Folk Art of the Frontier: McCullough’s Leap – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 1994

Folk Art of the Frontier: McCullough’s Leap

By Robert Engel

Former Research Assistant, Whitney Western Art Museum

Between 1968 and 1981 the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] received from the American folk art collection of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch generous donations of eight nineteenth-century oil paintings, including McCullough’s Leap by an unknown artist. In developing their collection the Garbisches established a strong focus:

We saw in these…works of art those unique qualities of simplicity, forthright directness, and creative vitality in color and design, which set them apart as being indigenous to our country, so genuinely American.

Enthusiasm for folk art has not met with universal acceptance. Folk art does not easily fit into the academic traditions of art history, which investigates styles, periods, regional characteristics and other identifiable influences. Since the emergence of formal academies of fine art during the Italian Renaissance, critical analysis has been largely based on how, an artist’s work compares to prevailing academic precepts. The folk artist, however, is unaware of, and is therefore relatively unaffected by, academic standards. Art critics have thus had difficulty recognizing the folk arts as part of what they are trained to evaluate. Since the 1920s, collectors and critics have been somewhat arduously discovering American folk art. The attention (and more recently the inflation in price) has spurred a broad debate concerning folk art’s identity and artistic value: is it worthy of scholarly attention? Should it hang in serious art museums? Is it “real” art? The Garbisches believed that these paintings “merit an important place not only in the history of American art, but in the history of world art as well.”

All eight paintings, which the Garbisches gave to the Center, are of American frontier subjects, and each contains Native American figures. At least four depict specific historical events between Indians and whites. In four paintings, including McCullough’s Leap, the Indians are depicted as menacing; yet in two others they are romantic figures and noble forest philosophers. In the final two the Indians are consequential bystanders, added to emphasize the wildness and remoteness of the setting. Together, these eight paintings convey a strong sense of how ordinary white Americans perceived their nation’s pioneering experience and the Native Americans whom they were displacing. Six paintings are unsigned and thus far remain unattributed, yet all are clearly painted by different artists.

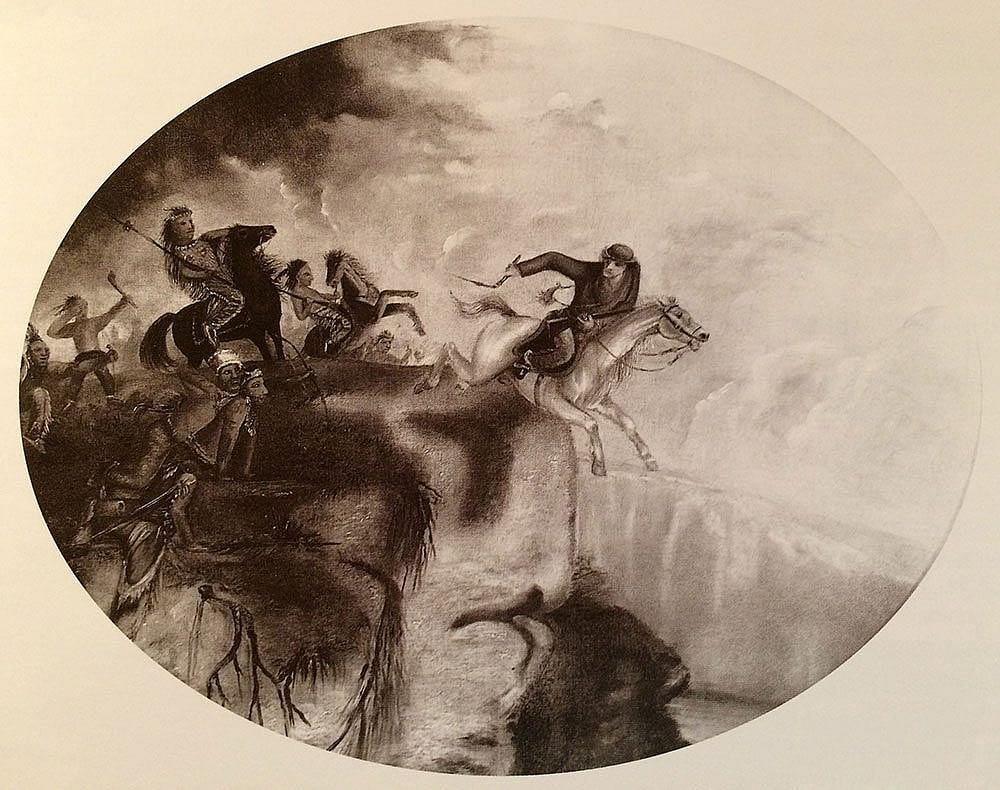

Paintings classified as folk art by their style often reveal some awareness of academic fine art. The anonymous artist of the Center’s painting of McCullough’s Leap, for example, copied an 1852 lithograph which was produced as a collaboration between two well-known European artists, Karl Bodmer (1809–1893) and Jean Francois Millet (1814–1875).

Bodmer’s Art

Swiss-born Bodmer accompanied Prussian Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied on an exploratory expedition to the American West in the years 1832–34. Bodmer made watercolor scenes of American Indian life which are among the greatest accomplishments of early western art. Maximilian wrote an account of the trip titled Travels in the Interior of North America and illustrated it with prints made after Bodmer’s watercolors. Several of these prints are in the Whitney Western Art Museum’s collection.

In 1849, Bodmer moved from Paris to the Fontainebleau forest hamlet of Barbizon, where he met Jean François Millet, at that time a struggling, unknown painter. Later Millet was recognized as one of France’s most important 19th-century artists. He imbued his subjects of solitary French peasants at work, as in The Sower, with religions power and piety.

Soon after moving to Barbizon, Bodmer was commissioned to produce images for a set of lithographs depicting the exploits of American frontier heroes. Bodmer recruited Millet’s help in composing these images. Four lithographs were produced, two depicting the capture and rescue of the daughters of Daniel Boone and James Callaway, one illustrating the torture of Simon Butler, and one portraying the heroics of Samuel McCullough, whose name is spelled “McColloch” in many accounts.

McCullough’s Story

The story of McCullough’s leap is described in numerous nineteenth-century frontier histories and is told, dramatically, from McCullough’s point of view. According to the stories, on September 2, 1777, a large band of Wyandot Indians attacked the small Ohio River town of Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), forcing the townspeople to take refuge in nearby Fort Henry. News of the siege soon reached Short Creek, about 20 miles up river, from which Major Samuel McCullough and 45 volunteers swiftly rode to Wheeling’s rescue. Arriving at the fort and remaining in the rear of his command, McCullough was suddenly cut off from his men and surrounded. The Indians, who wished to torture the infamous white warrior before killing him, held their tomahawks. This gave McCullough a chance to bolt.

The ensuing chase ended atop Wheeling Hill. McCullough was once again surrounded, except for an almost perpendicular precipice 150 feet high with Wheeling Creek at its base. His decision was immediate; rather than succumb to the horrors of torture, he struck his heels against the side of his steed, who sprang forward toward the precipice and they made the fearful leap. The Indians could only stand and admire. They had lost an opportunity to torture their most hated enemy. At least he was now dead. In the next instant, however, their astonishment grew tenfold when, from that impossible height, they watched as the Major climbed the opposite bank of Wheeling Creek and rode safely away.

Bodmer and Millet

In October 1832, Prince Maximilian’s party had traveled from Pittsburgh to Wheeling. It is possible that Bodmer made a sketch of the site of McCullough’s leap at this time, and that he and Millet may have worked from such a sketch in Barbizon 19 years later, though no such sketch is known.

Whatever drawing Bodmer may have contributed to the landscape, art historians agree that stylistically, the figures are all Millet. Years after the lithographs were published, when challenged with the question of attribution, Bodmer himself certified that Millet drew the figures. Unquestionable evidence of Bodmer’s consultation with Millet (who had very little knowledge of Native Americans) can, however, be seen throughout their version of this event, titled Pursued by Indians.

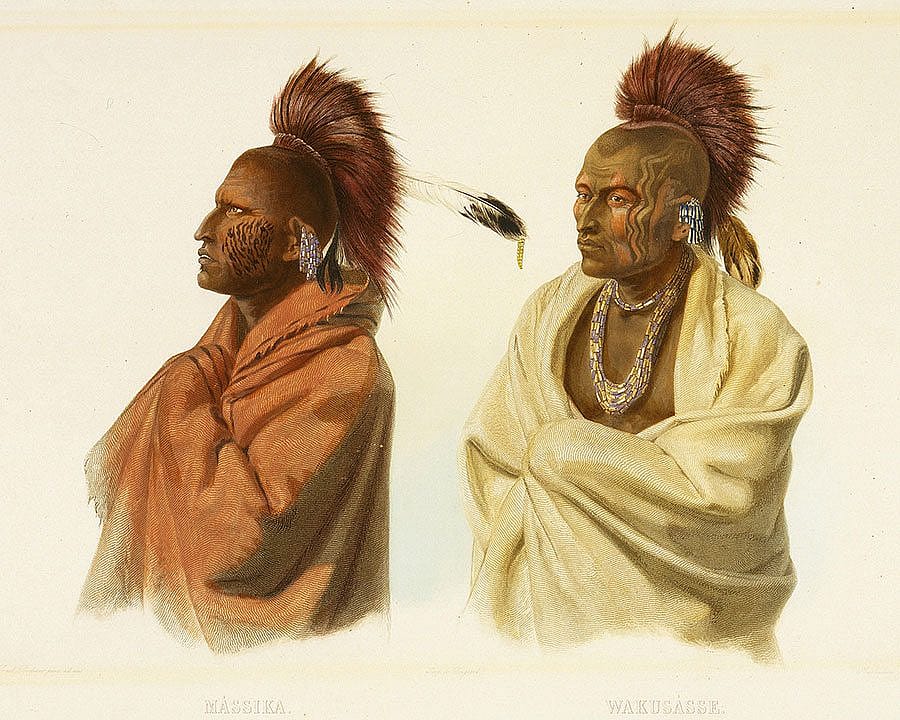

The turban worn by the archer is similar to a rare albino buffalo turban worn by an Hidatsa named Birohka in Bodmer’s print Scalp Dance of the Hidatsa (Minatarres) Indians. The warbonnet with horns and eagle feathers worn by the Indian on the halting horse also appeared in this print. The two most prominent lances in the lithograph have the same characteristics as a Saki and Musquakie lance in Bodmer’s study titled Indian Utensils and Arms. On the rearing horse in the background, the Indian rider wearing a roach headdress is based on a portrait in Bodmer’s image Saki Indian, Musquakic Indian. Bodmer’s influence on Millet is evident in the Indians who fill the cliff in Pursued by Indians, all of whom are 1830s Sauk and Hidatsa rather than 1770s Wyandots. Although Bodmer had sketched eastern Indians on his way out West, by the 1830s their attire was mostly made up of commercial trade goods. Millet apparently preferred to depict a more “wild savage.”

McCullough’s leap is a celebrated tale of early American folklore. To believe such an heroic story of rough-hewn self reliance is to believe that America itself is born from such qualities, and that its future is assured. It was not important to Bodmer and Millet or to their commissioners that the scene be historically accurate; nor was this important to the American purchasers of the lithograph, including the anonymous artist who reproduced it. The French businessman who commissioned Bodmer to make lithographs of heroic American pioneers in action understood the marketability of such subjects.

Folk Art

In comparing the anonymous artist’s painting of McCullough’s Leap to the Bodmer-Millet lithograph, it is easy to see the folk artist’s lack of technical ability. Details are attempted, but they are generalized. Three-dimensional forms such as the edge of the cliff appear flat, despite the artists attempt to describe this edge with overhanging foliage and the horse’s curving shadow. Some proportions are awkward; the climbing Indian’s head, for instance, is much too small. Facial features, which Millet showed as highly expressionistic, are here broadly painted caricatures.

The viewer must decide by what rules folk art should be judged. American modernist painters of the post-World War I era were among the earliest collectors of American folk art. They admired its innocence and freedom from conventional rules. They also recognized in it many precursors to modern academic conceptions of reducing natural objects to minimalist abstract forms.

For historians, American folk paintings can be windows to the past- remarkably honest and accurate reflections of the customs, values, material culture, and the general appearance of our ancestors. But for many, what is most attractive about these paintings is their quaintness, their homeliness.

About the author

Robert Engel worked as art Intern arid Research Assistant in the Whitney Museum between 1989 and 1991.

Research for this essay came from the project for a catalogue of the Whitney’s paintings, funded in part by a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, Inc.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.