From Photograph to Painting – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West in Fall 2007

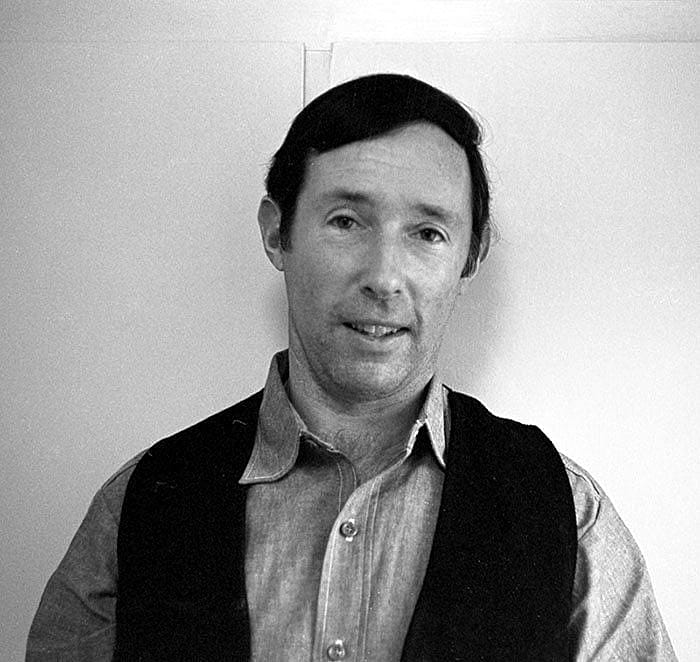

From Photograph to Painting: The Art of James Bama

By Thomas B. Smith

The realist portraits of cowboys, Native Americans, mountain men, and Cody locals rendered by Wyoming artist James Bama are recognizable to many visitors to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. However, few are aware of his monumental photography archive of the people of the East Yellowstone Valley. For more than thirty years, Bama has photographed subjects as references for his paintings, capturing a record of the inhabitants of Park County and Northwestern Wyoming. Ultimately, he has used his photographic material to become one of the most significant painters of contemporary western portraiture.

Bama’s use of photography began when he was a student at the Art Students League in New York. Frank Reilly, Bama’s principal instructor, had an amazing gift for teaching. Under Reilly’s tutelage, Bama concentrated on the basics of art including form, human anatomy, precise draftsmanship, and elements of composition, color, and depth.

Reilly also introduced Bama to photography as a means of enriching his painting material. Although many artists eschewed the use of photographs in the painting process as mechanical and contrived, Reilly and others found the medium a useful tool with which to recall detail.

Bama was among the first artists to use photography as a means to paint with precise detail—the wrinkles in a worn face, individual hairs on a subject’s head, or the intricacy of Native American beadwork. This new method infused his work with a realism some critics began to call “photorealism.”

Despite his reliance on photography as a reference, Bama does not consider himself a photorealist. His intention, he argues, is not to recreate photographs, but rather to render his subjects with photographic precision. Bama applies the fundamentals he learned from Frank Reilly’s classes to his easel painting. Using a Hasselblad camera, he photographs people as he finds them and in the best available light. He strives for a minimal background and focuses on his subject’s physical features and apparel.

After evaluating the proofs and deciding on the one(s) to use, Bama enlarges the image(s) to 11 by 14 inches. Referencing the photographs, he then produces a freehand contour sketch on tracing paper. The image is further developed into a lightly shaded working drawing.

Next, Bama creates the work’s color scheme by painting several small individual sketches. When deciding on the colors in his paintings, he disregards the tonal scale of film and paper and uses the intensity of the light source to control his depiction of shadows. Then, he selects an appropriate background for his subjects from other photographs.

The accomplished illustrator Harvey Dunn commented, “The training Frank Reilly is giving his students is sound, and the artists among them will go far.” And “go far” Bama did—literally! In 1968, Bama was a successful New York illustrator at the pinnacle of his career when he and his wife Lynne traded the chaotic lifestyle of Manhattan for the solace of a small cabin on the Circle M Ranch on the South Fork of the Shoshone River, southwest of Cody, Wyoming. Bama moved 2,000 miles to become a realist painter.

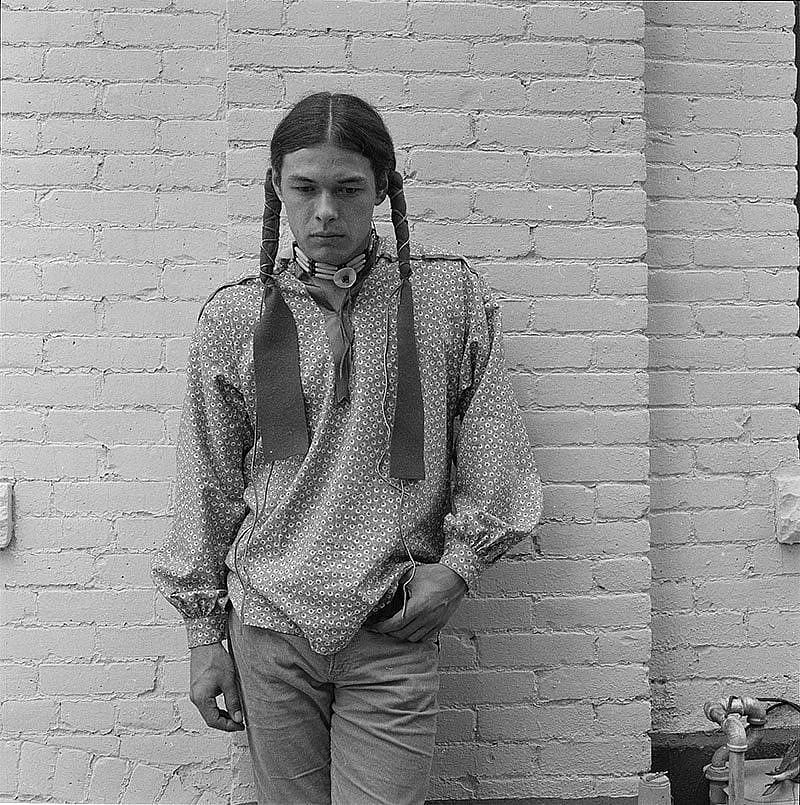

In 1974, Hollis Williford, a friend and fellow artist, invited Bama to a Native American basketball and soccer tournament in Denver. Knowing he would find interesting subjects for his portraits among the participants, Bama prepared a photography location in a small alley near the sports venue.

During the weekend, Bama experienced his most fruitful photography session to date. He found the young Indians he met at the tournament to be complex subjects worthy of his artistic efforts.

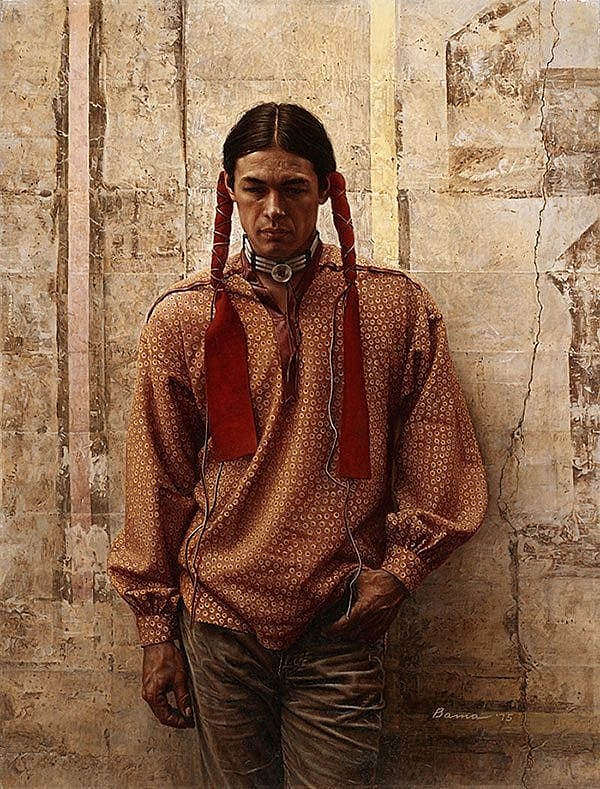

The 1975 oil-on-board titled A Young Oglala Sioux, depicts Rick Williams, the first Indian youth Bama painted. He effectively captured Williams’s personal attitude with a natural pose. The subject’s casual, yet reflective stance conveys not only his youthful vitality, but also his wariness. Williams’s attire suggests he is trapped between the contemporary world and cultural tradition. His ordinary rugged jeans bespeak working class values, while his braids, choker, and ribbon shirt represent his Indian heritage, noble values, and spirituality. A recent trend, ribbon shirts are commonly worn on reservations. Unwilling to take shortcuts, Bama worked painstakingly for weeks to recreate the shirt’s distinctive pattern.

Bama painted the young men he photographed in Denver against a contemporary backdrop, thereby avoiding stereotypical Indian motifs. “I was uninhibited by what other people had done with the traditional Indian,” he recalls. “I saw this as an opportunity to place them in a contemporary setting.”

In subsequent years, Bama painted a series of portraits of the young subjects he found in Denver. These works mark the pinnacle of his artistic development, and Bama feels they are his greatest and most successful artistic statement.

Bama’s integration of realism and abstraction set him apart from many of his realist peers and ultimately elevated his artistic prowess. He does not paint in the abstract expressionist sense of Jackson Pollack, but instead, he searches for abstraction as it appears in life.

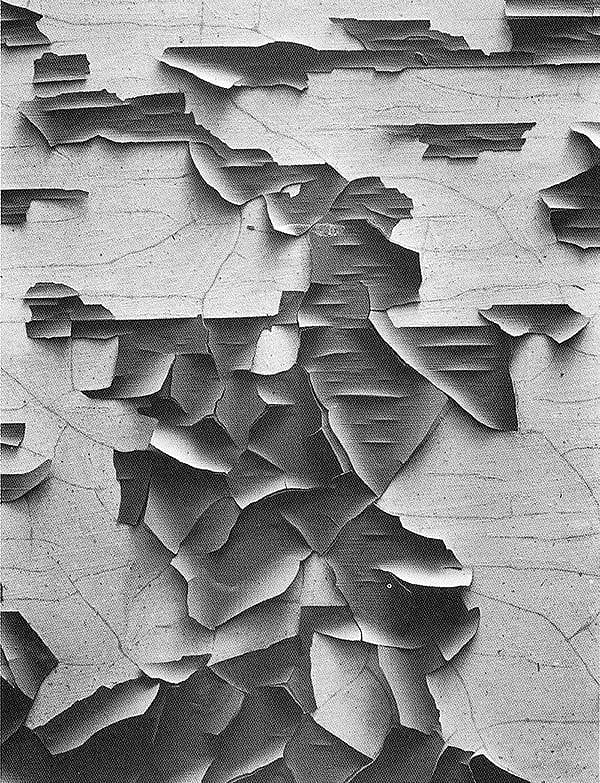

While traveling around Wyoming and Montana, Bama noticed the abstract beauty of old walls, which he began to photograph for future reference. Although he created an archive of such material for years, with no specific use in mind, he found the backdrops perfect for his portraits of contemporary Native Americans.

The abstract background used in A Young Oglala Sioux, for example, belonged to a building in Fromberg, Montana, an almost deserted town between Cody and Billings, Montana. This was Bama’s first significant integration of abstract art with realism. The harmonious confluence of the detail expressed in the subject, when contrasted with an abstract background, creates a complex painting.

Bama’s abstract backgrounds were inspired by Aaron Siskind, who often directed his camera at peeling walls. Siskind was a key member of the abstract expressionist movement in New York and its sole photographer. Twenty-three years Bama’s senior, Siskind shared more with the painter than an interest in photography: Both were native New Yorkers.

Siskind began his career as a documentary photographer in the New York Photo League in 1932. He photographed Harlem Document, an early essay of his work near where Bama lived and attended school.

In the early 1940s, after Siskind befriended abstract expressionists such as Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, and Mark Rothko, his work shifted to abstraction. Siskind exhibited his photographs at the Charles Egan Gallery, which specialized in abstract expressionism.

During the 1950s, Siskind’s primary subjects were urban façades, containing partial signs, graffiti, peeling posters, and isolated figures, and stone walls. His primary interests were in the flat, graphic messages they contained as he explored the problems of space, line, and planarity.

When photographing abstract façades, both Bama and Siskind deviated from mere documentation. As Siskind observed, “For the first time in my life, subject matter, as such, had ceased to be of primary importance. Instead, I found myself involved in the relationships of these objects, so much so, that these pictures turned out to be deeply moving and personal experiences.” For Bama, abstract façades provided a flat, contemporary background that contrasted with his three-dimensional human subjects.

Although Bama gravitated toward figurative realism early on, he never alienated himself from abstraction or other art movements or ideas. Bama often paints his subjects against non-specific present day backgrounds. As he once explained, “Rather than doing them with a teepee or a robe behind them, I thought I would put them in a completely abstract contemporary setting.”

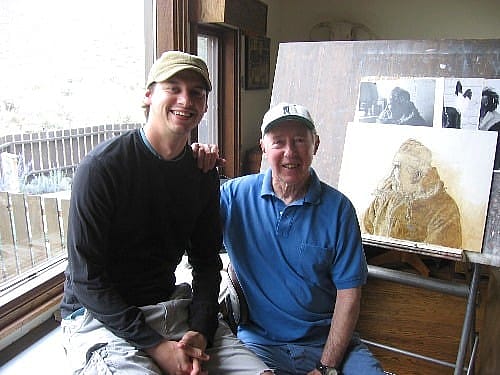

In 2003, Bama was the first recipient of the Buffalo Bill Art Show’s Honored Artist award and announced his plans to donate his archives to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. In summer 2005, the Center began working with him to prepare his archives for future inclusion into the permanent collection. Bama gifted his extensive photography collection in December 2006, and it is now at the Center’s McCracken Research Library for future generations to study and enjoy.

About the author

Thomas Brent Smith was appointed Director of the University of Oklahoma’s Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in 2021. Prior to that he held curator positions at the Denver Art Museum and the Tucson Museum of Art in Tucson, Arizona. In 2005, Smith worked as a Research Associate at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West to catalog James Bama’s studio collection. While a student at the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West, Smith received the Robert S. and Grace B. Kerr Foundation fellowship. His thesis, Native Americans in the Contemporary American West: the Portraits of James Bama, focused on the artist’s work.

Post 109

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.