Artists in America’s First National Park – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2005

Artists in America’s First National Park

By Peter H. Hassrick, with introduction by Marguerite House

Yellowstone draws artists

Even before its official designation as America’s first national park in 1872, artists have chronicled Yellowstone’s peculiar combination of the magnificent, the terrifying, and the sublime. And today, visitors are still stunned by the height of a geyser and swear they’ve never ever seen that particular shade of aquamarine tinting a steamy thermal pool. They inch toward a railing, the only barrier separating them from the 1,500 foot deep expanse of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone below. They teeter quite literally on the edge, feeling at once exhilarated yet petrified. But once they view the calming, gentle sashay of swans on the Madison River, that queasiness all but disappears. More often than not, travelers return home with scores of photographs that serve a singular purpose: to prove those geysers and pools and waterfalls really do exist. They’ll insist their friends simply must make a visit, saying, “You won’t believe it until you see it.”

And that is, by and large, the role of those others who were drawn to Yellowstone. They were artists in America’s first national park, and they wanted the observer to believe.

Indeed, Thomas Moran, one of the first painters to explore the Yellowstone region, wrote in his later years the following tribute:

I have wandered over a good part of the Territories and have seen much of the varied scenery of the Far West, but that of the Yellowstone retains its hold upon my imagination with a vividness of yesterday…The impression then made upon me by the stupendous & remarkable manifestation of nature’s forces will remain with me as long as memory lasts.

The exhibition Drawn to Yellowstone: Artists in America’s First National Park, which appeared at the Center in 2005, gathered together those impressions, captured in two and three dimensions from Yellowstone’s earliest explorers to the present day. Moran’s works are included, as well as Albert Bierstadt, J.H. Twachtman, Frank Tenney Johnson, and others. Organized by the Museum of the American West, Autry National Center in Los Angeles, California, the assemblage is curated by noted scholar Peter H. Hassrick, who specializes in the art of the American West.

In the excerpt that follows from the autumn 2004 edition of Antiques & Fine Art, and from his book, Drawn to Yellowstone: Artists in America’s First National Park, Hassrick reflected on the Park and those who painted and sketched it:

Yellowstone National Park was not the first of America’s natural marvels to serve as studio and subject for artists in this country. Virginia’s Natural Bridge, the Catskills along the Hudson, Niagara Falls, and once-remote Yosemite Valley were among a host of other locations of the national landscape that were commanding attention from painters by the mid-1800s. Yet in the long history of America’s search for ways to express its national identity and find artistic inspiration in its places of natural wonder, Yellowstone has played a particularly beneficial role.

This far corner of what was until 1890 known as Wyoming Territory, with its remarkable geological eccentricities, has become more than just a symbol of wildness. It has made wild and natural scenery a public experience. Representing the bounty of America, Yellowstone was a mecca for many artists, from whom flowed, like the waters pulsing from its geysers, an artistic energy that at once captivated the public and contributed to its philosophical and aesthetic history.

Determined to be unsuitable for mining or farming, Yellowstone was established as a national park in 1872. Congress stated it was setting Yellowstone aside as a public pleasuring ground, but they were also resolutely determined to preserve the Park’s natural curiosities and prevent private acquisition. Many viewed the creation of Yellowstone National Park as something of a national imperative. Americans were searching for cultural parity with Europe, and America’s scenery was one way the country might favorably be compared. Many also wanted to find symbols of national identity and unity in the aftermath of the Civil War. Moran’s work and that of Albert Bierstadt, such as his Yellowstone Falls, served as those kinds of emblems.

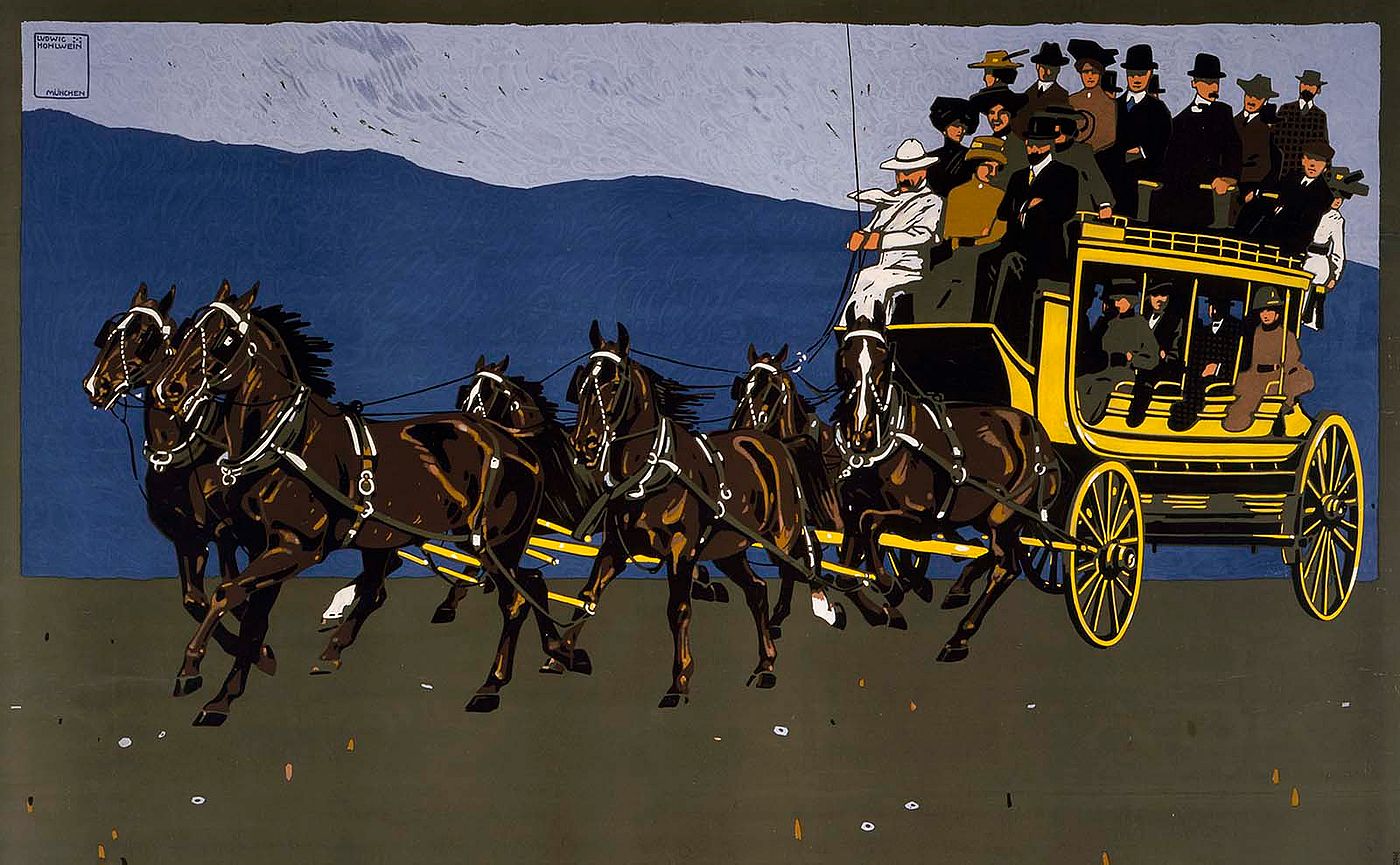

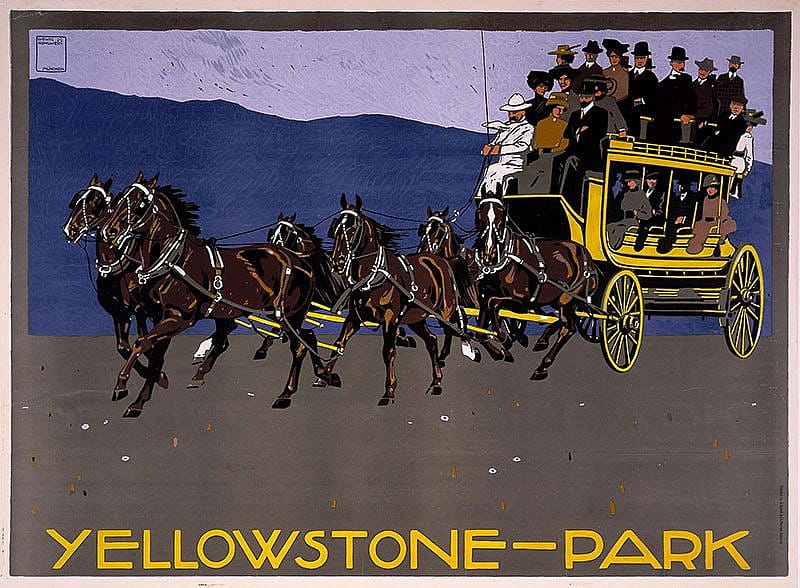

Artists drawn to Yellowstone have displayed a broad range of talent and aesthetic vision. Some, like Abbey Hill who painted for the Northern Pacific Railroad in the first decade of the 1900s, seems to have been attracted by the sheer beauty of the landscape. American Impressionist John Twachtman, who visited Yellowstone in 1895, said he was “so overwhelmed with things to do that a year would not be a short stay…This scenery too is fine enough to shock any mind.” Gustave Krollman came to the Park in the 1920s to paint the geysers, and a fellow German-born artist, Ludwig Hohlwein, who visited Yellowstone around 1910, produced works that promoted the tourism bonanza that Yellowstone experienced then and still enjoys today.

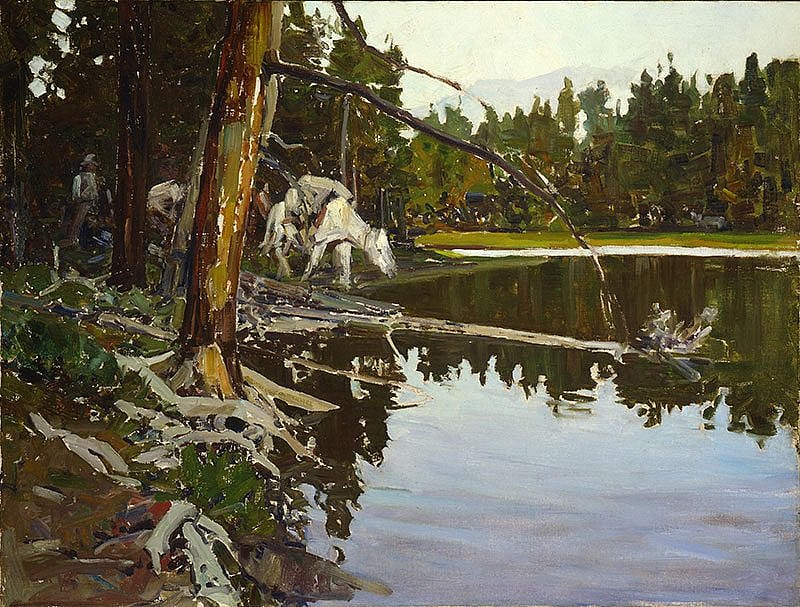

Another who was drawn to Yellowstone was Frank Tenney Johnson. An artist and illustrator by trade, and an adventurer at heart, he found himself at his cousin’s cabin on the Shoshone River just outside Yellowstone’s East Gate in the 1930s. There, Johnson built a cabin and studio, and passed his summer months hiking, packing and painting in and around the Park. When he was lucky, even the composition was provided by nature, as evidenced in his Cove in Yellowstone Park. Design was critical to the success of his pictures, however, no matter how natural the setting.

Still others drawn to Yellowstone found its national park designation a defining moment in American conservation history. The famed environmental writer and activist Enos Mills claimed in 1915 “the establishment of Yellowstone National Park was a great incident in the scenic history of America—and in that of the world. For the first time, a scenic wonderland was dedicated ‘a public park…for the benefit and enjoyment of all the people.'” It represented victory in a long and hard fought battle between the utilitarians and aesthetic conservationists.

Why were artists drawn to Yellowstone? A member of the 1870 Washburn party who explored Yellowstone, N.P. Langford, probably said it best as he observed, “A grander scene than the lower cataract of the Yellowstone was never witnessed by mortal eyes.”

Post 074

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.