Is it a fake? An Art Museum Caper – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2007

Is it a fake? An Art Museum Caper

By Monique Westra

In 2003, the Glenbow Museum in Calgary embarked on an ambitious project to explore Charles M. Russell’s and Frederic Remington’s ties to the Canadian West: Capturing Western Legends: Russell and Remington’s Canadian Frontier, Glenbow Museum, June 19 – October 11, 2004. I was asked to create a more modest, adjunct exhibition drawn primarily from the Glenbow’s own collection. As I had long been intrigued with the amazing success of these two remarkable American western artists, I wanted to understand why their names are virtually synonymous with iconic images of the West. Clearly, a key factor in promoting and sustaining their great popularity was the widespread dissemination of their pictures through illustrations and reproductions.

Even after the deaths of Remington in 1909 and Russell in 1926, their visual monopoly on the “look” of the West continued in popular culture. But, as I was to discover, there can be a downside to fabulous commercial success: The huge and growing demand for the art of Russell and Remington brought with it a flood of fakes and forgeries.

The bad news

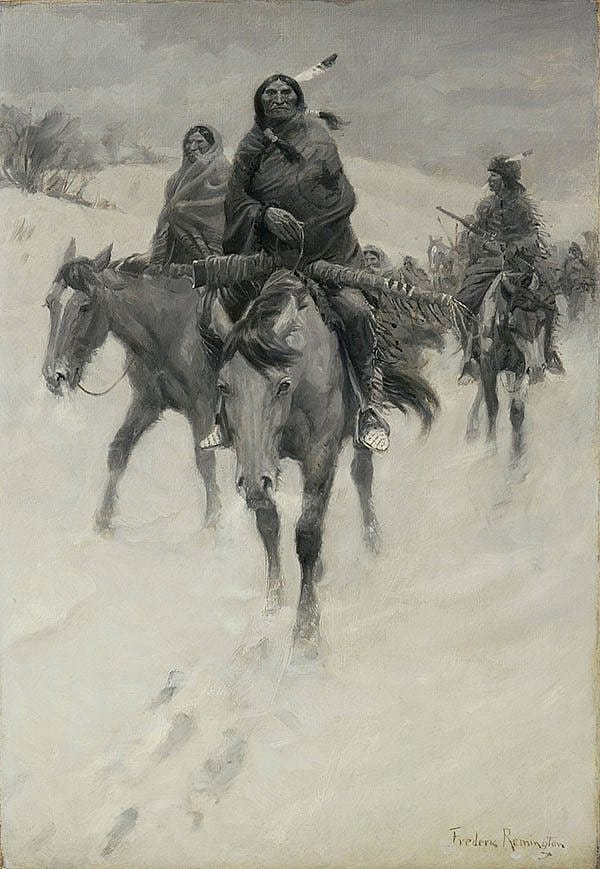

We at the Glenbow Museum had only one oil painting by Frederic Remington in our art collection. Titled Warriors’ Return, this undated painting was purchased in 1965 and, for almost 40 years, was considered to be one of the Museum’s treasures (illustration 1). But, when I consulted the Remington catalogue raisonné, a massive two-volume book that lists every known work by the artist, I was surprised to discover our painting was not included. Seeking an explanation for this omission, a digital image of Warriors’ Return was sent to Peter Hassrick, the book’s author and one of the foremost Remington scholars in the world. He responded that, in his opinion, Warriors’ Return was probably not a real Remington! Not a real Remington? How could I display a work in my show whose authenticity was in question?

In pondering this dilemma, I began to realize there was another way to approach this situation—not as a problem but as an opportunity. We could investigate this painting’s authenticity—a genuine case study—and share the whole process with our public as it unfolded, whatever the results. And so it began—a year-long adventure headed to an unknown destination.

Launching the investigation

Each step of the investigative process was documented to form the core of the exhibit Fakes! (illustration 2). In the introductory text panel, I posed the following question: “Is Warriors’ Return an original Remington? Or is it a fake?” I did not know the answer to that question, but I knew I could not solve this mystery by myself. For help, I relied on the expertise of many colleagues, especially Don Murchison, the painting conservator at Glenbow Museum; the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) in Ottawa; and the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West].

Any investigation into the authenticity of a work of art includes both a rigorous scientific analysis and a more intuitive and comparative study, involving a close reading of the painting. Are there elements in the work which are consistent with Remington’s style and his usual subjects? Are there discrepancies? What does the painting depict?

Some clues

In Warriors’ Return, we see a compact group of Blackfeet riding at a measured pace in a bleak winter landscape, led by an older, grim-faced male on horseback. He stares ahead as he advances resolutely toward us. A blanket wrapped around his upper torso leaves his bare right hand free to grasp the reins. A decorated gun case straddles his lap. The neck of his horse is inclined downward. Behind him, and veering to the left, is another mounted man, whose head is hooded by a blanket that is tightly wrapped around his body. To the right and set farther back, is one more warrior. Although his horse moves forward, he turns his head to the left, revealing his profile. He wears the distinctive Blackfeet wolf fur hat and fringed jacket and pants. A rifle, pointing diagonally upwards, rests between his hands. Between him and the central figure, the head of a fourth man can be seen. Much lower down, this man appears to be on foot.

The title of the work, Warriors’ Return, tells us these are warriors returning to their camp with a prisoner in tow. There are other Remington paintings with similar subjects which depict Natives on horseback shown in combination with one or more people on foot. The desolate landscape setting is typical of Remington in three ways: It is generalized with no discernable landmarks; the horizon line is very high; and the vegetation is sparse. In this painting, it appears to be very cold as we can see the breath of the horses and the men in the frosty air. Manes, tails, hair, and snow are blowing in a brisk wind which comes from the left of the image. The horses’ legs are partly submerged in deep snow.

There are footprints visible in the snow in the foreground, suggesting there is another group ahead. Remington included many winter scenes in his work, but was this one authentic?

On closer inspection

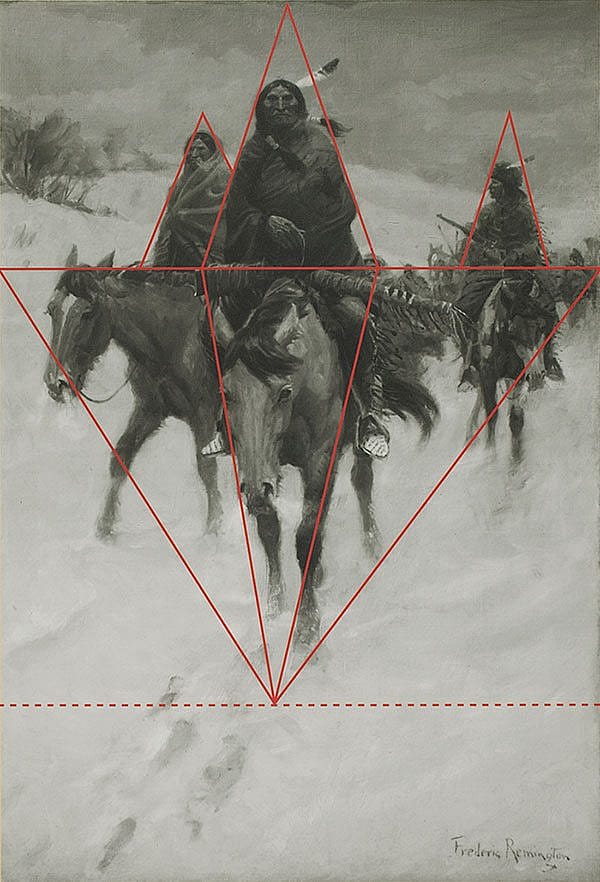

Next was a question as to whether the composition of Warriors’ Return was typical of Remington’s style. Yes and no. As in many of Remington’s other scenes, the figures are placed higher up in the picture; the lowest quarter (the immediate foreground) is left relatively bare. But Remington tended to use a vertical format for single figures and here there are many figures. The most powerful compositional device used in Warriors’ Return is the triangle (illustration 3), which can also be found in many other works by Remington. The triangle is most notable in the dominant male in the center. The apex of the triangle is the warrior’s head, his arms its sloping sides, and its base the long, horizontal gun case. Within the picture there are other overlapping triangles. In Warriors’ Return, the sketchy figures in the background are abruptly cut off by the frame. This type of cropping can also be seen in other works, but it is not a device often found in Remington’s oeuvre or body of work.

The people depicted here appear to be Blackfeet, who represented “real Indians” for Remington. They are similar in type and appearance to Natives in other Remington works. For example, the face of the central man conforms to Remington’s stereotypical representation of the Blackfeet as a “racial” type. Note the low forehead, the pronounced nose, the deep-set eyes, the high cheekbones, and the broad cast of the face.

In his grand studio (recreated at the Center of the West’s Whitney Western Art Museum), Remington proudly displayed his enormous collection of Native material which he used as props in his paintings. It is well known that Remington could be quite arbitrary in the way he used Native clothing, accoutrements, and artifacts. Warriors’ Return features some details which are authentic and some which appear to be invented, such as the horse within the circle motif that is on the blanket of the central figure.

Horses play a central role in Remington’s work, and he knew their anatomy well. But in the Glenbow painting, the musculature of the horses does not seem to be expertly rendered. This could be an indication the work is not by Remington’s hand. A reason for suspicion? Yes, but not conclusive.

Science in the act

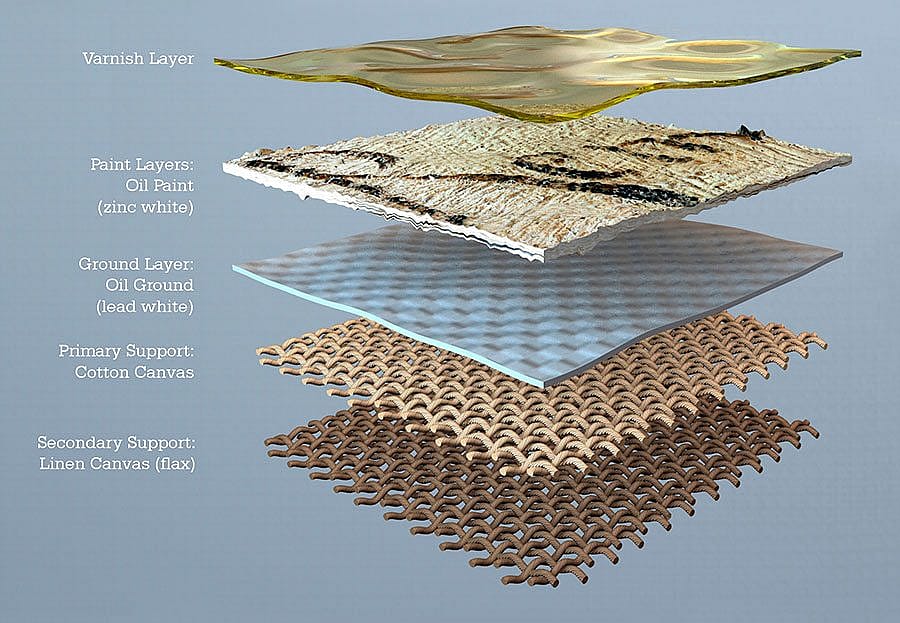

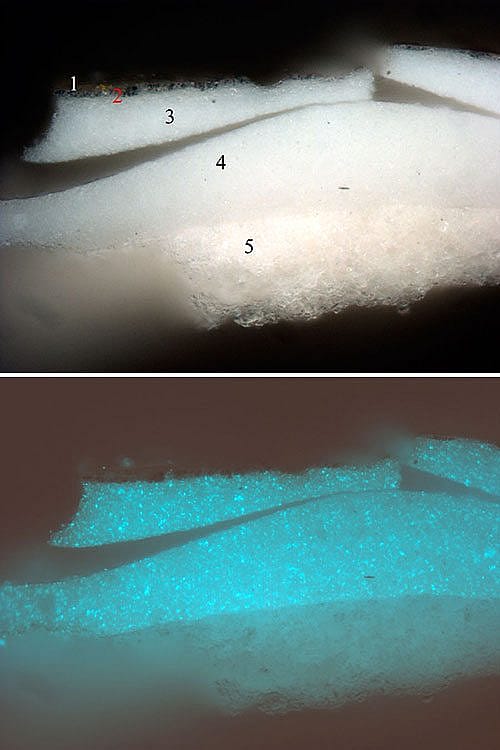

More specific results would come from the scientific analysis, conducted by Glenbow conservator Don Murchison (illustration 4). He proceeded systematically through the many layers of the painting from the bottom to the top. Through microscopic examination and under different lights, he examined and photographed, in turn, the lining, support (canvas), ground, paint layers, and varnish (illustration 5).

Don noted a few anomalies—the painting had been lined even though there was no evidence of damage that would have warranted lining. There was overpainting near the signature area, and the support was cotton, not linen which would have been much more consistent with Remington’s practice. Don knew certain pigments were not in use during Remington’s lifetime. For example, paints made with titanium were introduced to artists in 1928. As Remington died in 1909, the presence of titanium would be undeniable proof that the painting was a fake. Using a technique called XRF (x-ray fluorescence) and a spectrometer (used to measure the wavelengths of light), it was possible to detect the chemical composition in the ground and paint layers. However, no titanium was detected in the original paint and more specialized tests were needed.

Many of these tests required very sophisticated equipment which were not available at the Glenbow Museum. So, Don removed three samples of paint, each about the size of a grain of sand, from three different areas of the painting, including the signature. He sent the miniscule samples to Ottawa to be studied by the CCI. The scientists there employed many specialized techniques to examine the paint layers in cross-section (illustration 6). They were able to identify elements and particles present in each layer of the paint. In addition, they compared the paint used for the signature to the paint in the other parts of the picture. One key finding was the paint for the signature had a different chemical composition than the paint in other areas of the painting!

This was certainly very suspicious but not irrefutable as evidence. In the final analysis, everything we had uncovered pointed to a painting which was genuinely old and which shared many stylistic characteristics with Remington’s work. It had some questionable elements to be sure, but we had not found incontrovertible proof of its “inauthenticity.” Was Warriors’ Return a fake or not? The answer continued to elude us.

Warriors’ travels to the U.S.

There was one more step we had to take in order to find out for sure. Each year, a panel of Remington scholars convenes to study Remingtons at the Center of the West; Warriors’ Return had a date with destiny. We packed our painting and sent it, along with all our documentation, to the Center. Finally, after three months, we received the official report dated April 28, 2004, which was displayed in the exhibit:

“In the opinion of the Committee, this Item is not an original work by Frederic Remington. Although the subject and certain elements of the composition are in keeping with Remington’s thematic choices and stylistic habits, the final technical execution is not consistent with his working methods. The brushwork is not characteristic of his work…the draftsmanship is too cursorily suggested…. Modeling of the horse and human figures…is inconsistent with Remington’s expertise in anatomy…. The signature…does not appear to be by Remington’s hand….”

An unexpected twist

So, not a Remington after all. But who painted this work? The committee did not know, suggesting only that further research be undertaken to try to determine the authorship of the painting. Our exhibit was well underway: texts written, photographs scanned, prints produced, plaques mounted, and the display designed. It was all set and we were almost ready for opening day. Then, at the proverbial eleventh hour, literally days from the exhibition opening, we received a call from Julie Tachick, [then] curatorial assistant in the Center’s Whitney Western Art Museum, who had seen our painting when it was in Cody.

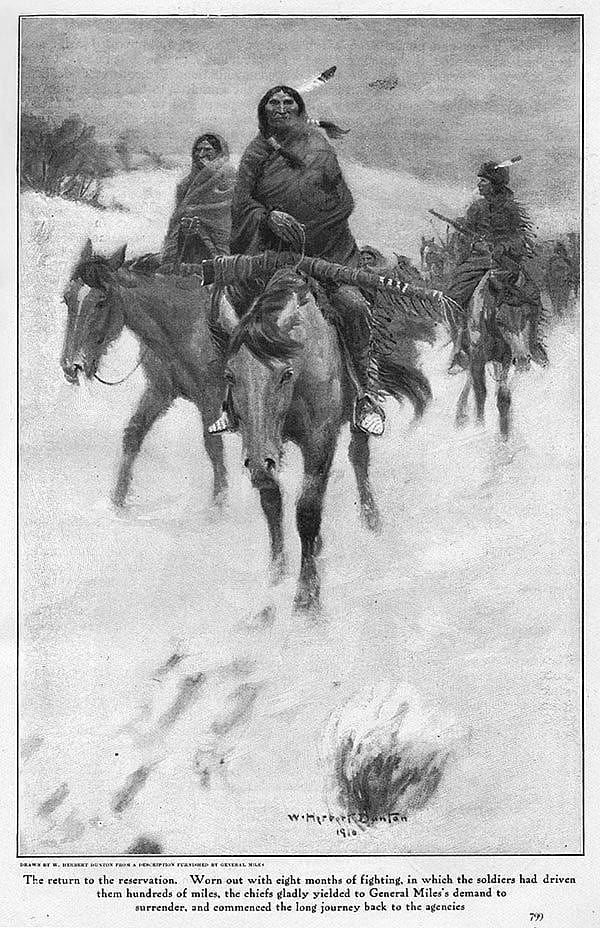

While researching the caper in the Center’s library, and acquiring microfilm from other sources, she’d discovered an image of Warriors’ in a full page illustration in a May 1911 issue of Cosmopolitan Magazine (illustration 7). The image was by artist William Herbert Dunton (1878 – 1936), a well-known illustrator in the American West. It appeared in a article by General Nelson A. Miles, “My First Fights on the Plains.” We were so excited!

Case solved

Without a doubt, this amazing discovery was a must for the show and the following conclusion of our detective story was placed on an added panel:

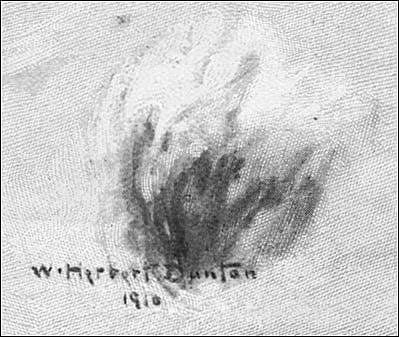

“Finally, we knew the name of the artist! So is this painting a fake? The answer is no. This painting is a forgery, not a fake. In the case of a fake the artist intends to deceive—he would set out to create a ‘fake Remington.’ Clearly Dunton carried out his illustration commission in good faith. He signed and dated his painting and published it under his own name in a national publication. In this case, the fraud could have been committed up to 20 years after Dunton completed his 1910 painting. Recognizing the painting’s striking similarity to works by Remington, the forger went to work. The lower edge of the painting was cut to remove the date. The bush and the signature were scratched out and painted over. The forged signature was added, the varnish applied, and the painting was sold as a Remington. A classic case of forgery.”

Now, the only question is: Who did the forgery and when? To date, no one knows…maybe the case isn’t solved after all.

About the author

Monique Westra is the Senior Art Curator at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. All photos courtesy of the Glenbow Museum.

Post 073

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.