Joseph Henry Sharp’s Monotypes – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West in Fall 1996

Joseph Henry Sharp’s Monotypes: On the Cutting Edge

Marie Watkins, Guest Author

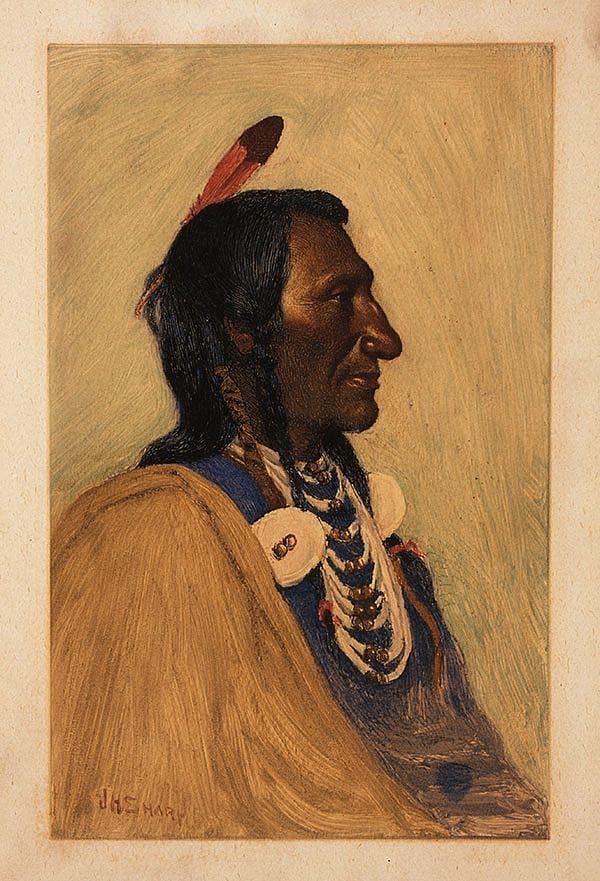

In the late nineteenth century American artists rediscovered the monotype process. Joseph Henry Sharp (1859 – 1953) of Cincinnati was on the cutting edge of this latest artistic development along with his eastern modernist colleagues. His accomplishments have been overlooked, however, in the current art historical literature on this art form.[1] Sharp contributed a distinctive subject matter with his monotypes of American Indians, such as Chief Red Cloud, Chief Two Moons, Spotted Elk, and two versions of Wolf Ear. The Whitney Western Art Museum collection includes these five portraits, as well as Sharp’s European landscape monotype, Afterglow. [2]

The monotype appeared as early as the seventeenth century in Italy and has been rediscovered or invented by artists in different times and regions. Although a print, the monotype is often thought of as a “painterly print,” positioned between the graphic arts and painting. To produce a monotype an artist usually paints with printer’s ink or thinned oil paints on a hard flat surface such as a sheet of glass, metal of wood. Paper is applied to the wet surface. The composition is transferred onto the paper through pressure from a press or by hand using such utensils as a spoon or washing machine wringer.

The perceived drawback of the medium is that it is an edition of one. The limitation is offset, however, by the spontaneity, direct energy and expressive nature of the work. The monotype displays rich and varied tonal effects from the layerings of ink and the wiping of the surface by fingers, rags, and sticks.

A member of the Cincinnati Art Club that actively experimented with the monotype, Sharp was cognizant of its artistic and commercial possibilities. Riding the crest of the monotype’s popularity, Sharp from 1897 – 1902 regularly exhibited his monotypes with art societies, museums and dealers in the East and West, introducing this art form to urban and rural areas removed from the cultural center of New York.

Newspaper reviews and exhibition catalogues hailed Sharp’s monotypes as the latest development in art and almost always included an explanation of the unfamiliar artistic process. Critics praised Sharp’s compositions for the artist’s unconventionality.

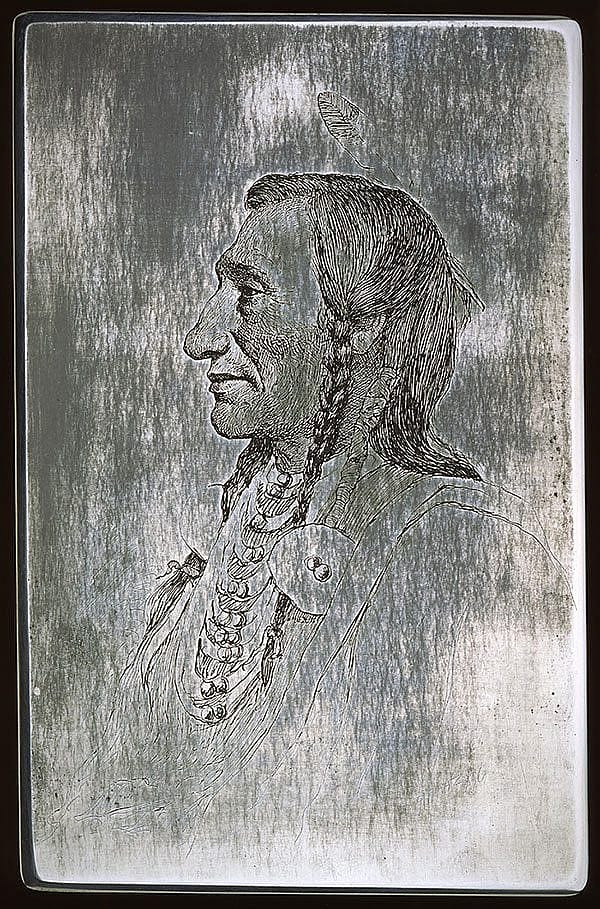

Techniques for making monotypes are as varied as their makers. Sharp appears to have developed independently the method of using etched plates to make some of his monotypes, although other artists used this method.

Emphasizing the serendipity of the process, Sharp wrote that he fooled his artist friends with monotypes in color over etched outlines. He said that from six feet away one could not tell the difference from an oil painting on canvas. Art critics particularly singled out his monotype portraits, stating they had the strength and force of oil paintings.

To produce this modified monotype Sharp first etched a design into a metal plate and then pulled an etching. Next he painted over the outlined image on the plate with colored paints. Placing the pulled etching over the painted plate, he matched the two images and again ran the pulled etching through a press.

The etched plate allowed Sharp to pull rapidly several monotypes, which would have variations. He could sell monotypes to the public at a reasonable cost of ten to twenty five dollars as opposed to two hundred dollars for an oil painting. For a fraction of the cost of an oil, a person of modest could purchase an original portrait of an American Indian, a subject that was in popular demand.

Monotypists often derive their imagery from their main artistic medium. Sharp was no exception. From 1893, Sharp devoted himself to painting what he and his contemporaries believed was the vanishing race of American Indians. He translated his first hand observation of Pueblo and Plains Indian life to the art of the monotype.

The immediacy and directness of the monotype suited Sharp’s working methods. The clean frozen profile of Wolf Ear exemplifies Sharp’s early style of Indian portraiture. The rich colors of the head executed in exacting detail stand in contrast to the sketchier and softer edges of the body. Although acclaimed for the ethnological value of representing types in his portraiture, Sharp captured the individuality of his subject. In a broader art historical framework, the subject matter of Sharp’s monotypes reflects a nation in transition, attracted to nostalgic American themes of a timeless past.

About the author

At the time she wrote this article for Points West, Marie Watkins was a candidate for a PhD in Art History at Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida. Her dissertation topic was “Poetics and Politics: The Patronage of Joseph Henry Sharp.” She studied in the Center’s Summer Institute in Western American Studies in 1994 and 1996, and did done research on Sharp in the McCracken Library, the Whitney collections, and the Joseph Henry Sharp cabin.

Notes:

1. See, for example, The Painterly Print: Monotypes from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980).

2. For the biography of Sharp and a discussion of his monotypes, see Forrest Fenn, The Beat of the Drum and the Whoop of the Dance: A Study of the Life and Work of Joseph Henry Sharp (Santa Fe, New Mexico: Fenn Publishing Company, 1983). For Sharp’s works at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, see Sarah E. Boehme, Absarokee Hut: The Joseph Henry Sharp Cabin (Cody, Wyoming: Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1992).

Post 111

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.