Buffalo Bill’s fight against Wyoming’s outlaws, part 1 – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2008

“We want them dead rather than alive” — Buffalo Bill’s fight against Wyoming’s outlaws, Part 1

By Jeremy Johnston

Former Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum; now Historian, Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western History, and Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody

For any historian, separating fact from fiction in the wild tales of the Old West can be a daunting task. Never is this truer than with the life and times of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. A tale can be twisted, turned, and tossed around a dozen ways in a performance by the Great Showman himself or written about in his musings. Factor in comparing the historical record with Buffalo Bill’s autobiography and other materials, and it’s easy to see just how difficult a task this can be.

On the afternoon of November 1, 1904, two unidentified men rode into the town of Cody, Wyoming. They dismounted and strolled into the First National Bank, pulled out pistols, and ordered the cashier to throw up his hands. Witnessing the robbery in progress from his office inside the bank, cashier I.O. Middaugh ran to the street yelling for assistance. One of the robbers ran after Middaugh, grabbed him, and fired two fatal shots into his neck and chest.

Hearing gunfire, the other bank robber fled the bank and untied the horses, and both men rode quickly out of town—without any money—wildly firing their guns. Many Cody residents fired their weapons at the fleeing bandits. A newspaper reporter, George Nelson, mounted his horse and bravely rode after the bandits alone. He was later joined by John Thompson, Frank Meyers, Carl Hammitt, and a Deputy Sheriff Chapman. The posse caught up to the two bank robbers and fired on them until one of the outlaws killed a posse member’s horse. The posse halted, and the bandits continued to flee into the night.

Shortly after the failed robbery, the national press reported sensational accounts about the hold-up and noted that William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody would soon ride to the rescue. The New York Times proclaimed in their headline “Buffalo Bill in Pursuit.” Other newspapers’ headlines noted “‘Buffalo Bill’ Soon to Reach Trapped Outlaws, “‘Buffalo Bill’ on Trail of Bandits,” and the New York Journal reported “Cody Bandits at Bay: ‘No Quarter,’ [says] Buffalo Bill’s Command.”

All across America, the news depicted in great detail the adventure of Buffalo Bill chasing down vicious Wyoming desperados. Clearly the public assumed Buffalo Bill would save the day by capturing these two violent outlaws who callously took the life of an innocent bank teller.

At Omaha, Nebraska, Buffalo Bill gave reporters the following statement: “I have wired my manager at Cody, Col. Frank Powell, the old Indian fighter and scout, to offer a large reward for the capture alive of each robber…and I told him to double the reward if the outlaws were killed. We want them dead rather than alive.”

When asked if he would join the posse, Cody replied, “Will we join the hunt? You bet we will…within ten minutes after our train arrives there we shall be in the saddle with our guns, and away we go. These Englishmen [Cody’s guests at the time] will get a real touch of Western life such as they never dreamed of…. We don’t intend to let those fellows get away if we have to follow them all Winter.” Cody also introduced Chief Iron Tail who sat at his side armed with two pistols, “And here is my old Indian scout…and he is dead anxious to get into the scrimmage.”

Buffalo Bill was then asked who the robbers were and why they targeted his Wyoming town, to which he replied, “I am not surprised at the hold-up, for it was well known that the Government had hundreds of thousands of dollars on deposit in that bank. The Government is building a five-million-dollar irrigating system in the Big Horn, and the funds are deposited in Cody. That’s what tempted the robbers in this case. They undoubtedly came over from the Hole-in-the-Wall country and are trying to get back into that den of thieves, but we will head them off, and of course a stiff fight will take place when we catch them.”

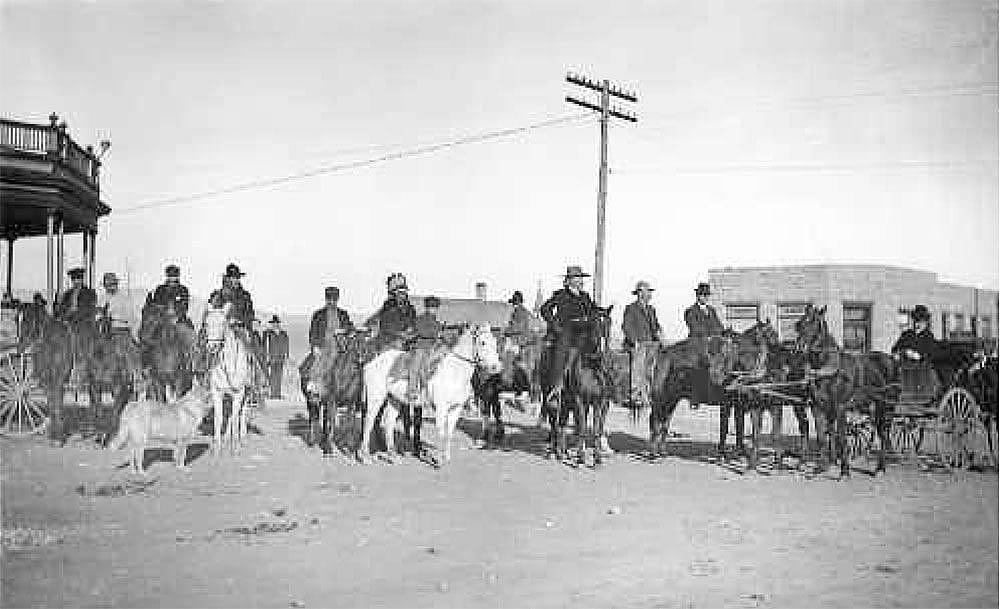

The New York Times followed up with another report proclaiming that Buffalo Bill, accompanied by his English guests and Iron Tail, had reached Cody, Wyoming, where they were joined by thirty local cowboys. Buffalo Bill and his posse started on their all-night, hundred-mile ride to join the Cody citizens who trapped the two outlaws near Kirby, Wyoming.

The Times also reported that Harvey Logan—alias Kid Curry, a notorious member of the Wild Bunch—had joined the gang “and may give the posses some hard fighting.” Never mind that Logan committed suicide rather than surrender during a shootout on June 9, 1904, well before the Cody Bank Robbery!

The paper claimed that Buffalo Bill and his posse would cover the distance to Kirby, Wyoming, in fourteen to sixteen hours. Undoubtedly, the press assumed it would only be a matter of time before Buffalo Bill caught up with these ferocious Wyoming bandits to punish them for their crimes. After all, Buffalo Bill captured countless numbers of bad guys in dime novel stories and in his Wild West shows. It seemed the legend would now become fact.

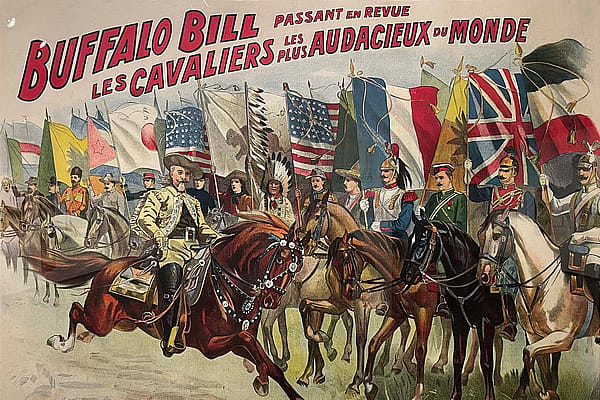

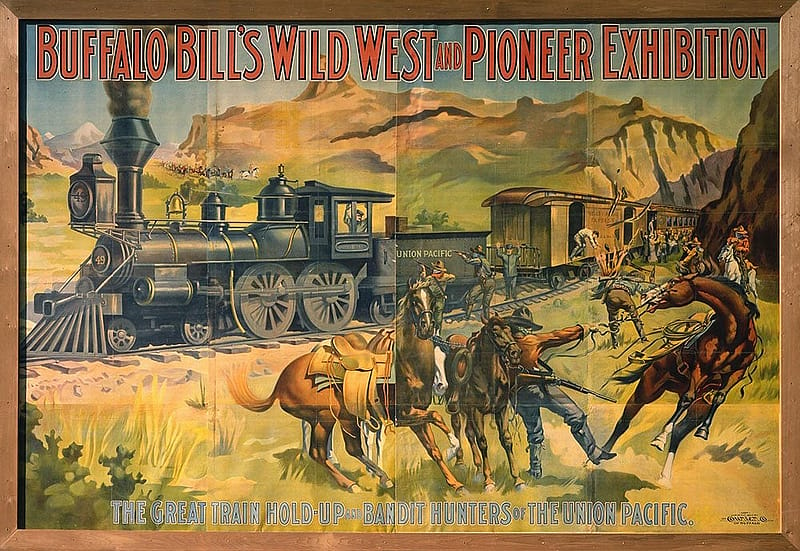

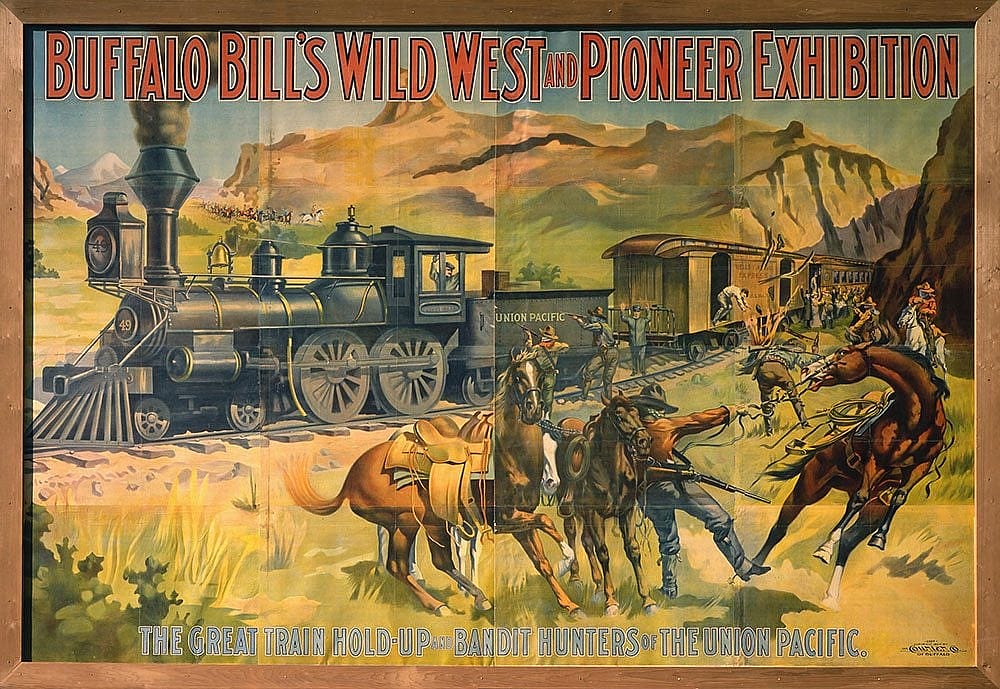

Clearly, Buffalo Bill’s own public persona as a lawman evolved in those popular dime novels. In these stories, Buffalo Bill grew from a scraggly bearded frontiersman in buckskins to a sharp dressed detective sporting a well-groomed goatee. His role as a lawman later found its way into his Wild West show where villains attacked the Deadwood Stage or express trains only to meet their deserved fate when Buffalo Bill arrived to save the day.

Events like these were graphically depicted by colorful posters furthering the image of Buffalo Bill as a great lawman. One such poster was too graphic for citizens of Paterson, New Jersey. According to the New York Times, officials censured the poster for the Great Train Robbery due to its violent depiction of outlaws armed with guns and knives.

In his own writings, Buffalo Bill also heaped praise on other famous western lawmen, noting he was close friends with many such individuals, especially Wild Bill Hickok. “‘Wild Bill’ I had known since 1857,” wrote Buffalo Bill. “He and I shared the pleasure of walking a thousand miles to the Missouri River.” Buffalo Bill praised Hickok’s skill with a pistol and included a number of exciting narratives about Hickok’s fights in his autobiography.

Nevertheless, shortly after the attempted robbery of the First National Bank in Cody, bad news began to appear in the national press. The New York World reported the bank robbers evaded the posse and reached the Hole-in-the-Wall country in Johnson County, Wyoming, in the north-central part of the state. Sheriff Fenton of neighboring Bighorn County and his men planned to sneak into the outlaws’ lair in disguise to bring them to justice.

While the national newspapers reported on the Cody robbery and the intense manhunt for the robbers, the Cody Enterprise reported far less exciting details of the incident and criticized the coverage provided by their eastern counterparts. “Some of the write-ups of the horrible occurrence in Cody…are of the burlesque order and treat the deplorable happening as a subject for the exhibition of a large amount of humor,” reported the Cody Enterprise. “This flippant style, doubtless prepared solely for eastern consumption, where the citizens’ literary and news diet consists principally of dare-devil doings and murderous happenings ‘in the West,’ conveys doubtless an impression that our people are of the semi-barbarous stamp…”

The Enterprise quickly dispelled the notion that millions of dollars were deposited in the Cody bank, “It will be many years probably before the bank contains any such enormous sums of money as mentioned.”

As for Buffalo Bill riding into Cody, bringing the bandits to justice and restoring law and order to the Bighorn Basin, the residents of Cody, Wyoming, had no such expectations of their heroic town-founder. Townspeople were more worried about Buffalo Bill not being properly welcomed back to the Bighorn Basin because of the failed bank hold-up. The Cody Enterprise reported the robbery ruined a planned reception for Buffalo Bill and “acted as a damper upon the festivities planned… However, it is nevertheless true that our people are pleased to again welcome one who has acquired such great fame at home and in foreign lands…”

Indeed, the truth of the matter of the days following the robbery was far from eastern newspaper accounts. The fact was, as the local paper would report, that Buffalo Bill and his guests checked into the Irma Hotel the evening of November 3, 1904, only two days after the robbery. Accompanying him were an English officer, Captain W.R. Corfield; Mr. and Mrs. E.F. Stanley of London; Mr. Henry Lusk, a German scholar; Mike Russell of Deadwood and close friend of Buffalo Bill; Russell’s son James; William Sweeney, the conductor of the Wild West Band; Mr. H. Brooks and Judge M. Camplin from Sheridan, Wyoming; and Mr. H.S. Ridgely of Cody. Chief Iron Tail, who figured so prominently in early press reports of the supposed posse, was not mentioned in the guest list. Buffalo Bill and his party never did join the posse. Instead, after they rested a few days in Cody, Buffalo Bill escorted his guests to his famed TE Ranch southwest of Cody for a hunting excursion—a far cry from an expedition to capture robbers.

As Cody’s residents returned to their daily routines, the Cody Enterprise joked, “Bandits on Tuesday, railroad president and other big corporation officials on Sunday. It’s getting so in Cody that a fellow can’t tell whether to wear his six-shooter or his full dress coat upon going out.”

As Buffalo Bill hunted with guests near his ranch, the two bandits who attempted to rob the bank in Cody successfully escaped. Luckily for these two would-be bank robbers, the legend did not become fact. Instead, two ferocious desperados escaped the legendary lawman Buffalo Bill, much to the disappointment of his admiring spectators.

Buffalo Bill’s 1879 autobiography contained many so-called “true” accounts of him chasing and capturing various desperados in the Wyoming region. “All along the stage route were robbers and man-killers far more vicious than the Indians,” wrote Buffalo Bill. His first encounter with Wyoming outlaws occurred during his employment with Russell, Majors, and Waddell, when Cody claimed he worked as a Pony Express rider. In the next issue of Points West, read more about Buffalo Bill and his run-ins with Wyoming outlaws.

About the author

Jeremy Johnston is a direct descendant of John B. Goff, a hunting guide for President Theodore Roosevelt. Johnston grew up hearing many a tale about Roosevelt’s life and times. In 2006, Johnston was one of the first recipients of a Cody Institute for Western American Studies research fellowship at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West; “Buffalo Bill and Wyoming outlaws” is a result of that study. Johnston taught Wyoming and western history at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming, for fifteen years. While a graduate student at the University of Wyoming, Johnston wrote his master’s thesis titled Presidential Preservation: Theodore Roosevelt and Yellowstone National Park. He continues to research Roosevelt’s connections to Yellowstone and the West as he writes and speaks about Wyoming and the American West. Johnston has served as Curator of the Center’s Buffalo Bill Museum and is now Historian of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, the Hal and Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western History, and Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody.

Post 081

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.