Icon of the American West: Golden Eagle – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2015

Golden eagle: Icon of the American West

The Draper Natural History Museum’s ongoing exploration of our regional symbol and its environment

By Dr. Charles R. Preston

“There she goes, and she’s flying right toward you!”

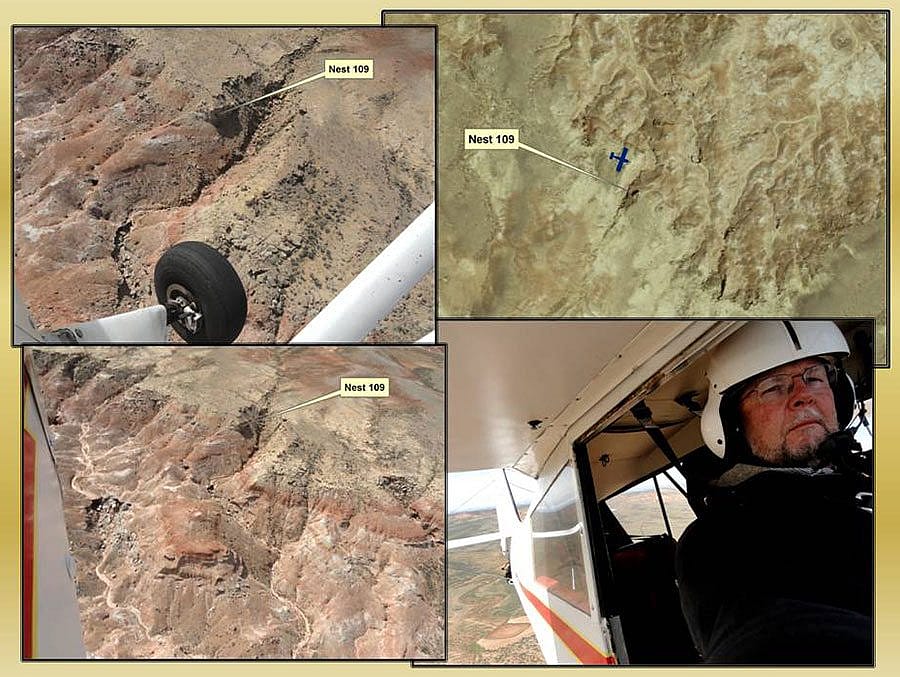

The shout came from Nate Horton, a fourth-year summer research assistant working on the Draper Natural History Museum’s long-term golden eagle research project in Wyoming’s Bighorn Basin. Nate had been approaching the recently fledged eagle from above the ridge where the big, chocolate-brown bird was perched. Volunteer Richard Jones and I were in a sagebrush flat below, hoping the eagle would land nearby. Richard has been conducting nest surveys, producing computer-generated maps, and assisting with all aspects of the project since 2009. Together, the three of us have developed a technique for capturing young eagles soon after they’ve left the nest and begun flying on their own. We are thus able to capture and band eagles of known nest origin without invading the nest.

Soon after the young eagle touched down in the sagebrush flat, I had her gently, but snugly, in hand with a leather hood covering her eyes. A hood, specially designed and fitted for an eagle, blocks the bird’s view and reduces stress. We found a shady spot where we could weigh, measure, and assess the bird’s health. Then, we placed an identification band around each leg and released her in a protected niche along the sandstone ridge where we first spotted her. She is one of more than a dozen fledgling eagles we banded in 2014.

Since the project’s inception in 2009, it continues to grow in importance each year. Researchers, observers, bird enthusiasts, and scientists have increasing concerns about the decline of sagebrush-steppe habitat through much of the American West, as well as escalating threats to golden eagle populations in some areas. Although we focus on golden eagles, we designed our study to provide insights into the broader effects of environmental change on the structure and function of sagebrush-steppe environments. Thus, the golden eagle provides a convenient barometer to detect and measure environmental change.

Both golden and bald eagles hold a highly revered place in our national history and culture. They have been awarded special status and protections under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (enacted 1940 and subsequently amended several times) and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (enacted 1918 and subsequently amended several times). The bald eagle was once included on the Endangered Species List due to dramatic population declines related to the widespread use of DDT and similar pesticides. These pesticides became concentrated in the bodies of insects and in aquatic environments. Predators such as bald eagle, osprey, and peregrine falcon were especially vulnerable because of their position high in these food chains. Thanks to additional protections and costly, active management efforts under the Endangered Species Act, the bald eagle has recovered. The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service removed the bald eagle from the Endangered Species List in 2007.

However, DDT does not significantly affect golden eagles because they prey primarily on terrestrial mammals. Historically, golden eagle populations have been relatively stable in western North America. In recent years, however, some golden eagle populations in the American West have been declining, and there are new, widespread, and significant threats on the horizon. In addition to its cultural status, the golden eagle plays an important role in ecosystems by preying on rodent and rabbit populations, and scavenging large animal carcasses. Therefore, it is important to understand golden eagle ecology and threats to its future. In that way, we can purposefully avoid unnecessary disturbance of ecosystem function and the drastic step of listing our other iconic American eagle as endangered.

As we have reported in several earlier issues of Points West and other venues, the Draper Natural History Museum is conducting an extended study of golden eagles in the area of the Bighorn Basin located within the northeastern portion of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. To provide perspective on our work, it is useful to explore the basic golden eagle natural history, and the current status and threats to this iconic species.

The golden eagle is one of the most widespread and best-known raptors, or birds of prey, in the Northern Hemisphere. It was once fairly common in large stretches of Eurasia, North America, and North Africa, but has declined or been eliminated from landscapes heavily populated by humans or converted to agriculture. The golden eagle is highly valued by falconers, and hunters sometimes train eagles to pursue and kill foxes, gray wolves, and other large prey. Because of its size, power, and hunting ability, the golden eagle has been highly revered through history by many cultures. It adorns the flags of several nations, and Native Americans widely use golden eagle feathers and parts in ceremonies and apparel. In contrast, the golden eagle has also been greatly maligned and persecuted for killing domestic sheep, reindeer, and other livestock in various parts of its range.

As in most raptors, female golden eagles are larger than males. A large female may sport a wingspan of up to seven and one half feet and usually weighs between ten to fourteen pounds. A golden eagle captured with a full crop and banded in Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest, however, weighed a record-breaking sixteen pounds. The great eagle is best adapted to hunting in large, open, or semi-open environments, and typically avoids large tracts of developed and agricultural lands. It is also largely absent from heavily-forested areas and true deserts with less than eight inches of precipitation.

In North America, the golden eagle is an apex predator (an animal with no natural predators) in native grasslands, sagebrush-steppe, alpine tundra, and other large expanses of mostly open environments—especially those with high cliffs or other elevated perch and nesting sites nearby. The golden eagle once nested widely in open marshes and near large burns in the Appalachians, but is absent or very rare as a breeder now in the eastern United States. The species still breeds in portions of eastern Canada and migrates south through the eastern United States. Golden eagles breed through much of western North America from Alaska to Mexico. In fact, the greatest density of golden eagles anywhere in the world occurs in western Canada and the western U.S., and this magnificent bird is widely renowned as an icon of the American West. Nonetheless, the number and range of golden eagles have declined in some areas of the West during recent decades.

Some North American eagles are still illegally shot, poisoned, and trapped. The greatest current threats, though, to eagle populations in the American West relate to habitat change caused by our expanding human footprint. In some areas, invasive cheatgrass, introduced to this continent from Eurasia more than a hundred years ago, is altering the natural fire regime and nature of native grassland and shrub-steppe habitats. Cheatgrass cures early in summer, setting the stage for increased wildfire occurrence. Because cheatgrass survives and even thrives with frequent fires, it replaces native vegetation and affects prey availability and thereby, the ability of the landscape to support eagles and other native wildlife.

Recently, media reports have brought much attention to the impacts on golden eagles of the rapidly growing numbers of wind farms. Eagles are among many bird species that are killed by flying into the blades of wind turbines. A recent paper appearing in the peer-reviewed Journal of Raptor Research reported that seventy-nine golden eagles were killed at thirty-two wind farms in ten states between 1997 and 2012—with sixty-seven of these mortalities occurring since 2008. The authors did not include the massive Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area in California in this study, and consider the number of documented mortalities to be a substantial underestimate of actual eagle deaths at wind facilities.

In 2009, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service issued regulations under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act that allowed some lethal “take” and disturbance of golden eagles under a formal permitting process. The Secretary of the Interior is accountable for that process of permitting take of eagles “necessary for the protection of other interests in any locality” if the take is “compatible with the preservation of the bald eagle or golden eagle.” The intent is to ensure no net-decrease in the number of breeding pairs of eagles within regional geographic management units.

The American Bird Conservancy has filed suit against the federal government over a rule allowing wind energy companies to obtain thirty-year permits to kill or injure eagles, thus extending permit limits by twenty-five years. The lawsuit highlights a significant environmental conundrum related to the emergence of wind energy. While wind energy reduces the need for fossil fuel-powered electricity and associated air and water pollution, wind turbines also disrupt wildlife habitats and may kill large numbers of birds and bats.

Our study of golden eagles in the Bighorn Basin has therefore taken on new significance as we provide information on the status and dynamics of a substantial regional breeding population of a species under heightened scrutiny by federal managers, commercial interests, and the public at large. In addition to our regular research protocol in 2014, we collaborated with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to place four satellite transmitters on eagles fledged from nests in our study area. Many recognize our study as a model program to better understand the factors that impact golden eagle reproduction in the American West.

Thus far, we’ve been able to document wide year-to-year fluctuations in golden eagle reproductive effort and success tied closely to cyclic abundance and availability of cottontail rabbits. Although nesting golden eagles prey on other species, cottontails comprise an overwhelming percentage of the diet in our area. This is in contrast to other areas of the West, where ground squirrels, marmots, or jackrabbits make up the majority of golden eagle nesting diet. In addition to cottontails, nesting eagles in our study area also regularly prey on ravens, magpies, rattlesnakes and bullsnakes, pronghorn fawns, and a variety of small birds and mammals.

Individuals often assume that golden eagles prey heavily on sage grouse, but we have identified only a handful of sage grouse remains from our analyses of more than six hundred prey items collected from nests during the past six years. We have found a surprising number of remains from great horned owls among prey items we’ve collected.

We’ve discovered quite a difference in productivity (the number of young produced) among individual golden eagle nesting territories. The most highly productive territories include fewer roadways and off-road vehicle (OHV) trails, and a patchwork of open and densely vegetated landscape. Long-time eagle researcher Karen Steenhof and her colleagues recently examined more than forty years of data collected in southwestern Idaho. Their study concluded that golden eagle nesting territories in areas where OHV use has increased were less likely to be productive than those territories in areas that included little or no motorized recreation. The link we found between productivity and patchwork landscapes makes sense in that the mixture of dense vegetation and open ground provides ample structural habitat for cottontails, but also includes relatively barren areas where moving rabbits are vulnerable to capture from above.

As we continue our research in the Bighorn Basin, we plan to expand our efforts into winter to determine movements of our marked birds, as well as the breeding origin of eagles overwintering in the Basin. From past banding records and satellite tracking, we know that some birds that overwinter in our region are from breeding populations as far away as Alaska. Beginning in November 2014, we began to trap and band adult and juvenile eagles, and use remote cameras to record the presence of marked eagles from local and continental populations.

Finally, I am pleased to acknowledge the critical financial support provided to this project by the Bureau of Land Management, Wyoming Wildlife—The Foundation, Rocky Mountain Power, Nancy-Carroll Draper Foundation, and many contributors to the Draper Natural History Museum’s Cal Todd Memorial Research Fund. The Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Geological Survey—Bird Banding Laboratory, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, HooDoo Ranch, and Monster Lake Resort have been especially helpful with logistical support.

I especially want to thank our loyal Golden Eagle Posse citizen science volunteers, who have assisted with nest monitoring and data collection since 2009. Their great work and enthusiasm continue to provide inspiration. You can check out some their contributions and comments at wyofile.com/kelsey-dayton/volunteers-help-document-bighorn-basins-golden-eagles. For more reading on the subject, contact the editor at [email protected] and request “Selected References on Golden Eagles, Points West, spring 2015.”

About the author

A prolific writer and speaker, Dr. Charles R. Preston serves as the Willis McDonald IV Senior Curator of Natural Science at the Center’s Draper Natural History Museum. He is an ecologist and conservation biologist who explores the influence of climate, landscape, and human attitudes and activities on wildlife, and is widely recognized as a leading authority on wildlife and human-wildlife relationships in the Greater Yellowstone region.

Post 098

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.