Depictions of Women in Western Art – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West in Spring 1995

Depictions of Women in Western Art

By Sarah E. Boehme

Former Curator, Whitney Western Art Museum

“Oh, do you remember Sweet Betsy from Pike/Who crossed the wide prairie with her lover Ike?”[1] Those words open a well-known American folk song that celebrates the western emigration of a spunky female pioneer. Images in painting, sculpture and cultural artifacts have also commemorated the pioneering role of women who made the journeys which changed the West.

Western artists used the motif of women traversing the Plains in depictions of Indian culture as well. [Let’s] explore the ways women are portrayed in Western art, at once revealing a more prominent presence than previously thought and pointing to a restricted set of roles.

W.H.D. Koerner’s The Road to Oregon (Lone Travel, or Travel in Groups of a Few, As Andy Had Known It, Was Practically a Thing of the Past) presents a classic image of the pioneer woman, perched on a wagon seat with the billowing white of the covered wagon behind her. In this painting, done as half of a double-page spread illustrating a Saturday Evening Post story, the inclusion of women and children signaled the change occurring in the West. The journey across the land was no longer the solitary task of the mountain man or the explorer. Community replaced independence.

Another Koerner illustration reveals the way that these depictions had religious overtones. Koerner’s cover painting for the novel The Covered Wagon has become known as Madonna of the Prairie, a title which reinforces the association with sacred themes, signifying divine sanction of the journey.

Works of art often present an ideal vision, and that is certainly the case with most representations of women on the Oregon Trail. Although diaries written by women making the cross-country trip often record severe hardships, the paintings present an optimistic view. In the Koerner painting, The Road to Oregon, the men walk while the women ride, giving them a more protected role. In actuality, women often walked because the wagons were heavily loaded.

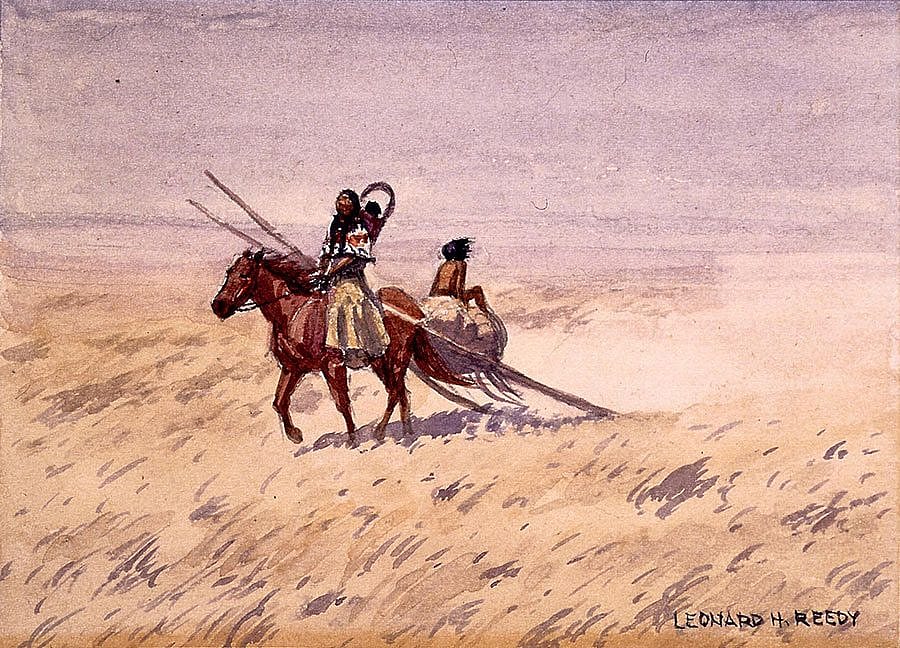

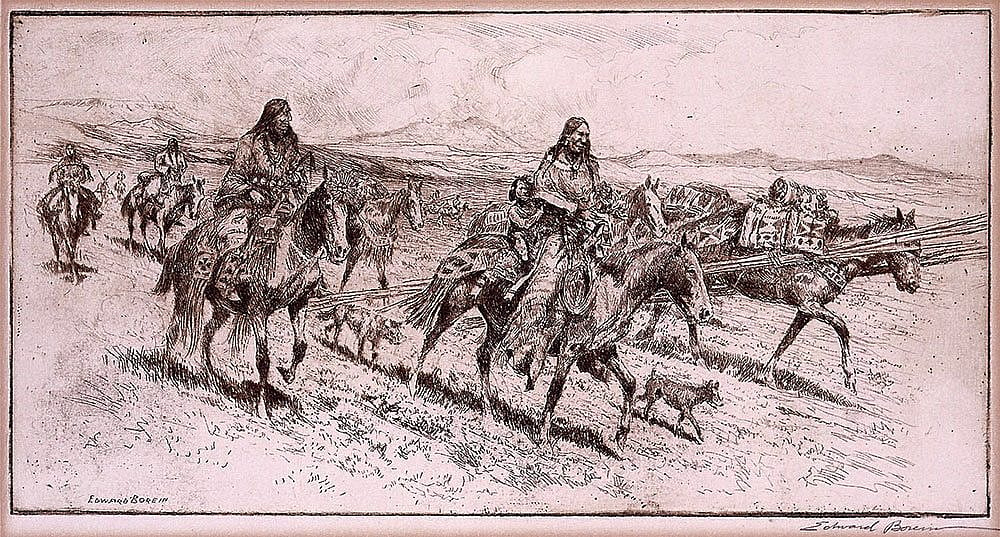

The duties of women were depicted somewhat differently in western art representations of Indian women crossing the Plains. An Indian woman with a travois, moving a family’s belongings, appears in such works as Edward Borein’s Blackfeet Women Moving Camp, No. 2 or Leonard Reedy’s Squaw with Travois.

The title of the Reedy watercolor may shed light on the significance of the image to an audience of its time. The demeaning word “squaw” was sometimes linked to a belief that the Indian race was a degraded one. In this belief system, the Indian women were seen as drudges. They were portrayed as having to labor, whereas white women were supposed to be sheltered.

Women in western American art also appear as paragons of beauty, as they have throughout the history of art. In the American West, the portrayals usually center on the Indian princess and the glamorous cowgirl. Due to Puritan influences, early American art has no tradition of depicting the nude, but exceptions sometimes appear in the paintings of Indian women. The otherness of the culture permitted latitude.

Beautiful Indian women play the role of helpmate for powerful white men, as in the story of Pocahontas, and become regarded as “princesses.” The historical person Sacagawea, who traveled with Lewis and Clark, blended several roles—helpmate to the explorers, mother to her young child, victim who is restored to her family. The combination of these roles may help to explain why Sacagawea is one of the most often portrayed women in American art.

The image of the beautiful cowgirl arose from Annie Oakley and the women who appeared in Wild West shows. In contemporary western art, the cowgirl has become an heroic figure, celebrating the active roles of women in the West.

Post 105

1. Sweet Betsy from Pike was probably written during the time of the California Gold Rush. See Songs of the West (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1991), pp. 30 – 31.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.