Crafted by Nature: An Ecological Profile of the North American Bison – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2000

Crafted by Nature: An Ecological Profile of the North American Bison

By Charles R. Preston, PhD

Willis McDonald IV Senior Curator of Natural Science, Draper Natural History Museum

Through the early evening mist and across the broad valley, we could barely make out eight to ten large, dark forms casually milling about near the forest edge. Upon closer inspection with our spotting scope, we were able to distinguish three smaller, reddish animals virtually surrounded by the larger figures. A cool, light breeze filled the valley, causing us to turn our collars up and tug our wide-brimmed hats down a notch. It was early June 1995, and this was Lamar Valley in the northeastern portion of Yellowstone National Park. My wife, Penny, and I were eavesdropping on a small nursery herd of bison, including the three recently born, cinnamon-colored calves. Suddenly, a large female on the periphery of the herd became alert, raising her head and directing her nose and eyes first one way and then another.

As if choreographed by Baryshnikov, the individual animals deftly merged into one dense mass with some twenty eyes and nostrils surveying the scene. Without warning, the large cow broke formation and began a brisk march toward the woods. The rest followed in single file, with the calves near the center of the column. They slowly disappeared from view, melting into the forest and the mist, and left us to question whether these behemoths were real or only ghosts of our imagination.

Unique Experience

We never saw the wolves or bear that, in all likelihood, inspired the bison behavior that evening. However, we returned to the same area early the next morning to observe six wolves feasting on an overnight elk kill and harassing a pair of coyotes. What we witnessed in 1995 could easily have been witnessed 150, 250, or even 5,000 years ago across much of the lower 48 United States. But, due to the decline and near extinction of the bison, gray wolf, and grizzly in the region,, our experience took on special significance. We found ourselves in one of the few places left in the entire world that contains virtually all the key elements that spawned and honed the animal we herald as a national and western icon: the North American buffalo, or bison (Bison bison).

Forebears

The earliest, direct ancestors of our North American bison arose in southern Asia in the late Pliocene, some four million years ago. These very first bison were relatively small, fleet-footed animals. But, as the global climate and vegetation changed, so too did the bison clan. During the Ice Age, larger more robust bison began to dominate the northern plains of Eurasia. One of these beasts, known to science as Bison priscus, crossed the Bering land bridge from Siberia to Alaska more than 300,000 years ago. Cave paintings of the Upper Paleolithic Era, together with a mummy uncovered in Alaskan permafrost, indicate that this animal possessed long, graceful horns and an ornate fur coat quite different from its modern descendants. Like modern bison, however, Bison priscus was a herd animal, gaining some protection from predators through sheer numbers. This bison ran from predators, but must have also confronted them on occasion in social defense formations, using the outward-pointing tips of its horns as weapons. And these Ice Age predators were formidable foes indeed!

Adapt to Survive

Potential bison predators included powerfully-built saber-toothed cats, scimitar cats, American lions, short-faced bears (larger than any living bear species) and large, roving packs of dire wolves. These predators no doubt helped engineer the replacement of the large B. priscus with the even larger Bison latifrons. Bison latifrons had larger, thicker horns and a much more massive shoulder hump than did B. priscus. It was a superb, high-speed runner. The large body size made it tough for predators to tackle and accommodated large organs for increased gas exchange and blood circulation needed for rapid, sustained flight. Valerius Geist (in Buffalo Nation, Voyageur Press, 1996) suggests that the larger horns sported by B. latifrons were more important as a signal of general vigor and genetic “fitness” to potential mates than they were for fending off predators. Nonetheless, B. latifrons’ defensive strategy, much like B. priscus before it, must have included both flight and confrontation. Bison latifrons was extremely successful on this continent, remaining a characteristic species of western North American fauna for well over 250,000 years. The last B. latifrons populations disappeared about 22,000 years ago. Succeeding B. latifrons as an important herbivore in North America was the slightly smaller-bodied Bison antiquus, which subsequently died out about 10,000 years ago.

Transformation Continues

Today’s Bison bison, rising to prominence in North America only during the last few thousand years, is roughly 30 percent smaller than its massive ancestors. Climate change, bringing cycles of drought and associated food shortages in North American grasslands, encouraged downsizing of the bison. But other factors were also important.

Dale Guthrie (in Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe, University of Chicago Press, 1989) suggests that recent bison morphology and behavior evolved primarily in response to a changing cast of predators. During the Ice Age, bison were confronted with ambush predators, such as the short-faced bear and saber-toothed cats, and large packs of pursuit predators, such as dire and gray wolves. Thus, there was pressure for bison to be able to stand and fight (against sudden ambush) and run fast and far (away from pursuit predators). But, when most of the big ambush predators disappeared by the end of the Ice Age, the primary threat remaining was the gray wolf, a pack-hunting, pursuit predator. Although bison may occasionally confront an attacking grizzly, standing ground to face a large pack of attacking wolves is not generally an adaptive strategy. Consequently, according to Guthrie, small-bodied, small-horned bison, more suited to fleeing than fighting, evolved in the post-Ice Age environment.

Built to Run

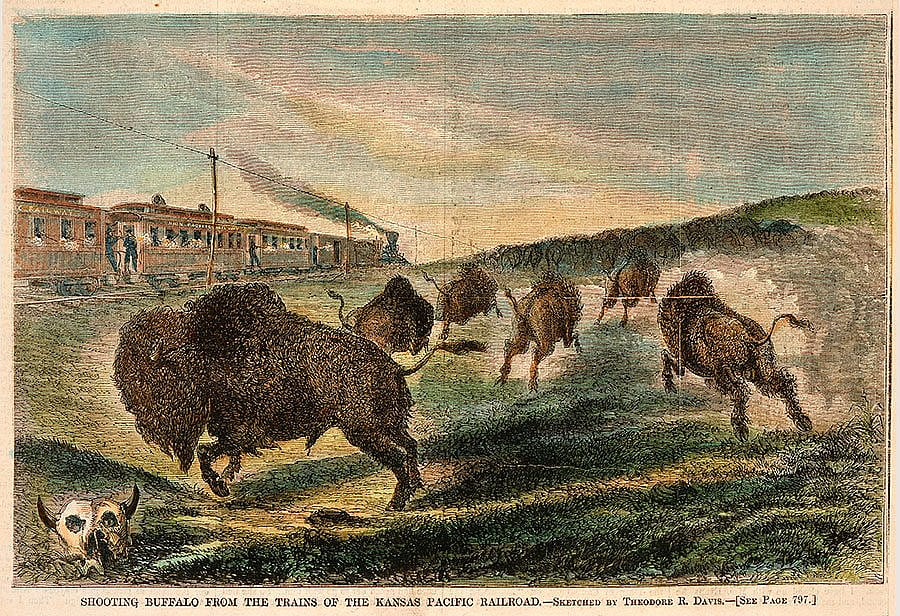

Valerius Geist has extended the argument to suggest that modern bison are able to outdistance wolves through power and endurance, in addition to speed. He points out that, although smaller in size, modern bison are built for power running, up and down varying terrain. They are thus able to take advantage of gullies and hillsides to put distance between themselves and pursuing wolves. Geist further suggests that human predators helped shape the modern bison. Bison that stood their ground to confront Paleo-Indian hunters armed with hand-held spears were quickly eliminated from the population, whereas those individuals that were predisposed to run away from these two-legged predators survived to contribute their genes to future generations. (Two-legged tourists who have approached bison too closely might attest, however, that these modern beasts do not always choose flight over aggression.) Of course, running away did not prove effective in avoiding near extinction at the hands of later predators equipped with weapons that could kill at great distances.

The Shoe Fits

The modern bison is widely regarded as an American icon, but it also serves as a model of the evolutionary process that helps shape living things to fit their environment. Charles J. (Buffalo) Jones, quoted in Colonel Henry Inman’s Buffalo Jones’ Adventures on the Plains ([1899], 1970) gives this colorful account of how well the North American bison is matched to its environment: “Nature is never more persistent in any of its creations that in that of the buffalo’s anatomy, or in its habits so suited to its wild environment. A more perfect animal for the strange surroundings of its habitat could not have been constructed. It is ever prepared for the severest blizzard from the far north, or the hottest sirocco of the Torrid Zone. It is so constructed that it faces every danger, whether it is the pitiless storm from the Arctic regions or its natural enemy, the gray wolf of the desert.”

Jones may have overstated his case just a bit. After all, the present-day ecological systems of western North America are relatively young, and their inhabitants are not as well adapted to this place as they might be after a longer period of environmental stability. Nonetheless, the bison, crafted by nature through eons of change, represents a unique solution to a unique suite of environmental challenges. As with all other species, the future of the bison will continue to be shaped by changes in its environment. Increasingly, those changes will be directed by human choice.

Post 089

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.