On the Trail of a Bear Named Wahb – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West in Spring 2009

On the Trail of a Bear Named Wahb: Two Professors on a Bear Hunt

By Jeremy Johnston

Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Western American History

In the summer of 2008, fellow Northwest College professor Burt Bradley and I set off on a cool, summer morning to trail the famed renegade grizzly bear, Wahb. Ernest Thompson-Seton detailed the exciting life of the fictional Wahb in his book The Biography of a Grizzly, which he wrote in 1899 shortly after visiting A.A. Anderson’s Palette Ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming. This account first appeared as three installments in the pages of Century Magazine, and in 1900, the three articles appeared together in print as a small book.

Seton’s story follows the exploits of Wahb from his birth in the upper Greybull River Valley of Wyoming to his death in Yellowstone National Park. Although Seton’s tale of Wahb is characterized as fiction, Seton based many of Wahb’s experiences on true grizzly bear stories. The setting of The Biography of a Grizzly was also based on real geographical features that Seton visited during his trip to Yellowstone in 1897 and to the Palette Ranch in 1898.

Many of those locations remain relatively unchanged since Seton first visited them over one hundred years ago. We hoped to learn more about Seton and his imaginary bear by visiting these spots. Our goal was to grasp a sense of place in relation to Wahb’s story and instill in us a better understanding of the history and legacy of grizzly bears in the Yellowstone ecosystem.

Hitting the trail

Ironically, to begin our travels, Burt and I focused on the place where Wahb ended his life. After years of hardship and struggle, Wahb could no longer endure the pain caused by his advanced age and his past wounds. After more than twenty years of fighting other animals, weather, and humans, Wahb concluded that his pain no longer allowed him to defend his territory. He traveled from his home range, centered in the Greybull River Valley, and walked to Death Gulch in the Lamar Valley in Yellowstone National Park. The park provided Wahb a peaceful refuge, a place where he was safe from his most dangerous foe, man.

Seton wrote, “In the limits of this great Wonderland…no violence was to be offered to any bird or beast, no ax was to be carried into its primitive forests, and the streams were to flow on forever unpolluted by mill or mine…this was theWest before the white man came.” Wahb and other species of wildlife discovered that Yellowstone provided a sanctuary. “They soon learned the boundaries of this unfenced Park,” Seton explained. “They show a different nature within its sacred limits. They no longer shun the face of man; they neither fear nor attack him; and they are even more tolerant of one another in this land of refuge.”

Despite Seton’s description of the park as a place where man and beast observed a neutral stance, Burt and I cautiously watched for any sign of Wahb’s living counterparts as we hiked up the trail along Cache Creek (a tributary of the Lamar River ) towards Death Gulch.

A grizzly end

This region, which provided Wahb refuge from the depredations of man, also promised him the ultimate comfort of an everlasting peace and complete freedom from pain and suffering. Seton closed the story with Wahb’s death from poisonous fumes released from the geothermal area known as Death Gulch.

At the time Seton wrote his account of Wahb, scientists still puzzled over this strange and macabre feature. Animals that strayed too far up this gulch seemed to be poisoned by the pungent fumes from the geothermal fissures in the gulch. As more and more animals were asphyxiated, grizzly bears, looking for an easy meal, also entered the gulch and succumbed to the poisoned air.

Seton described Wahb’s entry into the deadly gulch: “A Vulture that had descended to feed on one of the victims was slowly going to sleep on the untouched carcass. Wahb swung his great grizzled muzzle and his long white beard in the wind. The odor that he once had hated was attractive now. There was a strange biting quality in the air. His body craved it. For it seemed to numb his pain and it promised sleep….” The great bear continued walking into the gulch and “the deadly vapors entered in, filled his huge chest and tingled in his vast, heroic limbs as he calmly lay down on the rocky, herbless floor and a gently went to sleep, as he did that day in his Mother’s arms by the Graybull [sic] long ago.

Walter H. Weed, a member of the 1888 United States Geological Survey expedition of the Yellowstone region led by Arnold Hague, claimed he discovered this unusual feature that caused Wahb’s death. In Science, Weed noted the site was easily reached by following an “old elk trail” up Cache Creek. When exploring the region, he wrote, “…the gaseous emanations are very striking and abundant.” Today the “old elk trail” is well-marked and well-traveled, but the pungent odor from the geothermal region remains.

As we worked our way up Cache Creek, just short of Death Gulch, we encountered a hot spring boiling up in the middle of the creek. This is now known as Wahb Springs, honoring Seton’s fictional bear. Weed also noticed this spring and wrote, “…the great amount of gas given off at this place is easily appreciated, but equally copious emanations may occur from the deposits and old vents near by….”

What is that stench?

Burt and I both agreed with Weed’s observation. The strong, bitter, sulfurous smell permeated the air that, until that moment, had been of the fresh, mountain variety. At times, the odor was so strong, it nearly took our breath away. On the other hand, we doubted the accuracy of our sense of smell as we wondered if the strong odor was a product of our heightened imaginations, excited by finding the place where the great grizzly bear Wahb ended his life.

Continuing up Cache Creek, we found the deep-scarred ravine of Death Gulch. When Weed discovered the gulch in 1888, he and his companions found six dead bears, an elk carcass, and scores of smaller game animals littering the rocky floor. One of the bear carcasses, a large silvertip grizzly, “was carefully examined for bullet holes or other marks of injury,” wrote Weed, “but [the grizzly] showed no traces of violence, the only indication being a few drops of blood under the nose.”

After examining the carcasses and exploring the upper reaches of the gulch, Weed theorized, “It was apparent that these animals, as well as the squirrels and insects, had not met their death by violence, but had been asphyxiated by the irrespirable gas given off in the gulch.”

Later visitors to Death Gulch also noted the presence of dead bears. In 1897, T.A. Jagger visited the site, accompanied by Dr. Francis P. King, and documented his trip in an article for Appelton’s Popular Science Monthly. Jagger and King climbed “through this trough, a frightfully weird and dismal place, utterly without life, and occupied by only a tiny streamlet and an appalling odor.” As the men worked their way up the gulch, they noticed “some brown furry masses lying scattered about the floor of the ravine…. Approaching cautiously, it became evident that we had before us a large group of huge recumbent bears.”

Jagger and King counted eight bear carcasses, seven of which were grizzly bears. Fearful, Jagger tossed a rock onto one of the carcasses to ensure the bear was dead. “Striking him on the flank,” wrote Jagger, “the distended skin resounded like a drumhead, and the only response was a belch of poisonous gas that almost overwhelmed us.” Continuing their investigation of the other bears, “One huge grizzly,” noted Jagger, “was so recent a victim that his tracks were still visible in the white, earthy slopes, leading down to the spot where he had met his death.”

Like Weed, Jagger concluded that “there can be no question that death was occasioned by the gas…attested by the peculiar oppression on the lungs that was felt during the entire period that we were in the gulch…I suffered from a slight headache in consequences for several hours.” More disturbing to Jagger and King was the fact that a small stream of water entering Cache Creek “trickles directly through the worm-eaten carcass of the cinnamon bear—a thought by no means comforting when we realized that the water supply for our camp was drawn from the creek only a short distance down the valley.”

Clearly, these two accounts of Death Gulch alone would inspire Seton’s ending of The Biography of a Grizzly. Possibly Seton visited the site in 1897 when he stayed at Yancey’s Hotel, located a few miles to the west of Death Gulch. Seton obviously modeled Wahb’s death after the victims of Death Gulch and accurately described the noxious odor permeating the air surrounding this unusual geothermal area.

Burt and I stood on the other side of Cache Creek, scanning Death Gulch from its lower reaches to the top, noting the same strong odor described by Weed and Jagger. We did not notice any bear carcasses in the gulch, or for that matter any bear tracks, but the smell that Weed and Jagger described was present and at times overwhelming. The combination of petrified trees, dead trees, and the unusual extinct and active geothermal formations enthralled us. Despite the lure of exploring the gulch, we both decided that we did not want to get our feet wet by crossing the creek to enter Death Gulch; nor did we want to tempt our fates by tracing the last few tracks of Wahb’s final trail. Instead, we sat down and ate our lunch while contemplating the sublime scenery of Cache Creek and the mysteries of Death Gulch—safely on the other side of the creek.

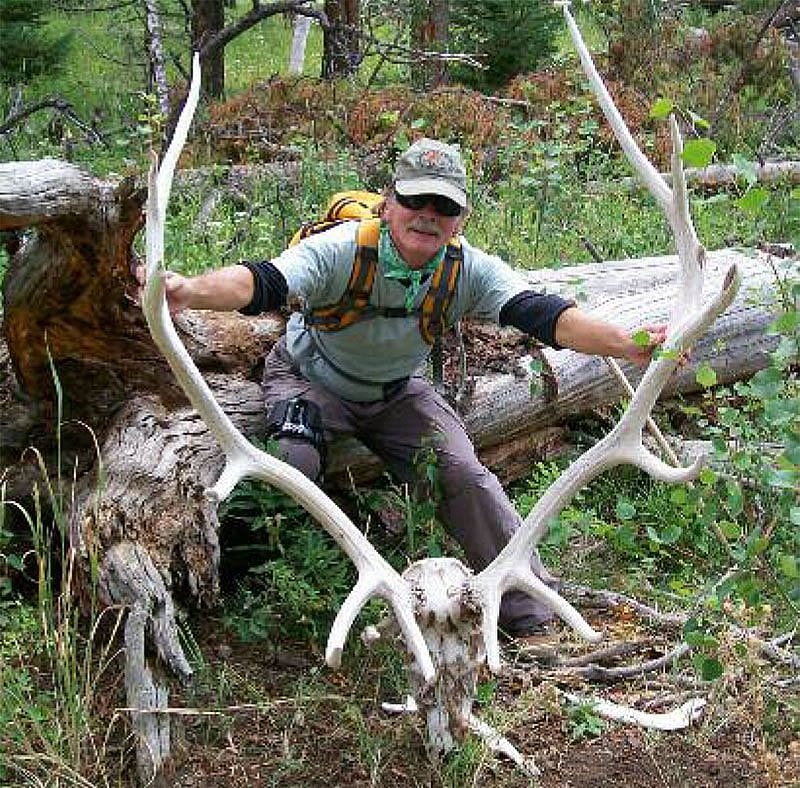

As we hiked back to the trailhead and began our trek home, we discovered the antlers and bones of a very large bull elk, not far from Death Gulch. Ironically, it appeared that winter and advanced age had exacted this toll. The mysterious gulch was not the culprit this time.

On the trail again

After following Wahb through Yellowstone Park, Burt and I agreed we would continue trailing him, this time to his home terrain on the upper Greybull River. We set out early in the morning to resume tracking Wahb’s trail.We started where Colonel Pickett wounded Wahb and killed his mother and three siblings in revenge for the mauling of his prized bull by Wahb’s mother. Not only did this event physically wound Wahb in his hind leg, it marked the beginning of Wahb’s war against mankind to appease his desire for revenge.

Our route took us through Cody where we sniffed the sulfurous smell of DeMaris Hot Springs—on the western edge of town—mixed with smoke from the wildfires burning along the North Fork of the Shoshone River last summer. We remembered another scene from The Biography of a Grizzly where Seton described Wahb using a hot spring to ease his pain. Some later believed that site to be DeMaris Hot Springs:

There are plenty of these sulphur-springs in the Rockies, but this chanced to be the only one on Wahb’s range. [Seton described Wahb climbing into the springs and pondering the mystery of the warm water.] [Wahb] did not say to himself, “I am troubled with that unpleasant disease called rheumatism, and sulphur-bath treatment is the thing to cure it.” But what he did know was, “I have dreadful pains; I feel better when I am in this stinking pool.” So thenceforth he came back whenever the pains began again, and each time he was cured.

Seton certainly learned about the existence of DeMaris Hot Springs when he visited this region in 1898, why some conclude this site to be the setting for Wahb’s warm water treatments. However, Seton later noted he discovered the hot pool that inspired this scene in the Wind River Valley of Wyoming; thus, Wahb’s pool may be Washakie Hot Springs.

Another possibility is Thermopolis Hot Springs, which Seton may have also heard about during his visit. Although we may never know which specific hot springs inspired Seton, clearly he had many choices. Today, all of these springs continue to provide comfort, not to bears, but to many humans seeking alternative cures for various ailments. Burt and I wondered how Wahb would look today sliding down the waterslides at Thermopolis, Wyoming!

Fusing fact and fiction

Leaving Cody, we soon traveled southwest to Meeteetse, Wyoming, where we followed the Greybull River, traveling back in time as each spot told the tale of Wahb. Seton described one of Wahb’s revengeful acts that occurred along the banks of the river. When two settlers named Jack and Miller built a claim shanty in Wahb’s domain, he naturally decided to investigate. When the great bear arrived, Miller was away, but Wahb found Jack near the stream fetching water. Jack raised his rifle and shot at Wahb hoping to kill the bear, or at the very least, drive the large bear away.

Pained by the shot but still very much alive, Wahb quickly fell upon the trapper. After defending his territory, Wahb retreated to the more isolated regions of his haunt. Meanwhile, the mortally wounded trapper crawled back to his cabin and penned the following message, “It was Wahb done it. I seen him by the spring and wounded him. I tried to git on the shanty, but he ketched me. My God, how I suffer! [signed] JACK.” When the other trapper tracked Wahb down to avenge his partner’s death, Wahb killed him, too. In the end, Miller’s and Jack’s cabin slowly rotted into the ground.

Seton wrote this story to show the strength and ferocity of the grizzly bear. This scene of Wahb’s life was clearly based on past bear encounters and specific settlers of the region. The name of the trappers in Seton’s account, Jack and Miller, more than likely came from two creeks in the Yellowstone region. Jack Creek, located in the upper Greybull Valley, is named after an early trapper, Jack Wiggens. Seton may have selected the name Miller from Adam “Horn” Miller, who also has a creek in Yellowstone National Park named after him.

Seton met Horn Miller’s partner, “Old Pike” Moore at Yancey’s Hotel in Yellowstone. Writing for Recreation, Seton noted that Moore and Miller “came into Montana to make their fortunes. They have made them, or have been with one jump of making them, many times since then; and they are still pegging away, hopefully, together.” In 1913, Miller died and was buried in the Cooke City, Montana, cemetery.

The assault on Jack in Seton’s account is eerily similar to a historical incident that occurred in the Greybull River Valley. In 1892, a grizzly bear attacked Phillip H. Vetter. Tacetta B. Walker later wrote in her book Stories of Early Days in Wyoming that the bear which attacked Vetter lost two toes from stepping on a steel trap, similar to the fictional Wahb who lost one toe to a trap. Vetter survived long enough after the attack to crawl back into his cabin, patch up his mangled arm, and then write a note describing his plight, “All would have been well had I not gone down the river after supper…should go to [Otto] Franc’s but too weak…. It’s getting dark…. I’m smothering… I’m dying.” According to A.A. Anderson, who also described the incident in his autobiography, Vetter wrote “My God, how I suffer!” Vetter was buried in the Greybull Valley. Later, Vetter’s body and tombstone were relocated to Old Trail Town on the west edge of Cody.

Where the hate began

Meanwhile, Burt and I finally reached our destination: the mouth of Rose Creek, where Wahb’s hatred of man began. According to Seton’s account, Colonel Pickett, a Civil War veteran and early rancher, killed not only Wah’s mother but also three siblings. Pickett managed to wound the young cub, Wahb, an injury that would instill a lifelong hatred for man for years to come. Seton wrote that the site from that day on was known as Four Bear, to honor Pickett’s hunting success.

Once again, Seton based this fictional tale on a factual incident. Colonel Pickett did indeed kill four bears on the evening of September 13, 1883: three adult grizzlies and one grizzly cub. One bear escaped Pickett’s rifle—not a cub, but a full-grown grizzly. A group of surveyors who were camped near the kill site renamed Rose Creek “Four Bear Creek.” (Later, though, Rose Creek, which flows south into the Greybull River, regained its original name, and the name Four Bear Creek was applied to another creek in the same proximity but which flows north into the Greybull River.)

Numerous bears had been attracted to the area after a dog spooked a number of cattle belonging to Otto Franc, a cattleman who established the Pitchfork Ranch. The herd stampeded into a deep ravine that cradled Rose Creek, and some fifty cattle died crossing the creek in their mad haste to escape the dog. Their rotting carcasses became a natural attractant to the bears in the area and thus drew the bear hunter, Colonel Pickett.

Burt and I found it ironic that the headquarters of the Pitchfork Ranch now stand on the site where those fifty dead cows attracted Pickett’s prey. We discovered another irony when we explored present-day Four Bear Creek: along its banks is the Four Bear oilfield. Here we read a sign warning us of noxious gases in the area. It seemed strange that after visiting Death Gulch where Wahb asphyxiated himself, we found posted warnings of noxious gas fumes alongside a creek named for the very event that Seton claimed made Wahb a man-killer. Sometimes history and literature have an unusual way of impressing themselves on the landscape.

The Palette Ranch: Wahb’s birthplace

Leaving the Four Bear oilfield, Burt and I continued back in time as we traveled down the gravel road along the Greybull River. We approached the Palette Ranch near Piney Creek, the area where, according to Seton’s book, Wahb was born. This is also true in a more literal sense because it was here at the Palette Ranch that Seton first dreamed up his story about Wahb.

After traveling from Jackson Hole,Wyoming, through the Thoroughfare region southeast of Yellowstone, Seton and his wife met A.A. Anderson, the founder of the Palette Ranch, in 1898. Seton’s wife, Grace, recalled the scenic setting of the Palette Ranch in her book, A Woman Tenderfoot. Of the ranch, she penned, “there is no spot in the world more beautiful or more health giving.” The ranch “is tucked away by itself in the heart of the Rockies, 150 miles from the railroad, 40 miles from the stage route, and surrounded on the three sides by a wilderness of mountains.” Mrs. Seton also described the luxurious trappings of the main ranch house and wrote “the message of good cheer that steamed in rosy light from its windows seemed like an opiate dream.”

Inside the ranch house, the Setons discovered “a large living room, hung with tapestries and hunting trophies where a perfectly appointed table was set opposite a huge stone fireplace, blazing with logs.” Anderson served his guests “a delicious course dinner with rare wines, and served by a French chef.” After dinner, the Setons retired to a room that “was a wealth of colour [sic] in Japanese effect, soft glowing lanterns, polished floors, fur rugs, silk furnished beds and a crystal mantelpiece (brought from Japan) which reflected the fire-light in a hundred tints.” Even the bathroom impressed Grace for “it was a room that would be charming anywhere, but in that region a veritable fairy’s chamber.” Grace concluded that, “Truly it is a canny Host who can thus blend harmoniously the human luxuries of the East and the natural glories of the West.”

Sitting around the warm fire of the luxurious Palette Ranch house, Anderson later recalled, “I told Mr. Seton about an unusually large grizzly bear that had been frequenting the country about my ranch for many years and had been most destructive to my cattle.” Anderson reasoned these depredations resulted from only one bear because he “knew this by the track, which measured thirteen inches in width…. I knew this was an unusually large bear not only by the size of his track but by the depth it would sink down into the soft earth.”

After hearing about Anderson’s problem bear, and also drawing upon his experiences in Yellowstone in 1897—the great number of bears feeding off the trash piles surrounding the Fountain Hotel and a possible visit to Death Gulch—Seton weaved together his narrative about the great grizzly bear Wahb. What better place to set the birth of Wahb than the upper reaches of Piney Creek that flows next to the Palette Ranch?

The death of Wahb

Ironically, not only is the Palette Ranch the site of the fictional and literary birth of Wahb, it is also the supposed site of the “real” Wahb’s death. Anderson later said that even though in Seton’s story Wahb killed himself in Death Gulch, “This is poetic license, as Wab [sic] met a different end.” In 1915, after years of chasing the elusive Wahb, Anderson finally encountered the great bear pursuing a female bear. Anderson wrote, “This love affair was the cause of his destruction.”

After killing Wahb’s mate, Anderson saw the great bear “crossing a small opening among the trees at a fast walk.” As Anderson told the story, “I took aim and fired…. I found [Wahb] dead only a few yards from the spot where I had shot at him…[;] his skin now decorates my studio.” Not to be outdone by Colonel Pickett, Anderson also claimed that on “the morning of the same day, I had been successful in killing two other grizzlies; a total of four grizzlies in one day.”

Time to ponder

Burt and I pulled off the road, and just below us, the Greybull River flowed rapidly toward the east. On the other side of the river, the sunlight highlighted the rooftops of the conglomeration of buildings of the Palette Ranch. A line of pine trees indicated the course of Piney Creek, meandering up to the gray soil of the treeless alpine region. There the creek bed revealed its presence with bright snow pack lining its channel.

Here Wahb entered the region that would be his domain, according to Seton. In the ranch house below, the literary Wahb was born as Anderson and Seton exchanged stories by the fire blazing in the large stone fireplace. It was also near here that Anderson supposedly killed the real Wahb. Burt and I took it all in, viewing a landscape that remained relatively unchanged for more than a hundred years—a landscape that continues to inspire creativity and generate wonder as it did for Seton.

As we drove home, we noticed a sign: “Grizzly Bear Area—Special Rules Apply.” Despite all the environmental and human threats, the grizzly has endured through the passage of time, and this region continues to be Wahb’s domain.

About the authors

Jeremy Johnston, Assistant Professor of History at Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming, when this article was written, is now the Center of the West’s Historian and Hal & Naoma Tate Endowed Chair of Western History, as well as Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody. Dr. Burt Bradley, then Associate Professor of English at Northwest College, is now Professor Emeritus.

Post 102

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.