Exploring a New Frontier: The Role of Natural History Museums in the 21st Century – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 1999

Exploring a New Frontier: The Role of Natural History Museums in the 21st Century

Charles R. Preston, PhD

Willis McDonald IV Senior Curator of the Draper Natural History Museum

Ed. note: This article is from a series describing the role of natural history museums and plans for the Center’s own natural history museum leading up to its opening in 2002.

In May of 1997, when I first learned that the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] was seriously exploring the possibility of expanding its programming and facilities to include a natural history museum, I had just returned from a working vacation in the Greater Yellowstone region. I was accompanied on that trip by one of the curators on my staff in the Department of Zoology, Denver Museum of Natural History, and one of our new, summer interns. Coincidentally, our “campfire” discussions had drifted around to the challenges faced by today’s natural history museums and the need for a new paradigm in natural history programming. We wondered aloud about how a world-class natural history museum established at the beginning of the new millennium might compare with the museums established a century or more ago. We had no idea that trustees, staff, and consultants at the Center were deliberating the same topic.

Public interest in natural history has soared in recent decades. Bird watching has become the nation’s second most popular recreational pastime (behind gardening), nature programming is among the most popular offerings on television, environmental issues figure prominently in our national dialogue, and our national parks are overwhelmed by visitors. The opportunity for natural history museums to broaden their audiences and fulfill their roles as centers for research and informal public education has never been greater. But established museums face some new challenges that come with changing audiences and technology. To meet these challenges, natural history museums must be as dynamic as the phenomena they address and the audiences they serve. Perhaps ironically, these venerable institutions, so critical in documenting a world of change, are slow to change themselves. Most world-class natural history museums in operation today were established more than a century ago to explore and study the natural world and display its wonders to regional, generally sedentary, audiences. These museums essentially brought the world to their communities, through spectacular dioramas, depicting pristine nature frozen in time behind a glass wall.

Today’s museum visitors, however, are very different from those at the turn of the last century. Audiences today access and process information differently, and are much more mobile, willing, and able to visit Earth’s natural wonders firsthand. They are increasingly sophisticated and interested in learning more from a natural history exhibit than the name and provenance of a specimen or object; they want to know what role it plays in the environment and how it might relate to their lives. They also tend to enjoy actively participating in their learning/recreational experiences, seeking to combine interactive with contemplative opportunities during their museum visit. Museums must strive to understand our audiences and the issues of current and critical interest to them, and we must find new ways of engaging them. But it is essential to avoid any semblance of an amusement park atmosphere, and to continue to provide opportunities within exhibit spaces for quiet contemplation. Thus, the inclusion of interactivity and new technology is crucial, but must not be overused.

Natural history museums are beginning to broaden the focus and voice of program interpretation. Increasingly, the focus of exhibitions is on ideas and current topics, rather than on collections. Collections and other material are used to tell a story instead of being the story. Rarely do current exhibits or other programs reflect the narrow viewpoint of one curator. Instead, most programming is the result of collaboration among curatorial and educational staff within the museum, together with external consultants and even audiences themselves (included in formative evaluations of program ideas). This kind of collaboration is critical if natural history programming is to effectively engage audiences and provide accurate, relevant, and balanced information about complex topics of current interest.

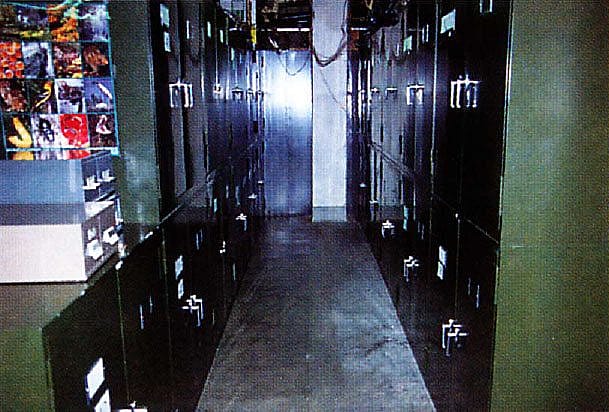

One of the greatest misconceptions about museums is that most collections are on exhibit at any given time. This is especially untrue of most natural history museums. The majority of specimens and other objects stored behind the scenes in natural history museums today are used primarily for reference and research material for scholars. The care of research collections, a traditional hallmark of natural history museums, offers significant challenges for the future. Existing natural history museums have amassed huge collections of specimens and artifacts that serve document the record of life earth and the geologic features and processes at its foundation. The financial commitment needed to properly house and process growing natural history collections is enormous, and sources for significant funding are scarce. Natural history “acquisitions” of the future may, therefore, represent a profound departure from the vast specimen collections amassed during the last two centuries. Though very limited, highly focused collections of specimens and artifacts well be acquired, the bulk of natural history acquisitions may consist of other, more easily stored, maintained, and accessed material documenting the natural history of a focus region. The emphasis of these acquisitions will be on use (for both public exhibition and scholarly pursuits), rather than storage. This material may include extensive sound and visual recordings, and electronic databases documenting human land use and distribution of flora, fauna, geological features and climate.

To remain as popular and relevant as the subject matter they present, natural history museums must continue to learn and grow with their audiences and exploit current technology. The overarching role of natural history museums in the 21st century will be to continue to explore and develop new knowledge about the natural world, attract and engage diverse audiences, and provide them with accurate, pertinent, and balanced information needed to make informed decisions about the stewardship of natural resources. To fulfill this role, we must understand our audiences, what attracts them to museums, and how they access information. We must continue to find new and effective ways of engaging audiences and employ participatory experiences where appropriate and feasible. Our programming should reflect collaborative rather than compartmentalized efforts. We must be fiscally responsible, and seek innovative, perhaps even more effective, means of exploring and documenting the continuing story of life on earth without incurring the enormous expenses of ever-increasing collections storage facilities. Perhaps most important of all, the natural history museums of the 21st century must recognize that human-kind does not exist beyond the realm of nature, and nowhere on each does nature exist beyond the influence of humankind. Our exhibits and programs should thus incorporate humans as a part of nature rather than apart from nature.

The Buffalo Bill Center of the West is surrounded by one of the most compelling biological and geological theaters in the world. The environment of the West binds all of the components currently featured at the Center. As our trustees, staff, and partners continue to contemplate the appropriate expression of natural history programming here, we will build on the traditions of existing world-class museums, including our own, and forge a crystalline vision of a natural history museum for the 21st century.

Post 079

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.