Chauncey McMillan and His Border Collies – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Summer 1999

Chauncey McMillan and His Border Collies

By Scott Hagel

Former Director of Communications

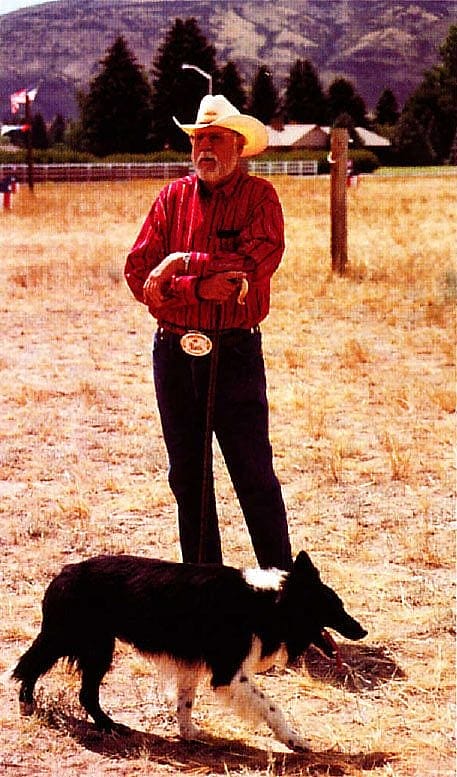

The crowd grows quiet and gazes into the distance. More than 100 yards away, a herd of angora goats mills restlessly. “Mikey, come by!” hollers the man in the cowboy hat. He follows the command with a distinctive whistle. A black shape bursts through the grass, circling the herd to the left, yet keeping his distance from the goats. The dog ends his first high-speed run by lying down abruptly, but his eyes never leave the herd. The animals begin to move slowly toward the man, away from the dog’s relentless stare.

In a short time, following a few more commands and whistles and highly choreographed sprints by the dog, the goats are penned. The spellbound audience bursts into applause. But it’s just another day handling livestock for Chauncey McMillan and his border collies.

Year in and year out, one of the favorite activities at the [former] Frontier Festival in Cody [was] the stock herding demonstration by Chauncey McMillan, his fellow dog handlers and the border collies he refers to as his “faithful friends.” Audiences are captivated by the communication and teamwork that allows Chauncey and his dogs to gather almost any kind of stock into pens or stock trailers. Most herd animals aren’t this easy to handle. Most dogs just don’t work like this.

But these are border collies, the Cadillac of stock dogs.

McMillan, a sheepman who lives east of Powell, Wyoming, never tires of showing what his dogs can do. “When I have to work my sheep, I can’t wait for the sun to come up. I know I’m going to have a wonderful time. And when something gets out, it’s no problem.”

But it wasn’t always this way. For years, he owned dogs of various breeds and attempted to use them with livestock. “I loved them, but they were useless,” he says. He had heelers that stampeded animals through fences and even a “Lassie-type” collie that would run away from the livestock. Then he became interested in border collies some 30 years ago. He got his first imported dog in 1977, and from that point on, there was no other breed for Chauncey McMillan.

Border collies are so named because they’re indigenous to the border areas between England and Scotland. It’s a breed that hasn’t been tampered with much over the past several hundred years. “They’re probably as pure a breed as there is going; they’re supposed to be one of the most intelligent dogs in the world,” explains Chauncey. They’re bred only for brains and working instinct. Conformation, size and color are of secondary importance. Conformation takes care of itself, Chauncey explained, because dogs that lack the correct physical attributes can’t do the work.

But despite his affinity for these animals, Chauncey had to learn to handle good dogs and train them properly. The key to successful training is to work with, rather than against, the dog’s natural instincts, he explains. For example, the dogs instinctively want to bring stock to the handler, rather than in some other direction. Therefore, training is more successful when the handler positions himself accordingly. “You set up situations that make it easy for the dog to do the right thing according to their natural instincts and hard to do the wrong thing…the dog will train itself.”

Training involves using subtle mental pressure—eye contact, a particular tone of voice—and the wise trainer immediately removes the pressure as soon as the dog does the right thing. “These are super-keen dogs,” Chauncey says. “You’re working with an individual that wants to please you.” Chauncey will not apply much pressure to a dog until he is at least a year old, because with younger dogs, their minds can’t keep up with their bodies.

The dogs are controlled with verbal commands and whistles, never with hand signals. The dogs control stock the same way their handler controls them, through pressure, which involves eye contact. “They’ve got this wonderful eye that’s been bred into them for hundreds of years and you don’t want to take that away from them,” Chauncey says. “So you never use hand signals.” With a dog keeping his eye on the stock at all times, they learn to listen for the appropriate cues. “Plus, when it gets dark, or it’s foggy or snowing, what good’s a hand signal?”

While other breeds are sometimes used for handling stock, none can match the well-trained border collie, and Chauncey makes this statement without any disrespect for other types of dogs. “At the big trials, you find nothing but border collies…. The other dogs just can’t compete. They’ve been bred for too many different things.

Chauncey’s dogs have won their share of prestigious competitions. His oldest dog, Nap, was High Point Open Dog of the Year in Wyoming in 1998 and has qualified for the national finals four times. His younger dog, Mikey, has also won his share of competitions.

Although Chauncey doesn’t take his dogs to overseas competitions because it would require them to be quarantined for six months—something he considers cruel for high performance working dogs—his proudest moment occurred the year before last when he saw the official program for the Supreme Championships in Ireland. An artist whom Chauncey had arranged to paint a portrait of Mikey had submitted the piece to officials associated with the trial.

There was Chauncey’s dog Mikey, featured in the program for the most prestigious stock dog trial in the world.

Post 114

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.