Feeding Cowboys in the Days of the Open Range – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2005

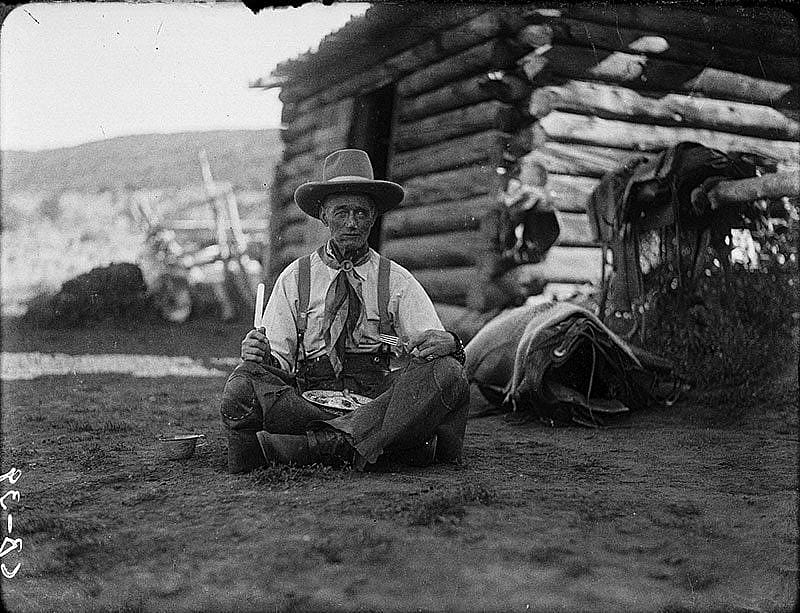

Feeding Cowboys in the Days of the Open Range

By B. Byron Price

Excerpted from his book, The Chuckwagon Cookbook—Recipes from the Ranch and Range for Today’s Kitchen, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Prior to 1870, a few basic staples dominated the menu in all cow camps. These included coffee, bread (in the form of biscuits, corn meal, or hard crackers), meat (bacon, salt pork, beef—fresh, dried, salted and smoked—and wild game), salt, and some sugar and sorghum molasses.

The quality and quantity of cowboy food depended on many variables including tradition, culture, region, sources of supply, the attitude of management, and the ability of the cook. Over the years Southwestern ranches gained a reputation as unimaginative and miserly in their fare, those on the Northern Plains as more progressive and generous. “Those Texas outfits,” recalled “Teddy Blue” Abbott with characteristic candor, “sure hated to give up on the grub.” Some supplied only flour, salt, and coffee, but most also allowed some salt pork or beef along with corn meal and sorghum molasses. In South Texas and parts of New Mexico, Arizona, and California, Mexican culinary traditions that included tortillas, fried beans, chile, chorizo (sausage), and rice dominated the range fare.

Abbott claimed that superior food, including cane sugar, wheat flour, canned fruit, and other “luxuries,” induced many Texans to remain in Montana long after their less particular comrades had departed for sunnier climes. Contrasting the lot of the Montana-based cowhand with that of his Southern Plains counterpart in 1885, a Dodge City, Kansas, newspaper correspondent concluded:

Live! Why, these cowboys [in Montana] live higher than anybody. They have every thing to eat that money can buy, and a cook with a paper cap on to prepare it. The cook is so neat and polite that you could eat him if you were right hungry…

Many observers believed that ranchers’ substantial profits would ultimately improve the cowboy’s menu. In 1877, for example, a Colorado newspaper commented:

The cowboy works for a man who has capital, is making great profits, and is naturally liberal in the use of money. The result is that there is plenty of food and a great enough variety… Fresh meats of the best quality they can have at any time, and canned fruits and vegetables are found at almost every camp. Coffee, syrup, sugar and tea are among the comforts found, while of the more substantial kind of food there is no lack in either quantity or quality.

Canned goods were reported in abundance on the Colorado range in 1883 and within a decade were available to even the most remote ranching outposts throughout the West. The flourishing American food processing industry continually expanded its offerings so that by 1885 a typical Spur Ranch supply order included, not only canned tomatoes and peaches, but also cinnamon, nutmeg, cayenne pepper, Coleman’s mustard, vanilla, and lemon extract. Meanwhile, the steady advance of the farmer’s frontier furthered the cause of fresh fruits and vegetables in ranch country, particularly among the largest and most progressive ranches.

Ranch provisions arrived from suppliers in tin cans, ceramic jugs, wooden boxes and barrels, and in sacks of paper and cloth. Not all of these stores reached their destination in first-class condition. In 1892, A.J. Majoribanks, owner of the Rocking Chair Ranch in Texas, struggled with spoiled flour and dried fruit, substandard molasses, and two cases of “very sorry” bacon, “about four-fifths being pure fat and waste.” In August, he complained to a supplier about rotten prunes:

The 53 pounds of prunes you lately sent us were more wormy than prunes; it is an outrage to try to put off such filthy stuff on us; we utterly refuse to receive or pay for such stuff and the said sack of prunes and worms have been left… to be returned to you…. It will save you a good deal of trouble if you will bear in mind that we will only receive and pay for articles that are good.

Although expenditures for food usually comprised the largest entries on ranch supply ledgers, the cost of feeding cowboys in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries appears nominal, costing only $1.32 per day or less than 4 cents per man for a meal. This figure seems consistent with a 1901 William Curry Holden survey of the records of the well-supplied Espuela Land and Cattle Company that revealed a single twelve-man cow outfit in 1889 devoured an estimated 19.2 pounds of food that placed the cost of comfortably providing subsistence for a cowboy at one dollar per week or 14.3 cents per day. By 1916, inflation had pushed the cost as high as 53.5 cents per man per day in some places.

The quantity and quality of the chuck wagon fare varied enormously—from excellent to awful. A cowboy working near the Red River in northern Texas during the 1880s perhaps spoke for the majority when he reported, “Our ‘chuck’ is substantial, but not aristocratically cooked.” Most considered range cuisine repetitious and bland, and some wondered how cowboys maintained their health with such “unvaried fare.”

One frontier settler speculated that outdoor work and riding the range helped keep cowboy digestive tracts in order. One recent study of the cowboy diet pronounced it deficient in vitamins A and C, calories and calcium—facts that no doubt account for the cowboy’s lean image. Calcium deficiencies, the result of a lack of milk, were blamed for bowlegs and bone decalcification—although long hours in saddle surely contributed to the condition.

Perhaps an 1885 story said it best with this mouthwatering comment:

The table was bare, the plates and cups were of tin, and the coffee was in a pot so black that night seemed day beside it. The meat was in a stewpan, and the milk was in a tin pail. The tomatoes were fresh from a can, and the biscuits were fresh from the oven. Delmonico never served a meal that was better relished. —from “The Cowboy as He Is,” Democratic Leader (Cheyenne, Wyoming), January 11, 1885.

About the author

Byron Price currently serves as the director of the Charles M. Russell Center For the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma, and director of the University of Oklahoma Press. He previously served as Executive Director of the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] and for the National Cowboy Hall of Fame (now the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum) in Oklahoma City. He is a prolific writer and speaker on the subject of the American West.

Post 069

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.