Buffalo Bill’s fight against Wyoming’s outlaws, part 2 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2008

“We want them dead rather than alive” — Buffalo Bill’s fight against Wyoming’s outlaws, Part 2

By Jeremy Johnston

William J Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum; Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western History; and Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s autobiography published in 1879 contained many “true” accounts of him chasing and capturing various desperados in the Wyoming region. “All along the stage route were robbers and man-killers far more vicious than the Indians,” wrote Buffalo Bill. In part two of “Outlaws,” Buffalo Bill relates several stories about Wyoming outlaws, the first encounter of which occurred during his employment with Russell, Majors, and Waddell, when he claimed he worked as a Pony Express rider.

Joseph Slade

In 1861, fifteen-year-old Cody found himself working at the Horseshoe Station, located some thirty miles west of Fort Laramie, where he was “occasionally riding pony express and taking care of stock.” A violent gunfighter, Joseph Slade, managed the Horseshoe Station and acted as Buffalo Bill’s boss. Slade’s violent exploits on both sides of the law were well known throughout the West and eventually led to his lynching by an angry group of Montana vigilantes. As a station manager for the Pony Express, Slade killed a number of horse thieves. After killing one such victim, Slade sliced his ears off, dried out the gruesome remains, and carried the trophies in his pocket to honor the event.

Famed writer Mark Twain described a tense encounter in Wyoming with Slade in his travelogue, Roughing It. While sitting at the same table with Slade, Twain noticed the coffee pot contained only one cup of coffee yet both their mugs were empty. When Slade offered Twain the last cup of coffee, he quickly refused to take it. Twain said, “although I wanted it, I politely declined. I was afraid he had not killed anybody that morning, and might be needing diversion.” Slade ignored Twain’s refusal and filled the author’s cup with coffee. Twain declared, “I thanked him and drank it, but it gave me no comfort, for I could not feel sure that he would not be sorry, presently, that he had given it away, and proceed to kill me to distract his thoughts from the loss.”

Unlike Twain, Buffalo Bill did not fear Slade. Instead, he stated in his autobiography that “Slade, although rough at times and always a dangerous character—having killed many a man—was always kind to me. During the two years that I worked for him…he never spoke an angry word to me.”

Hunting bears, eluding outlaws

Buffalo Bill recalled an adventure on a solo bear hunt near Laramie Peak during this time at Horseshoe Station. “Very early in my career as a frontiersman, I had an encounter with a party of these [outlaws] from which I was extremely fortunate to escape with my life,” wrote Buffalo Bill in his autobiography. He did not kill any bears during this hunt: Instead he found himself trapped in a den of horse thieves hoping to escape with his life.

After killing two sage hens for his evening dinner, Buffalo Bill prepared a campsite for the night only to notice a herd of horses grazing near a dugout in the distance. Hoping to find shelter for the night, he walked up to the dwelling and boldly knocked on the door. When the door opened, he found himself face-to-face with “eight as rough and villainous men as I ever saw in my life.” The outlaws recently killed a ranchman and ran off with his horses, and Buffalo Bill observed it “was a hard crowd, and I concluded that the sooner I could get away from them the better it would be for me.” The suspicious outlaws questioned Cody about his presence in the area, if there were others accompanying him, and how he discovered their hideout.

Buffalo Bill barely escaped his would-be captors by using a clever ruse: he claimed the need to tend to his horse, which he left back at his campsite. Two outlaws accompanied Buffalo Bill back to his campsite to get his horse and sage hens. While the three men trekked back to the dugout, Buffalo Bill intentionally dropped one of the sage hens and asked the closest outlaw to pick it up. When the villain bent down to retrieve the bird, Buffalo Bill hit the outlaw over the head with his pistol and then shot and killed the other horse thief. Quickly mounting his horse, Buffalo Bill rode off into the darkness.

After hearing the shot, the remaining outlaws rode after the young adventurer. Buffalo Bill eluded the outlaws, now dangerously close, by abandoning his horse and then setting off on foot back to Horseshoe Station, twenty-five miles away. After returning safely, Buffalo Bill and Slade rode back to the dugout to capture the rest of the horse thieves. There they found only an empty dwelling and a fresh grave with the body of the outlaw killed by Buffalo Bill. Cody later boasted that his “adventure at least resulted in clearing the country of horse thieves. Once the gang had gone, no more depredations occurred for a long time.”

The notorious Bill Bevins

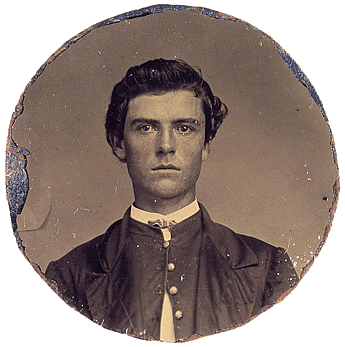

According to Buffalo Bill’s autobiography, the most infamous Wyoming bandit he encountered was Bill Bevins. Before the aggrandizement of other legendary outlaws like the Wild Bunch, Bill Bevins was one of the most notorious bandits in Wyoming, making him the perfect foil to Buffalo Bill as a lawman.

As Buffalo Bill told it, Bevins and another outlaw named Williams stole some horses and mules in 1869 from Fort Lyon on the eastern plains of Colorado. General Carr ordered Buffalo Bill, Bill Green, and others to retrieve the stolen livestock and bring the criminals to justice. The posse tracked the desperados to Denver where they arrested Williams, who was trying to sell the government mules at a horse auction with the government horses’ brands altered from “US” to “DB.” When the posse threatened Williams with lynching, he told the scouts the location of his camp where they would find Bevins. Buffalo Bill and his companions quietly surrounded the camp, then quickly surprised and captured Bevins.

Escorting the captured horse thieves back to Fort Lyon proved to be even more challenging for Cody and his fellow posse members. After traveling seventeen miles east of Denver, in the direction of Fort Lyon, the party camped on Cherry Creek for the night. To prevent Bevins and Williams from escaping, the outlaws’ shoes were removed in camp. While Buffalo Bill and his companions slept, Williams kicked a guard into the campfire to give himself and Bevins a chance to escape. Bevins grabbed his shoes and ran off into the darkness. Buffalo Bill, awakened by the noise, managed to confuse Williams, preventing his escape.

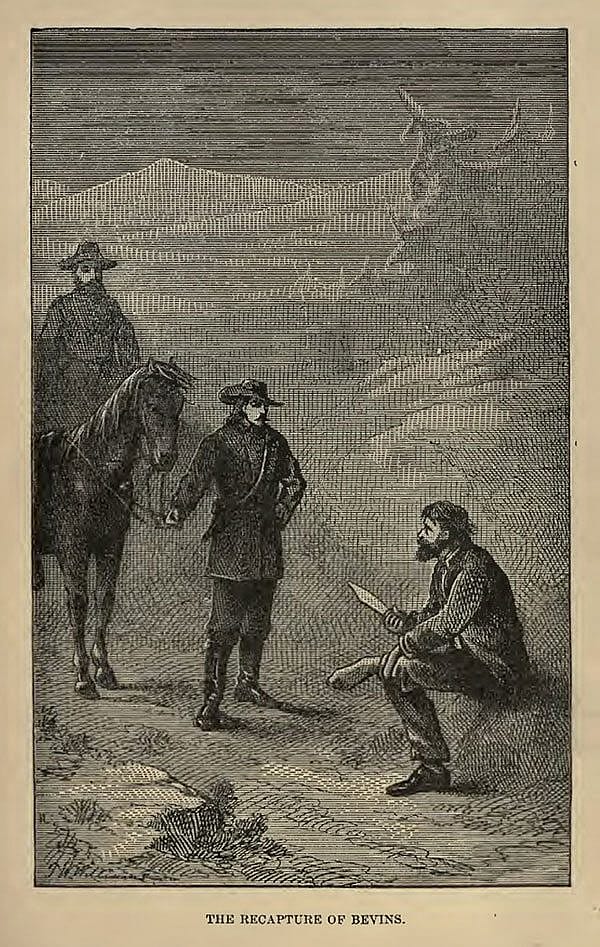

Green chased after Bevins, firing his pistol at the fleeing outlaw which caused Bevins to drop one of his shoes. Buffalo Bill and Green then mounted their horses and set out to find Bevins, who, despite having only one shoe, managed to cover a great distance through the plains covered with snow and infested with prickly pear cactus. Buffalo Bill later recalled that nearly every one of Bevins’ tracks was spotted with blood.

Cody also said, “Bevin’s run was the most remarkable feat of the kind ever known, either of a white man, or an Indian. A man who could run barefoot in the snow eighteen miles through a prickly pear patch was certainly a ‘tough one,’ and that is the kind of person Bill Bevins was…. I considered him as ‘game’ a man as I have ever met.”

Once in range, “I told him to halt or I would shoot,” recalled Buffalo Bill. “He knew I was a good shot and coolly sat down to wait for us.” After being caught, the outlaw requested Buffalo Bill’s knife and proceeded to dig out the cactus quills from the bottom of his bare foot. Buffalo Bill and Green switched off riding one horse and offered the other to Bevins, who reportedly never complained about his poor condition the whole way back to camp.

After joining the rest of the posse with the recaptured Bevins, they continued on their way to Fort Lyon. On the Arkansas River, the posse and their prisoners camped in a vacant cabin. Due to Bevins’ poor condition, the guards relaxed their vigilance, and Williams managed to escape into the night, never to be seen again.

When he reached Fort Lyons with Bevins, Buffalo Bill escorted the prisoner to Bogg’s Ranch on Picket Wire Creek and turned him over to the civil authorities. But Bevins quickly escaped—not to Buffalo Bill’s surprise—and continued to plague the area with his crimes. Buffalo Bill wrote in his autobiography that “I heard no more of [Bevins] until 1872, when I learned that he was skirmishing around on Laramie Plains [southeast Wyoming] at his old tricks. He sent word…that if he ever met me again he would kill me on sight.”

Bevins reappears

Cody summed up the later career of Bevins this way, “He finally was arrested and convicted for robbery and was confined in the prison at Laramie City [present day Laramie, Wyoming]. Again he made his escape, and soon afterward, he organized a desperate gang of outlaws…when the stages began to run between Cheyenne and Deadwood [South Dakota]…they robbed the coaches and passengers, frequently making large hauls of plunder…finally most of the gang were caught, tried and convicted, and sent to the penitentiary for a number of years. Bill Bevins and nearly all of his gang are now confined in the Nebraska state prison, to which they were transferred, from Wyoming.”

Prison records and other historical sources verify Buffalo Bill’s account of Bevins’ later criminal career. On August 13, 1876, near Fort Halleck, Wyoming, Bevins and Herman Lessman, a well-known horse thief, attacked Robert Foote, a prominent rancher. Bevins pinned Foote to the ground and choked him until Mrs. Foote began hitting Bevins with a large stick. When Bevins grabbed for Mrs. Foote, her screams alerted a neighbor who rushed to the scene causing Bevins and Lessman to run away. Law officials captured Bevins near Fort Fetterman, Wyoming, and transported him to the Albany County jail in Laramie to await trial.

While waiting for a court appeal, Bevins escaped with three other prisoners aided by “Pawnee Liz,” a local prostitute, who sawed through the bars on the cell window. Bevins soon found his way to the Black Hills where he joined Clark Pelton to form a gang of road agents and robbed three Cheyenne-Deadwood stagecoaches. One robbery resulted in the unfortunate death of Johnny Slaughter, a stagecoach guard.

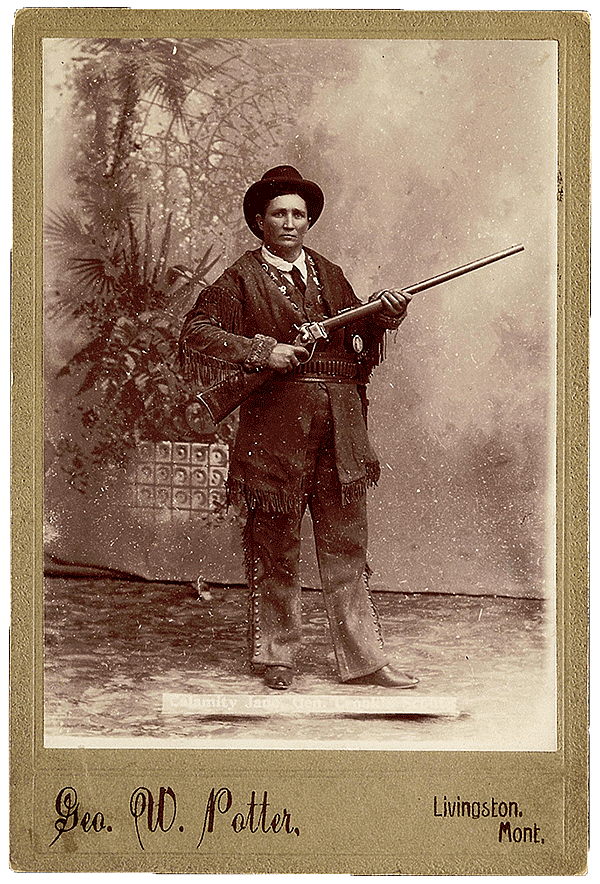

Did Calamity Jane enter the picture?

Bevins later fell on hard-times because of a woman of bad character, who some historians claim was Calamity Jane. It is reported that Bevins and Calamity Jane lived as husband and wife, and she rode with his Black Hills gang.

After they fled from the Black Hills to Wyoming, the woman later identified as Calamity Jane overheard Bevins and the other gang members threatening to kill fellow outlaw Robert McKimie who was then buying supplies at South Pass City. When McKimie returned, Calamity Jane informed him of the band’s murderous intentions.

When he learned of the plot, McKimie and the woman rode off with the gang’s $8,000 in plundered gold dust acquired from the stagecoach robberies. This left Bevins with nothing to show for his crimes except a pocket watch he stole from a passenger. During his search for McKimie and the so-called woman of bad character, Bevins was recaptured in Lander, Wyoming, on July 6, 1877, as he ate his dinner.

Albany County Sheriff Daniel Notage escorted Bevins back to the Albany County jail to be sentenced for the attack on Foote. Bevins attempted to escape again by digging a tunnel under the floor. He followed this escape attempt with a successful getaway only to be trapped again and brought back to stand trial. The judge sentenced Bevins to serve eight years in the Wyoming Territorial Prison at Laramie for attacking Robert Foote; he was never tried for the stagecoach robberies.

On August 6, 1877, William Bevins became inmate number 141 at the Wyoming Territorial Prison. Prison records indicate Bevins was 39 years old and he listed his occupation as a farmer. It was noted that his mother lived in Ohio, and he had an uncle who lived at Hat Creek, Wyoming. On February 9, 1877, Bevins was transferred to the Nebraska State Prison where he remained until his release on March 12, 1883, serving five years and seven months.

Frank Grouard

Surprisingly, Frank Grouard, famed army scout and close acquaintance of Buffalo Bill’s, was a friend of Bevins. In the account of his life written by Joe Debarthe, Grouard

offered a different perspective of the infamous outlaw.

Grouard met Bevins in the 1860s during the Montana Gold Rush, where Bevins was shot and cut eighteen times for “winning” $120,000 at the poker tables. In the Black Hills region, Grouard nearly arrested Bevins a number of times for stealing horses and robbing stagecoaches, but he would always let him go “on account of his being so friendly to me in my boyhood when I met him at Helena years before.”

In 1886, Grouard met Bevins for the last time, and the former outlaw didn’t have a penny to his name. Grouard reported that Bevins died in Spearfish, South Dakota, shortly after their last meeting. “Bevins was between 45 and 50 years old at the time of his death,” according to Grouard. “He was an odd man, anyway you could take him. He would do anything for a friend. He was a perfect type of the western hard man of his time.”

Sizing things up

Many historians question the accuracy of Buffalo Bill’s autobiography. Unfortunately, many of the events he narrated cannot be verified by outside historical sources. This includes his accounts of his first Indian kill and his service in the Pony Express. In addition, Cody’s account of Bevins’ capture and his barefoot escape does not appear in the Colorado papers; however, the Colorado Transcript did report that Bill Green was in “this part of the country on duty, accompanying Bill Cody, Gen. Carr’s chief of scouts.”

Cody’s autobiographical account of Bevins’ later life is fairly close in detail to other accounts depicting Bevins as a shady character with the uncanny ability to escape from justice. Did Buffalo Bill select Bevins to be the perfect foil in a fictional account of his capture? As with so many historical “myth versus fact” questions, we simply may never know. Until other historical records are uncovered, the answer will remain unclear.

About the author

Jeremy Johnston is a direct descendant of John B. Goff, a hunting guide for President Theodore Roosevelt. Johnston grew up hearing many a tale about Roosevelt’s life and times. In 2006, Johnston was one of the first recipients of a Cody Institute for Western American Studies research fellowship at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West; “Buffalo Bill and Wyoming outlaws” is a result of that study. Johnston taught Wyoming and western history at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming, for fifteen years. While a graduate student at the University of Wyoming, Johnston wrote his master’s thesis titled Presidential Preservation: Theodore Roosevelt and Yellowstone National Park. He continues to research Roosevelt’s connections to Yellowstone and the West as he writes and speaks about Wyoming and the American West. Johnston has served as Curator of the Center’s Buffalo Bill Museum and is now Historian of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, the Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western History, and Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody.

Post 082

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.