Adversity and Renewal – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West in Winter 1999

Adversity and Renewal

By Emma I. Hansen

Curator Emerita, Plains Indian Museum

A long time ago my father told me what his father told him, that there was once a Lakota (Sioux) holy man, called Drinks Water, who dreamed what was to be; and this was long before the coming of the Wasichus (white men). He dreamed that the four-leggeds were going back into the earth and that a strange race had woven a spider’s web all around the Lakoms. And he said. “When this happens, you shall live in square gray houses in a barren land, and beside those square gray houses you shall starve.” ˜ Black Elk, Oglala Lakota [1]

In 1931, Black Elk recounted this prophecy about the end of the buffalo and the Lakota lives as free buffalo hunters of the Plains. He had witnessed the changes brought about by confinement on the reservation, influences of missionaries and government agents, disease, and starvation that threatened the physical and cultural survival of the Lakota. Remarkably, the Lakota endured and through their resilience and creativity built a new way of life while renewing important cultural traditions. Adversity and Renewal, one of the galleries of the Plains Indian Museum, tells the story of this survival and cultural revitalization of the Lakota and other Native people of the Plains.

The heart of this gallery is a log house constructed to resemble those built at Pine Ridge during the transitional reservation period (ca. 1890–1920). The home is outfitted with a mixture of Lakota and Euro-American furnishings, and household objects. Through this display with its Native and non-Native objects, museum visitors learn that the Lakota way of life was not abandoned for another through a process of assimilation. New elements were adapted at the same time that traditional arts, ideals, and beliefs were maintained.

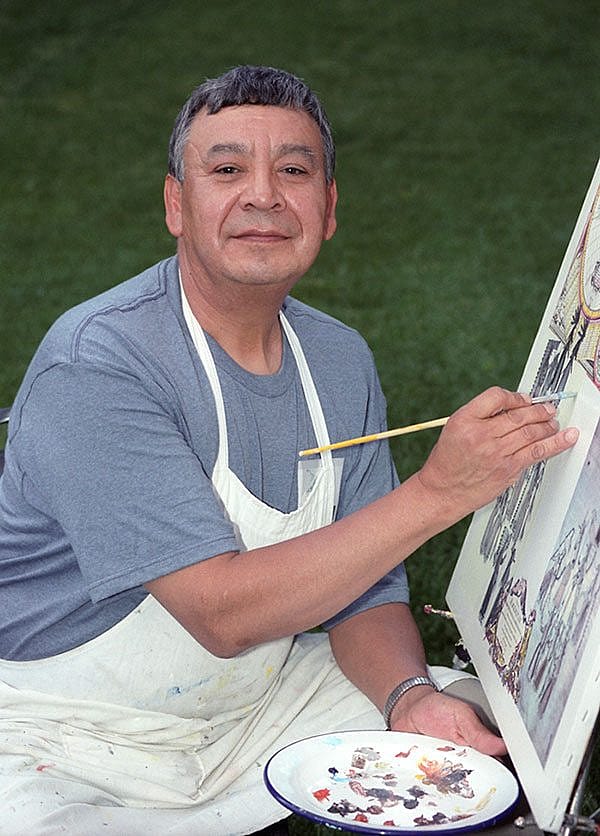

Arthur Amiotte, Lakota artist and scholar and a founding member of the Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board, consulted on the completion of the cabin and generously providing personal and family belongings and photographs to bring the exhibition to life. He has described his art as emanating from his experiences in growing up in such a home:

“My early experiences of ‘real culture’ began with my grandparents. My art makes a statement about native existence – not of a mythical, romantic Indian riding across the Plains, but rather the story of the Indian today who was born into a reservation home. For example, we lived in a log house on the reservation, drank water from the creek, and made wastunkala (dried corn) and dried berries for wojapi (pudding). We were allowed to experience life through all the senses, growing into the age of reason, where one is able to understand as an adult the true meaning of things.” [2]

During the late 1800s to early 1900s, after reservations had been established for the Plains tribes, an ironic flowering of tribal arts occurred. Just as the people confined to the reservations seemed to have reached the nadir of their existence, their creativity continued to be expressed through innovation in design and use of materials. Traditional porcupine quillwork was used in combination with glass beads, wool trade cloth, fabric, tin cones, silk ribbons, brass bells, and other new materials. During the 1890s, Lakota and Cheyenne women began beading pictographic designs of warriors, horses, buffalo, deer, elk and often the American flag on clothing and pipe bags.

They also developed a new style of decoration in which entire objects were covered in beadwork. As women produced fully beaded moccasins and men’s vests and even covered glass bottles with beadwork, it was said, “Sioux women beaded everything that didn’t move.” [3]

The reasons for this flowering of Plains arts during the early reservation period are not fully understood. Scholars have suggested that women, once they were settled on the reservations, simply had more time to produce the decorated clothing and other materials that characterized this period. The motivations for this artistic embellishment, however, have deeper roots. Beginning in 1880, federal authorities had banned the Sun Dance and other religious ceremonies arresting traditional leaders and other participants. On the reservations, Native people struggled to maintain their tribal identities while government agencies, schools, and missionaries attempted to convince them to set aside their languages, beliefs, ceremonies, and community life. Clothing made for special occasions and other objects decorated with tribal designs became increasing important as a means of maintaining Native identities.

The log house in Adversity and Renewal features such examples of Lakota arts as well as patch work quilts, embroidery, fringed shawls, and trade blankets. Audio based upon the remembrance of Olive Louise Mesteth, Arthur Amiotte’s mother who lived with her grandparents Standing Bear and Louisa Standing Bear, describes life in such a cabin centering around gardening, beading, sewing, ceremonies, dinners, and visiting.

The Standing Bear Home exemplified the Lakota ideals of hospitality, respect for elders, and generosity through sharing of family goods with the community. Through such shared experiences, relationships were built between generations that allowed the Lakota to move beyond the destructive influences of the reservation.

According to Amiotte:

“My early bonding with my grandparents and the elders on the reservation instilled in me the conscious ness of belonging to a group. Even as a boy, I helped with the chores of gathering roots and berries and hauling wood, and I helped sort beads for the beadmakers. Those six years with my grandparents have influenced my entire life.” [4]

Notes

Notes

- In John G. Neihardt, Black Elk Speaks (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 9 – 10.

- In Arthur Amiotte, This Path We Travel: Celebrations of Contemporary Native American Creativity (Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing and the Smithsonian Institution, 1994), 26.

- In Maria N. Powers, Oglala Women: Myth, Ritual and Reality (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986), 137.

- Amiotte, 26.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.