce inter-tribal wars; of the domestic life and the social and religious customs of Indians; of their unwritten literature and their traditions; of their terrible experiences, as white men occupied the old hunting-grounds and drove the red men before them, not caring what became of them. It is a strange, picturesque, sad history, full of interest, of dramatic scenes of tragedy and of wild beauty.

By the middle of September 1887, the couple turned their attentions to Scotland, where they solicited invitations to present the message of the Indian Citizenship Society before congregations in the Glasgow area. A long-winded and mildly ridiculous article appearing in the Glasgow Herald on September 19 went somewhat overboard on the royal status to which Susette was ostensibly entitled. By virtue of being a daughter of the Chief of the Omaha, the story delineated her in such phrases as “a veritable scion of a Royal stock” and “a genuine Princess,” going so far as to draw the corollary that Tibbles ought properly to be referred to as her “Consort” and her agent as “Prime Minister.”

Later, in an interview appearing in the Pall Mall Gazette September 26, 1887, Tibbles stated that he had brought the concerns of the Aborigines Protection Society regarding the deteriorating conditions in Canada, where wrongs had been inflicted upon the Indian tribes in the name of the laws and government of the United Kingdom.

Tibbles opined that summary confiscations of land by the minority white population of British Columbia had left the Indians with just sixty thousand acres from a total acreage of about two and a half million. He also demanded the abolition of the reservation system, saying that the Indians should instead be placed upon an equal legal footing with whites. Instead of being a protection to them, confinement on the reservations kept the Indians in a perpetual state of misery and degradation, and isolated them from all progressive influences.

On January 8, 1888, Tibbles and Bright Eyes appeared at the Gilcomston Free Church in Aberdeen, Scotland—a crowded facility with a seating capacity of twelve hundred. There Tibbles described the character of the American Indian as having been entirely misrepresented. Refuting the fallacy that the Indians were racially inferior and therefore incapable of civilization, he discussed the need for renewed missionary endeavor. He passed on the words of a chief who had remarked to him that the Indians had advanced further in the past fifty years than the Anglo-Saxons had in a thousand.

Next, Susette ascended the pulpit and outlined the principal incidents of her childhood and early career. The Aberdeen Journal (January 9, 1888) captured the essence of this address:

The time had come when her people must give way; civilization was pushing them. They saw themselves as a nation melting away, and what was to become of them they did not know. Bright Eyes held that the only hope was to bring them under the power of civilization and the influence of the Gospel.

After that, Tibbles developed the argument that the entirety of economic advantages derived by the people of Great Britain from trade with North America, were received by virtue of lands which had been taken forcibly from their original owners, the Indians, without recompense. Consequently, there was a reciprocal obligation to send the blessings of the gospel and the influences of civilization among the Indians, as the means of enabling them to continue in existence.

The next month, on February 24, 1888, another British newspaper, the Newcastle Weekly Courant, carried a report with the arresting heading, “An Indian Squaw at the Central Hall.” The newspaper observed that Tibbles and Bright Eyes had “attracted considerable and perhaps curious attention, both as regards their important mission and peculiar personal history.” The article also commented on the success which the couple had enjoyed in campaigning for the temperance movement.

By the winter of 1890, Tibbles and Susette had returned to America and were present on the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, at the time of the infamous Wounded Knee massacre. In fact, Tibbles’s body of work on the subject, in which he exonerated the Indians of all blame for the tragedy, was several generations ahead of its time for its enlightened and sympathetic perspective. After their return to the States, the couple continued to actively write and lecture on behalf of the rights of Native Americans.

About the author

Of Scottish descent, Tom Cunningham is a graduate of Glasgow University in Scotland. Because of health issues, he now has what he calls “many hours of enforced leisure,” using the last two decades to pursue an intensive study of Native American history with particular emphasis upon connections with Scotland. He is the author of The Diamond’s Ace—Scotland and the Native Americans, and Your Fathers the Ghosts—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Scotland. Cunningham has conducted extensive research at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Post 068

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.