A Day with the Round-up: An Impression by N.C. Wyeth – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2002

A Day with the Round-up: An Impression by N.C. Wyeth

By N.C. Wyeth

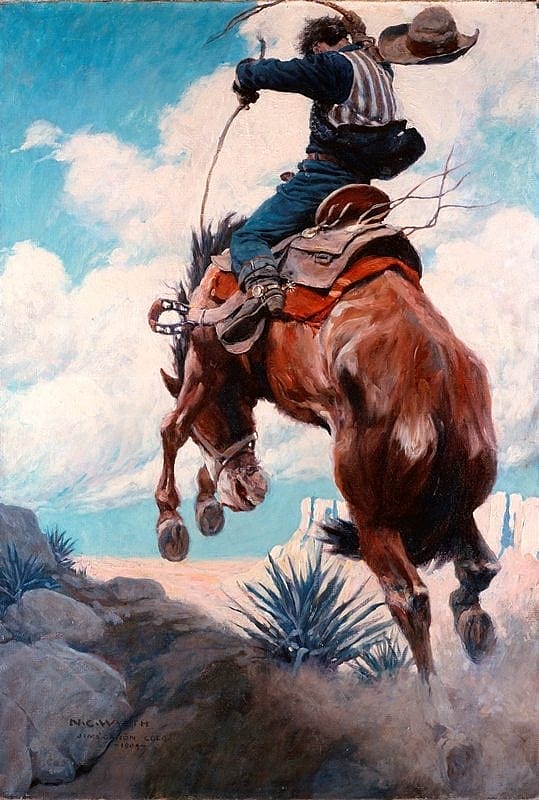

Ed. note: Artist Wyeth wrote this story for the March 1906 issue of Scribner’s Magazine (Vol. XXXIX, no. 3), pages 285 – 290. The paintings accompanying it appeared as illustrations with that article.

Groping and feeling my way out from beneath three or four thick blankets and turning back to the stiff dewy tarpaulin, I peered into the gloom of early morning. The sweeping breeze of the plains brushed cool and fresh against my face. Shapeless forms of still sleeping men loomed black against the low horizon. Near by I saw silhouetted form of the cook’s thick legs and a big kettle swing before the light of the breakfast fire. I stared in wonderment about me—then my confused mind cleared and I remembered that us was the cow-camp of the night before.

I hurriedly pulled on my boots and rolled the great pile of still warm blankets into a huge bundle and tied them so with two shiny black straps. Dark figures were moving about the camp—some crawling from beneath heaps of tangled beds, others trundling their big ungainly rolls, lifted high on their backs, to the bed-wagon. And so I carried mine, joining the silent processions that moved, a vague, broken line in the growing light of the early morning.

Suddenly into this strangely quiet fragment of wild life, the cook’s metallic voice pierced the silence like a thing of steel.

“Grub’s ready. Hike, yer bow-legged snipes er the valley; I cain’t wait all day; what ter hell d’ye think—I come frum Missoura?”

Then I joined the dark mass of men around a tin pail of water. The cow-punchers do not wash very much on the round-up. A slap of water to freshen the face, a vigorous wipe with a rough, wearisome towel, and the men were ready for their breakfast.

I joined them—a crowd seated in the lee of the grub-wagon. Everything was very quiet, save now and then the click of the spoons on the tin cups. They ate in silence, all unconscious of the rich yellow glow that was flooding the camp.

Then the quiet of the morning was broken by a soft rumbling that suddenly grew into a roar, and from a great floating cloud of golden dust the horse herd swung into the rope corral.

The men tossed the tin cups and plates in a heap near the big dish-pan. There was a scuffle for ropes and the work started with a rush. In the corral the horses surged from one side to the other, crowding and crushing within the small rope circle. Above the sea of round, shiny backs, the thin loops swirled and shot into volumes of dust; the men wound in and out of the restless mass, their keen eyes always following the chosen mounts. Then one by one they emerged from the dust, trailing very dejected horses. The whistling of ropes ceased, and with a swoop the horse herd burst from the corral to feed and rest under the watchful eye of the “wrangler.”

By now we had all “saddled up” and mounted save “The Swede.” He was very short, with a long body and bowed legs; his hair and eyebrows light against the burned red of the face. His belt hung very low on the hips, and his blue jeans were turned up nearly to the knee. The ribbon of his high-crowned felt hat was bordered by the red ends of many matches and he wore a new white silk handkerchief that hung like a bib over his checkered shirt.

We watched him as he led his mount into “open country,” for the horse was known to be “bad.” His name was “Billy Hell,” and he looked every bit of that. He was white, of poor breed, and probably from the North.

“The Swede” walked over to the nigh side of his horse and hung the stirrup for a quick mount. Then he ran his hands over all the parts of the saddle, giving the cloth a tug to see if it were well set. He pulled up the latigo one or two more holes for luck and spit into his rough hands. The horse stood perfectly still, his hind legs drawn well under him; his head hung lower and lower, the ears were flattened back on his neck, and his tail was drawn down between his legs. “The Swede” tightened his belt, pulled his hat well down on his head, seized the cheek-strap of the bridle with one hand, and then carefully fitted his right over the shiny metal horn. For an instant he hesitated, and then, with a glance at the horse’s head, he thrust his boot into the iron stirrup and swung himself with a mighty effort into the saddle.

The horse quivered and his eyes became glaring white spots. His huge muscles gathered and knotted themselves in angry response to the insult. Then with his great brutish strength he shot from the ground, bawling and squealing in a frantic struggle to free himself of the human burden. It was like unto death. Eight times he pounded the hard ground, twisting and weaving and bucking in circles. The man was a part of the ponderous creaking saddle; his body responded to every movement of the horse, and as he swayed back and forth he cursed the horse again and again in his own native tongue.

Then it was over. The cow-punchers nodded in approval and one of them dropped from his saddle and picked up “The Swede’s” hat.

“Rounding-up” means to hunt and to bring together thousands of cattle scattered over a large part of the country known as the free range. For convenience in hunting them, the free range is divided into a number of imaginary sections. Into these sections the “boss” of an outfit sends the score or more of punchers, divided into squads of twos and threes, each squad covering a given section. This is called “riding the circle.”

The boss of our outfit was a man by name “Dale” Middlemist—the cow-punchers call him “Date.” He was of a silent nature, of keen perception, and without an equal in his ability to locate the wandering herds of cattle.

After a day’s round-up he would talk to his men of the work and tell them what section they were to cover on the morrow, and once I remember he came to me and asked how I had fared for the day—and if I were saddle sore. I told him “No!”

“Then,” he said, you can work with Scotty Robinson and Crannon to-morrow. You’ll ride the ‘Little Cottonwood Crik’ country.”

And as he was leaving he turned and added, “It’s a ____ long ride.”

And so in the morning I started out with the others on the trail of some four or five hundred cattle.

We rode many miles, finding every little while a few of the cattle, some three of four, perhaps, standing quietly together in a gully. And as we pushed our way toward the distant camp of the outfit that had moved to the farther end of the section since we left, our herd gradually increased. With the added numbers the driving became difficult and we had to crowd our horses into the rear of the sullen and obstinate herd. We crossed, recrossed, and crossed again, yelling and cursing and cutting them with our quirts. The herd slowly surged ahead, above them floating a huge dense cloud of silvery dust that seemed to burn under the scorching sun of the plains.

It was well-nigh to noon before we saw a sharp line on the horizon that appeared and disappeared as we rose and fell along the undulating creek bottom. We knew the dark line to be the cattle already rounded up, and that we were late. But we had ridden the big circle that morning.

Our cattle soon saw the larger herd, and their heads went up, their tails stiffened, and they hurried to join the long dark line that began slowly to separate itself; as we drew nearer, into thousands of cattle. And as we approached the main herd our cattle became more quiet. From the distant waiting multitude, as if in greeting, came a low, rumbling moan. The sound was faint; it became audible as the hot wind of the plains blew against my face, then it died away again—even as the wind spent itself on the long stretch of level plain.

Soon our cattle were on the run, and from a distance we stopped and watched the two herds merge one into the other. We were late, and the cow-punchers greeted us with jibes of all sorts, but we did not mind them, for the day’s drive was over. To the right of the herd, some six hundred yards, stood the grub-wagon. Near by it I saw the smoke slowly rising from the cook’s fire, and my appetite was made ravenous. Someone called, “Who says dinner?” and with that came the stinging crack of many quirts, the waving of hats, the whirling of ropes, and with the cow-boys’ yells—that I believe have no equal,—there followed a wild, spectacular race for dinner.

My horse was tired and streaked with sweat and white dust, his ears drooped, his tail hung limp, and he breathed hard, but I found myself in the first “bunch” at the finish. I jumped to the ground and hurriedly loosened the saddle and the soaking wet blanket from the horse’s back and threw them onto the hot ground to dry. Then I made for the soap-box of tin dishes and heaped my tin plate with meat and potatoes, and afterwards, by way of dessert, I had a small can of tomatoes. We sat in the shade of the grub-wagon, and along with the eating then men told of a large herd of antelope they had seen and of an unbranded cow they had brought in.

The “wrangler” ended the dinner. Into the camp he drove the horse herd, and from it fresh mounts were roped for the afternoon’s work of “cutting out.”

Cutting out is a hard, wearisome task. There were some six thousand cattle in the herd that had been rounded up that morning, and it was the work of the men to weave through that mass and to drive out certain brands known as the “Hash Knife,” the “Pot Hook,” the “Lazy L,” and the like.

The herd that had been quiet was again in a turmoil, bellowing and milling, but it was kept within limited bounds and well “bunched” by the score or more of punchers outside.

My roan was well trained. He seemed to know by my guiding which cow I was after, and kicks and bites, we would separate our cow from the writhing mass. I could faintly see my fellow-workers, flat silhouettes in the thickening dust, dodging and turning through the angry mass of heads and horns. My throat grew parched and dry, and the skin on my face became tight and stiffened by the settling dust. Once I stopped to tie my silk handkerchief over my mouth; I found it a great help.

And so the afternoon passed quickly. I rode for the last time into the sullen herd, carefully watching for any remaining cows with the brand of the “Hash Knife.” But I did not find any; my work was finished and I rested in the saddle, watching the remaining men complete their “cutting out,” helping them now and then with a stray cow.

The sun was low and very red, the shadows were long and thin. The afternoon’s work was completed, and I was glad. From across the plain I saw the red dust of a small herd that had already left camp on their long night journey to the home pasture, and I heard the faint yelps of the cow-boys who were driving them. I dismounted and with the knotted reins thrown over my arm, slowly walked back to the grub-wagon.

Some of the beds had already been unrolled, and I spread mine in a good level place. The ground was still hot and dry, but the air was rapidly becoming cooler, and the dew would soon fall.

In twos and threes the men came into camp, tired and dusty. We grouped about the wagons sitting on the tongues, on unrolled beds, anywhere, perfectly contented, watching the cook prepare the evening meal. The odor of coffee scented the air, and I was hungry and tired as I never was before.

After the supper, a circle of men gathered about the camp-fire. The pulsing glow of many cigarettes spotted the darkness; the conversation slowly died with the fire, and one by one the dark, somber faces disappeared from the light.

I was the last to leave. I crawled into my blankets and lay for a moment looking into the heavens and at the myriads of stars. I pulled the blankets up to my chin and then I felt the warmth of the ground creep though them. As I lay there I heard the faint singing of a night herder floating across the plains, and—for an instant—I thought of the morrow.

Post 116

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.