The Buffalo People – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 1995

The Buffalo People

By Emma I. Hansen

Curator Emerita of the Plains Indian Museum

Religion is such an integral part of the daily lives of Plains Indian peoples that it cannot be separated from other important activities. Among the buffalo hunters of the Plains, ceremonial cycles were so intertwined with the yearly round of economic activities that one could not proceed without the other. Plains Indian people considered the buffalo a gift from the Creator; they understood that they had to take care to ensure the continued abundance of the herds and successful hunts. Buffalo hunts were undertaken in cooperation with religious leaders, who performed ceremonies before the hunts and prayers at proper times during them.

Although other animals were hunted by Plains tribes, the buffalo, being the largest, was the game of greatest economic importance. The abundant meat from a buffalo could be prepared fresh or cut into strips and dried for later use. From the buffalo also came the raw materials from which the necessities of life—tipi covers, shields, bone and horn tools, hide robes and clothing, and hide containers—were manufactured. Women worked long hours cleaning, scraping, softening and preparing hides for the family’s use or for trade.

Buffalo often figured in early tribal traditions. Men preserved reminiscences of hunts through stories, song, or paintings on robes and tipis. Below the strip of porcupine quillwork on this buffalo robe from the Plains Indian Museum collection, three men wearing capotes are hunting three buffalo. Another man is butchering the kill. The quillwork strip covers the seam where the hide was split along the spine when the animal was butchered.

People of the Plains village tribes such as the Mandan, Pawnee, Wichita, and Hidatsa, who derived part of their living from growing corn and other crops, also depended heavily on buffalo. These bands lived in earth or grass lodge villages along fertile river valleys at least half of the year, but they also seasonally traveled out into the prairie grasslands to hunt buffalo. The ceremonies of these tribes reflected the importance of both farming and buffalo hunting to their economies.

For the Mandan of the Upper Missouri River, approximately half the ceremonies performed in the yearly cycle had to do with raising corn, and the other half related to ensuring the continuance of buffalo herds and successful hunts. During the winter before beginning their hunt, buffalo-calling ceremonies were held to bring the animals closer to their villages.

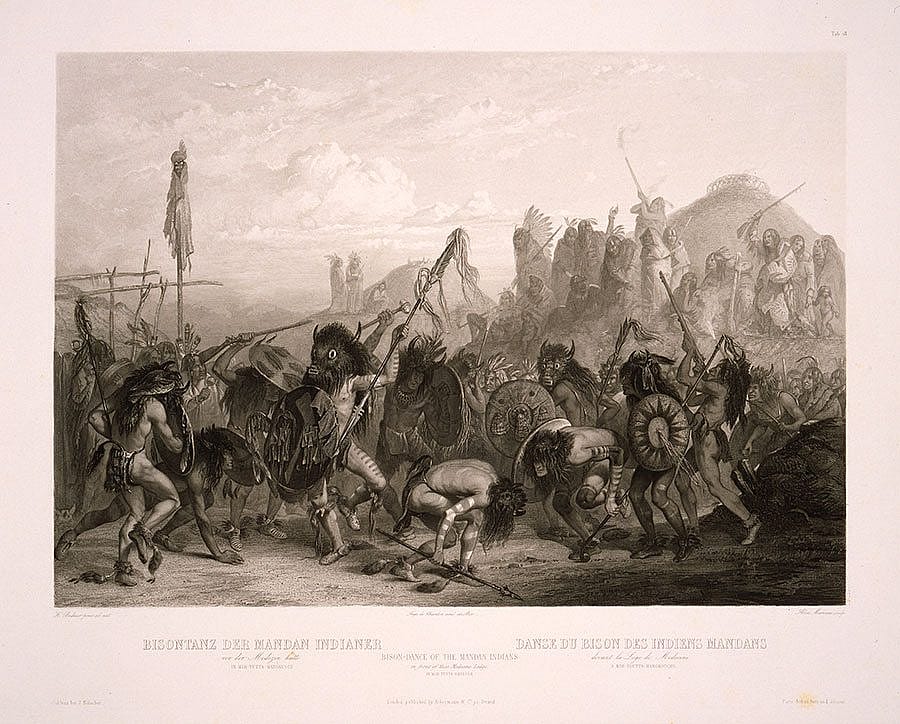

The Okipa ceremony took place during the summer. Although this ceremony included many natural elements, the image and importance of the buffalo were primary features. Both George Catlin, who visited the Mandan in 1832 – 22, and Karl Bodmer, who accompanied Prince Maximilian on an expedition in 1834, recorded the Okipa ceremony. It was held in early summer after the corn and other crops were planted and before the people left on the hunt, and sometimes in late summer after the hunt. The ceremony dramatized the creation of the earth, its plants, animals and people as well as the history of the tribe. The performance took place over four days and included impersonations of buffalo bulls by selected men. For this dramatization the men wore masks of tanned buffalo hide, hide breechcloths and wrist and ankle decorations of buffalo hair, and they carried buffalo hide rattles. An example of a buffalo mask from the Plains Indian Museum collection is pictured.

The Okipa is one of several aspects of the Mandan’s complex ceremonial life that survived the smallpox epidemic of 1837 which almost decimated the tribe. The Okipa continued to be performed intermittently through the 1860s and 1870s, as commercial hide hunters were destroying the vast herds of buffalo. The last performance of the Okipa by the Mandan was recorded in 1889, as the Ghost Dance movement was beginning on the Plains. The conditions of reservation life which prohibited the traditional economic activities of farming and hunting and religious ceremonies brought about many changes for the Mandan and other Plains tribes and forever altered their rich ceremonial life.

For Plains Indian people today the buffalo retains its symbolic importance. Many tribal leaders are working to bring the buffalo back by establishing herds on their reservation lands. There, the buffalo can continue to be a part of the economic as well as spiritual lives of Plains Indian people.

Post 084

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.