Hickok and His Guns: How Good Were They? – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2003

Hickok and His Guns: How Good Were They?

By Warren Newman, Former Cody Firearms Museum Curator

He came to be known as the “Prince of Pistoleers.” His name was James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. He was born on a farm in Illinois in 1837, but he seemed destined from the outset to be a lawman rather than a farmer. As a young boy, he practiced shooting with a pistol until he became highly proficient in its use. He subsequently left home to seek out a means of livelihood that would capitalize on his skills with a gun. In the process he became the first really famous gunfighter of the American West.

Hickok is reputed to have shot down five desperadoes in Leavenworth, Kansas, when he was twenty-one years of age. In 1861, he is said to have killed a man named David McCanles in Rock Creek, Nebraska. He attracted much attention when he killed another gunfighter in Springfield, Missouri, in July 1865. His opponent was an acquaintance named Davis Tutt. Tutt and Hickok became involved in a dispute over a purported gambling debt. The argument was apparently exacerbated by their amorous interests in the same woman. The end result was that they engaged in a classic walk-down shootout. Although they fired at each other virtually in the same instant. Tutt missed and Hickok’s bullet found its mark, striking Tutt in the chest. Hickok was arrested and tried in a court of law for the shooting, but the jury quickly decided that he had acted in self-defense.

Wild Bill’s growing reputation as a gunfighter earned him the sheriff’s job in Hays County, Kansas. He performed so admirably in the position that he was soon appointed marshal of the bustling cow town of Abilene in the same state. There his personal dominance and marksmanship skills began to assume legendary proportions.

One writer, Colonel George Ward Nichols, claims to have observed Hickok put six bullets into a six-inch letter “O” on a sign between 50 and 60 yards away without using the sights of his pistol. General George Armstrong Custer, for whom Hickok had ridden as a scout, said of him in 1872, “Of his courage there could be no question,” and “his skill in the use of the rifle and pistol was unerring,” but “he was entirely free from all bluster and bravado.” Custer went on to assert, with respect to Hickok as a lawman, that “his word was law.”

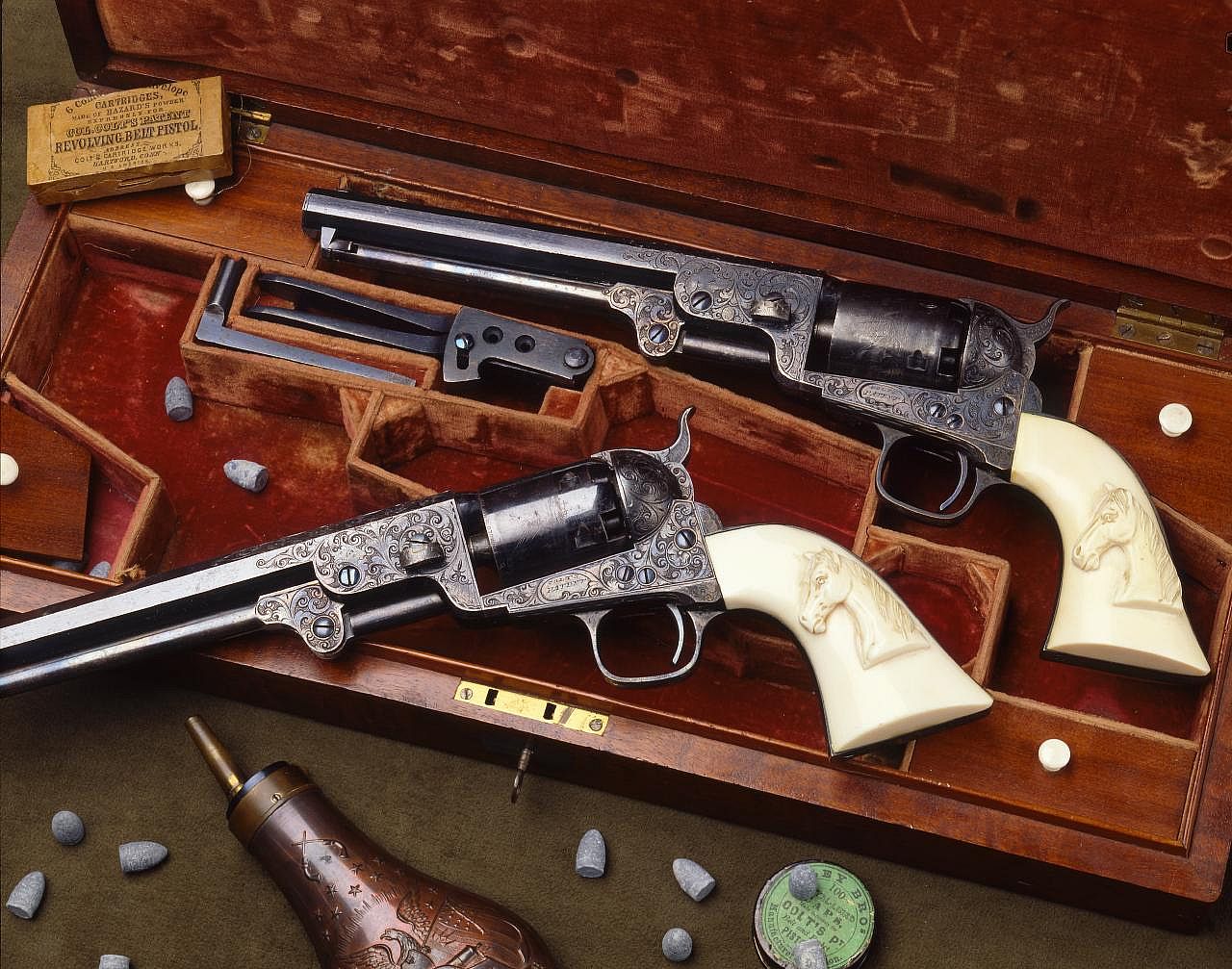

Even after Wild Bill had been murdered, shot from behind while he was playing cards in Deadwood, South Dakota in 1876—a crime for which Jack McCall was tried, convicted, and hanged the following year—the legend continued to grow. Three years later an article in the Cheyenne, Wyoming, Daily Leader described his capabilities with his famous Colt Model 1851 Navy cap-and-ball revolvers:

His ivory handled revolvers…were made expressly for him and were finished in a manner unequalled by any ever before manufactured in this or any other country. It is said that a bullet from them never missed its mark. Remarkable stories are told of the dead shootist’s skills with these guns. He could keep two fruit cans rolling, one in front and one behind him, with bullets fired from these firearms. This is only a sample story of the hundreds which are related to his incredible dexterity with these revolvers.

The journalist’s use of such phrases as “bullets that never missed their mark,” terms like “incredible dexterity,” and the description of a pair of revolvers that were said to be “unequalled by any ever before manufactured in this or any other country” did more than ensure an impressive reputation. They made of him a legend, whose exploits, regardless of their degree of authenticity, were firmly embedded in the minds of the tens of thousands of people who heard and read of him. Wild Bill was, after all, a very opportune man to lionize. He was tall and broad shouldered, with penetrating eyes that seemed to search out the innermost being of others. His long hair, flowing like a mane and accented by his preference for ruffled and fancy clothing and broad-brimmed hats, made him an imposing figure. He was a gentleman, with a deep fondness for the ladies, treating them with personal attention and flawless courtesy.

His mystique had grown in spite of some difficulties along the way during his lifetime. In a gun battle in which he killed Phil Coe over a sign that he considered offensive in Coe’s famous Bull’s Head Saloon, Hickok, sensing further danger, whirled and shot his own deputy Mike Williams who was standing behind him. Even that tragic mistake seemed unable to diminish the magnitude of the legend that enveloped him. “Wild Bill” Hickok became a powerful and enduring image of a professional lawman and deadly gunfighter in the American West. He and others of his kind, like Wyatt Earp, Bill Tilghman, Bat Masterson, several Texas Rangers, and the Colts they carried, were significant agents of change from disorder and uncontrolled violence to a modicum of order and respect for the law in a tumultuous era.

How good were they? Were they men of fairly ordinary capabilities whose exploits were exaggerated in the telling and retelling across the years by people who needed heroes? Were they made into larger-than-life legends by imaginative journalists, by the intentional sensationalism of dime novelists, and later by western movies and television productions? These are questions that need to be asked by thoughtful people who are interested in the story of the American frontier, particularly since the appetite for stirring portrayals of spectacular skills of violence often seems greater than the longing for realism.

Perhaps a good way to find some of the answers is to look more analytically at the saga of Wild Bill Hickok and some of the claims of his shooting skills that have been cited. Fortunately, it is possible to do so against the vastly enlarged database of well over a hundred years additional experience of guns and their capabilities, of the ballistics of ammunition, and of the mental and physiological propensities of men engaged in violent confrontations.

Colonel Nichols’s account of Hickok’s ability to place six bullets into such a small space at 50 to 60 yards without using the sights on his gun cannot be claimed to be completely impossible, but it can be said to be highly unlikely. Even the top shooters speak convincingly of the extreme importance of a clear and steady sight picture with a handgun at such a distance. Further light is shed on the matter by Hickok’s regular practices. He often put on public exhibitions of his shooting skills—probably both to enhance his reputation and to discourage those who might attempt to gain notoriety by trying to gun him down. He would also often engage in friendly marksmanship matches with others who were recognized as outstanding shots. A number of observers attested that in neither instance would he ever shoot without taking dead aim; he was just very quick in acquiring it. It is quite possible that this unusual speed in acquiring a good sight picture might have led observers to conclude that he was not using his sights at all.

The most successful gunfighters across the years have always been men of iron nerve who were smooth and quick in drawing and pointing their guns, but who invariably took sufficiently deliberate aim, except at very short range, to ensure accurate shot placement.

Interestingly, Wild Bill was sometimes beaten in the shooting matches with his skilled friends. The winners, however, would affirm consistently that he was essentially unbeatable in an actual gunfight because of his calmness and poise. Almost everyone in the midst of the crisis of a violent and potentially deadly confrontation experiences a rush of adrenalin that causes a restriction of sight known as “tunnel vision,” shaking hands, unanticipated general body movements and quick, shallow breathing. Hickok had the ability to remain steady, deliberate, and unshaken, enabling him to handle his pistol quickly while using his sights well enough to attain precise shot placement. Another key to his deadliness in a shootout was that he never had the slightest indecision or hesitation in pulling the trigger on an adversary. The reluctance to use deadly force on another human being often results in a momentary delay that costs a combatant his life. Hickok’s ability to control that impulse, along with his speed and accuracy, made him an extremely dangerous gunfighter and contributed to his reputation as a legendary lawman.

What about the Colt Model 1851 Navy percussion revolvers that he favored? How good were they? many contemporary marksmen deride the depictions of both the shooters and the guns of the frontier era. They contend that the skills of the gunslingers were shamelessly exaggerated for effect, and that the guns themselves could not have performed anywhere near the levels claimed. The production of firearms, they say, was not nearly so advanced, nor individual firearms sufficiently well-designed or well-made to have enabled such feats. In addition, the ammunition of the time was too primitive to have been even marginally effective. Given our frequent conviction of the overall superiority of “modern” production machinery and methods, their contentions can be rather persuasive.

Fortunately in this area of interest we are not dependent upon personal opinion alone. There is a limited but solid body of observational and experimental data regarding the speed and accuracy of the guns of the frontier. Some of it is from that era; the rest has been developed more recently by using the guns of that period. An example from the era is provided by a prominent shooting exhibition put on by Texas lawyer, killer, and shootist John Wesley Hardin at the opening of his saloon in El Paso on 4 July 1895.

Hardin pierced cards from a faro deck using a .38 caliber Colt Lightning Double-Action revolver. He shot at close range but quite rapidly. His shot placement was remarkable, often with five shots grouped in the same ragged hole. The double-action guns afforded some advantages for fast shooting and were used by a number of shooters before the turn of the century.

Tests conducted by the U.S. Army with handguns in 1876 and 1898 provided surprising indications of their accuracy. The .45 caliber Colt Single Action Army revolver turned in average groups of 3.11 inches at 50 yards, and in the later trials a Colt Peacemaker shot groups of 5.3 inches at 50 yards and 8.3 inches at 100 yards. These period observations and tests made it readily apparent that frontier handguns were both precisely made and capable of real accuracy.

Contemporary tests of the guns of the West also tend to confirm their effectiveness. In a recent controlled experiment a Colt Model 1851, like the ones used by Wild Bill Hickok, proved capable of putting three bullets in a 3-inch group at 25 yards. A Colt Model 1873 Single Action Army, like the ones worn by Doc Holliday, Jesse James, and Billy the Kid, placed three rounds in a 3 1/2 inch group. A Colt Model 1860 Army percussion revolver shot a three-round 5-inch group. These results are very impressive, particularly in view of the age of the guns.

How good were they? They were astonishingly good—both the best of the men and the best of the guns. They compare favorably with contemporary production guns and lend considerable credence to the claims of the speed and accuracy of the early American gunfighters. Our cynicism about some of those claims is completely understandable, but sometimes they deserve a closer look.

Post 074

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.