N.C. Wyeth – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2002

N.C. Wyeth: From the Hashknife to the Palette Knife

By Sarah E. Boehme

Former Curator, Whitney Western Art Museum

“Here I am in the great West,

and I’ll tell you it is the great West.”[1]

The twenty-one year old easterner, in search of adventure and knowledge, headed out to the Gill Ranch, east of Denver, Colorado, to join the fall round-up in October 1904. He had outfitted himself with saddle, bridle, boots, spurs, breeches, chaps, a slicker, and blankets. Unable to obtain his own horse, he hitched a ride with a sheepherder. Into the herder’s rig, the neophyte cowboy piled his newly purchased gear, as well as tools more familiar to him, but more unusual in this setting, his camera and sketchbox. At the sheep ranch, he persuaded the rancher to let him try a “bronc.” The rancher was saving his gentle horses, but with fairly low expectations of the easterner’s potential horsemanship, he allowed the young man to try an unseasoned mount. The horse pitched a bit, but the easterner hung on, earned the confidence of the westerners, and rode off to work on the round-up.

Thus the tenacious Newell Convers Wyeth demonstrated his mettle and the lengths he would go to gain authentic western experiences. Like other young men who came west, Wyeth sought to prove his strength and resilience against the hardships of a rough and wild life. Yet he had another purpose; he sought to understand the life of the West so that he could portray it honestly in paintings intended as illustrations for books and magazines. N.C. Wyeth had recently completed his studies at Howard Pyle’s illustrious school for illustrators. Even before traveling to the West, he had already gained some success as an illustrator of cowboy life, having sold a painting of a bucking horse and rider to the Saturday Evening Post for a cover. Following the advice of his mentor Pyle, Wyeth knew he needed to see the West himself, to gain the personal knowledge that would create the ideas for his art. Allen Tupper True, a fellow art student and a native of Denver, wrote to his mother in Colorado about Wyeth’s impending visit and asked for her help in finding Wyeth a place where he could see the “puncher life.” True concluded, “Wyeth…is the kind of fellow one wants to help—self-made and reliant.”[2]

For two weeks Wyeth rode for the Hashknife Ranch, participating in all the cowpunchers’ labor and relishing in the outdoor life. He had originally intended only to observe and sketch the round-up from the vantage point of the grub-wagon, but instead he found himself rising from his outdoors’ bed-blankets at day break and then roping, riding and cutting-out until sundown. The New England bred art student had companions called Dutch Lou, Scotty, and the Swede. The costs of maintaining the necessary string of horses consumed his monetary wages of eight dollars a week, but he earned priceless experience. He got thrown off his steed, suffered a broken foot from a horse misstep, accepted the cowboys’ initiation rite of being thrashed with chaps, and faced death’s nearness when the camp gathered around a young rider’s lifeless body. He recorded in his diary, “A boys body brought in by two horsemen rolled up in a yellow slicker. The bad omens of the previous night proved only too true. The horse had thrown the boy and had kicked his head to pieces.”[3] Wyeth had little time for color sketches and seems to have forgotten to bring a crucial paint, so instead he made some pencil sketches in the evening, took some photographs, but more importantly he literally soaked up experiences that would be kinesthetically remembered when he faced an easel with paints, brush and palette knife.

He hurried back to Denver, Colorado, rented a room to use as a studio, and wrote exuberantly to his mother, “I have spent the wildest, and most strenuous three weeks in my life. Everything happened that could happen, plenty to satisfy the most imaginative. The ‘horse-pitching’ and ‘bucking’ was bounteous.”[4] He transformed his experiences into four paintings whose subjects were roping horses in a corral, a bucking horse in camp, driving cattle through a gulch, and a scene around the grub wagon. After additional experiences visiting southwestern Indians, Wyeth headed back east to resume his career as an artist-illustrator, reaching Wilmington, Delaware, before the end of the year 1904.

Wyeth showed his cache of four round-up paintings to Pyle, who liked two of the works, but was concerned that the others resembled too much the art of Frederic Remington. Wyeth had received financial support from Scribner’s Magazine to make his western journey and he now needed to prepare images for their publication. He had painted his four works in a horizontal format, probably influenced by the insistent horizontality of the western landscape he experienced. From a Colorado ranch, he had described the view, “Out of the west window, plains; out of the east, plains; out of the north window, plains; out of the south, plains.”[5] Scribner’s, however, featured a vertical format, so he produced another seven paintings, suitable for the magazine, and wrote a narrative around them, “A Day with the Round-up: An Impression.”

The paintings and the text trace an imaginary day beginning with gathering for the early morning meal, and encompassing the dusty work of roping an unwilling horse, subduing an untamed mount, rounding up the stray cattle, racing with abandon for the noon meal, separating the cattle with different brands from the gathered herds, and concluding with the evening setting as the night wrangler takes over the duties of watching the herd. In their vertical format, Wyeth’s paintings orient themselves around the human figure rather than the landscape. The natural environment is indicated in the dust enveloping the horse corral and the sharp angles of the canyon where the cattle had to be gathered, but it is the human action that concerns Wyeth.

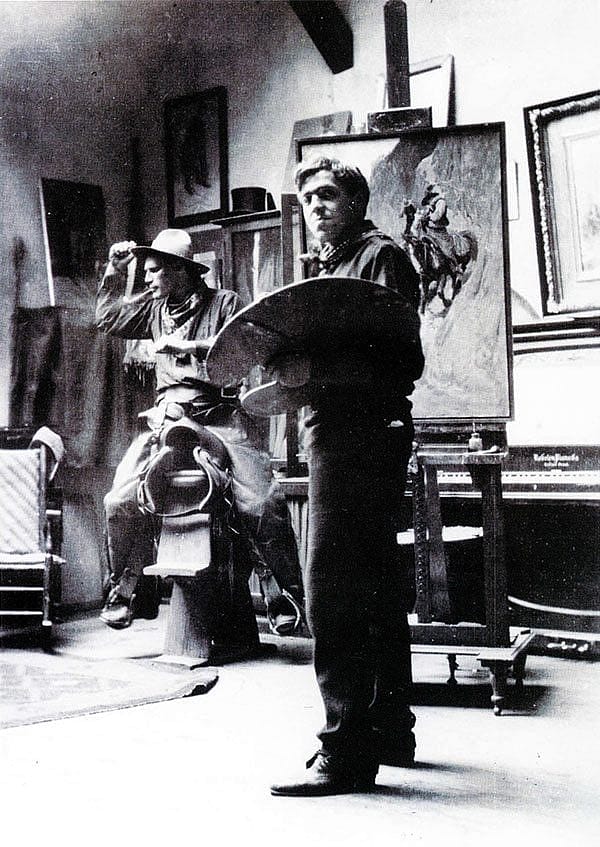

In Above the Sea of Round, Shiny Backs the Thin Loops Swirled and Shot into Volumes of Dust, the crouching roper balances his weight on one leg and reaches across his body with his roping arm, poised to throw his loop at just the right moment. The cowboys gallop directly toward the viewer, urging their horses with hats, quirts and ropes in The Wild, Spectacular Race for Dinner. Sharply foreshortened, the lead horse seems to burst through the imaginary picture plane into the viewer’s space. Back in his studio Wyeth used the gear he had purchased as props. He posed fellow artist Allen True, whose parents had offered western hospitality to Wyeth, to capture the cowboy contrapposto of the herder in the painting Rounding Up. Although Wyeth completed these paintings in his eastern studio in 1905, he dated all the paintings from the series 1904, probably to emphasize the year of their genesis in experience.[6]

“A Day with the Round-up” appeared in the March 1906 issue of Scribner’s Magazine [read Wyeth’s article with the illustrations in our 11.08.2015 post], published with four paintings reproduced in color and the other three in black and white. This attention to the young artist helped to further Wyeth’s career as an illustrator, especially of western images. This first great success demonstrates the power of Wyeth as a narrative painter of action and emotion. Although the seven paintings (six of which are owned by the Buffalo Bill Center of the West) would be used and reused to illustrate various texts, they themselves were created as primary visual images. Wyeth wrote the text after having conceived the basic ideas for the images. The text elucidated, but did not overtake, the visual narrative. Throughout his career, Wyeth demonstrated his ability to convey dramatic meaning in his paintings, no matter what the source of the subject might be or whether he was illustrating a pre-existing text.

Wyeth, who was born in Needham, Massachusetts in 1882, had studied in New England before being accepted in Howard Pyle’s school in Delaware. While studying in Wilmington, he met Carolyn Bockius, whom he married in 1906 between western journeys. He made a second trip to Colorado early in 1906 and planned a third trip to the West later that year, but only went as far as Chicago and Kansas City. He bought land in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania where he painted and illustrated until his death in 1945. Although he never traveled to the West again, he did continue to illustrate Western subjects, including the life of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. His son Andrew, daughter Henriette and grandson Jamie continued the Wyeth artistic legacy.

Notes:

1. N.C. Wyeth to Henriette Zirngiebel Wyeth, Denver, Colorado, September 29, 1904, as quoted in Betsy James, ed., The Wyeths: The Letters of N.C. Wyeth, 1901 – 1945, Boston, Gambit, 1971, p. 100.

2. Allen Tupper True to Margaret Tupper True. September 5, 1904. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

3. N.C. Wyeth, as quoted in, Brandywine River Museum, N.C. Wyeth’s Wild West, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, 1990. p. 66.

4. N.C. Wyeth to Henriette Zirngiebel Wyeth, Denver, Colorado, October 19, 1904, The Wyeths, p. 106.

5. N.C. Wyeth to Henriette Zirngiebel Wyeth, Limon, Colorado, The Wyeths, p. 99.

6. Dating first explained by James H. Duff in memo to Buffalo Bill Historical Center, December 26, 1979. See The Western World of N.C. Wyeth, text by James H. Duff, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 1979. For more information on Wyeth, see also Douglas Allen and Douglas Allen, Jr., N.C. Wyeth: The Collected Paintings, Illustrations and Murals, New York, Bonanza Books, 1972, and David Michaelis, N.C. Wyeth: A Biography, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

Post 115

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.