Sam Colt and Henry Ford: Industrialists with Vision – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2003

Sam Colt and Henry Ford: Industrialists with Vision

By Maryanne S. Andrus

Former Brown Foundation, Inc. of Houston Curator of Education

Social histories of the American Industrial Revolution have shed light on the management of factories and working conditions for laborers over the past hundred years. Within this sweeping panorama of labor history, there are unique voices that invited—or forced—change; some voices came from men who have become icons of America’s industrial power. Others who contributed valuable expansion and growth to labor conditions, though, have remained relatively unknown. Two manufacturing giants, Samuel Colt and Henry Ford, differ in the level of fame they achieved yet illustrate a similar kind of personal power and determination—shared characteristics that shaped American manufacturing for generations.

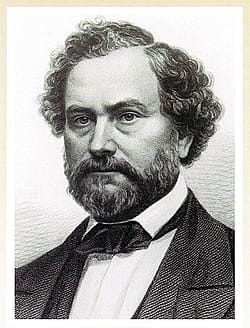

An appreciation of Sam Colt’s contribution to America’s history does not lie solely with his development of superior, repeating firearms. Lesser known is his inventive vision in his Hartford, Connecticut factory: the use of interchangeable machine parts, assembly line production, implementing a shorter, ten-hour workday, addressing employees’ physical discomforts within the factory, providing recreational outlets for employees, and building modern, custom housing for his work force. His personal charisma and the infrequent but harsh use of coercion are also elements that helped shape his factory. Colt’s commitments to his invention and to overseeing successful mass production were fundamental to his success.

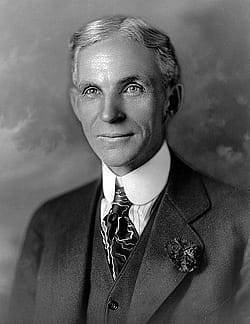

Henry Ford is a world-renowned figure of early twentieth century automobile manufacturing. His fame rests on both his personal drive to manufacture a reliable and affordable automobile and a factory system borrowed from successful management processes of earlier industrial pioneers. A generation later than Colt, Ford adopted the practice of using interchangeable machine parts, assembly line production, and addressing employees’ housing needs. However, he did bring unique vision to the workplace, pulling together all parts of the manufacturing process under one twelve-acre roof at the Rouge Plant in Dearborn, Michigan. To the assembly line process, he added a moving assembly conveyor. As well, Ford implemented the $5 workday in 1914, his version of profit sharing with employees. In a less positive light, however, his leadership was defined by a personality known to be complex and, at times, contradictory. This was coupled with a regrettable reliance on coercive, sometimes brutal, control of employees’ lives.

Similarities between these two manufacturers are striking. Both men were self-made, having only attended a few years of schooling: Sam in an apprenticeship at his father’s silk mill in Hartford and Henry at the one-room Scotch Settlement School in Dearborn. They married distinctive, compelling women who remained faithful to them in life and their “best” memories in death. Both industrialists drew on their own hard beginnings when organizing their factories, implementing new working conditions to motivate factory employees to devoted service. Both men suffered through business failure before they established the factories that built their fortunes. The Patent Arms Manufacturing Co. operated from 1836 – 1842 before it folded. It was reopened in 1848 as the Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Co. Ford made two unsuccessful attempts to build a company before the Ford Motor Company was incorporated in 1903, with Ford as vice-president and chief engineer. In addition to similarities in fortune, it seems undeniable that Ford studied and learned from Sam Colt’s business acumen.

Overarching control of employee’s lives was also a trait shared by the two. Colt was sued in the 1850s for coercing employees’ votes for the Democratic Party and for firing 66 Republican employees. Similarly, Ford adopted many paternalistic policies to “reform” his employees’ personal lives. He was one of the nation’s foremost opponents of labor unions in the 1930s, hiring toughs to break up labor rallies. His strong-arm tactics culminated in the “Battle of the Overpass” in 1937, where one man suffered fatal injuries, many others were seriously injured, and Ford was court-ordered to stop interference with union activity.

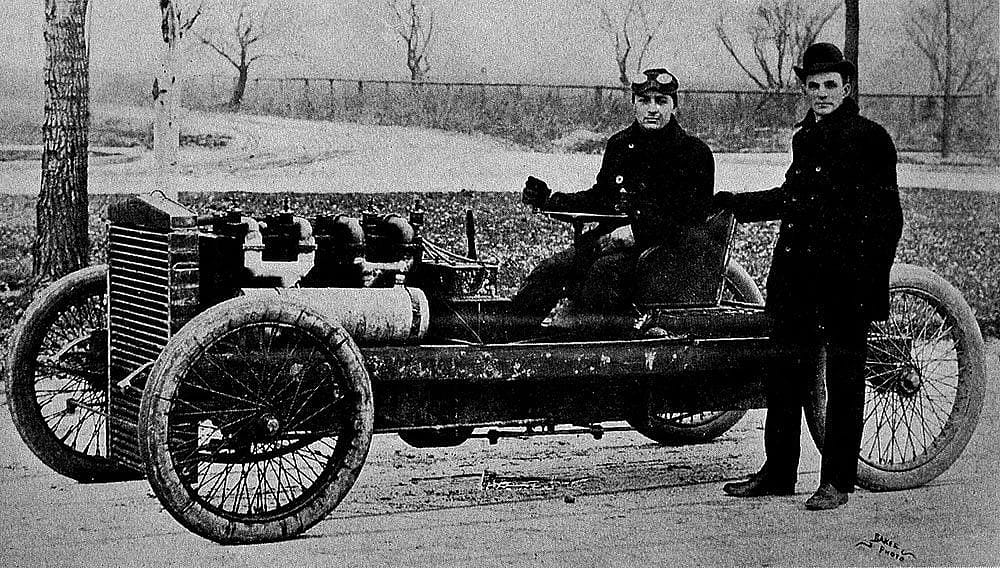

Another characteristic that both industrialists shared was the love of invention. Both Colt and Ford had lesser-known, sideline inventions that they developed. Colt worked on waterproof cartridges, submarine batteries and explosive harbor-defense systems, while Ford developed race cars and promoted aviation by developing the Tri-Motor airplane. Both men built mansions that took opulent architecture to new heights. Today, Colt’s Armsmear and Ford’s Fairlane are museums, each dedicated to the forceful, formative voice that gave rise to America’s industrial dominance.

Post 095

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.