Tourism in Yellowstone – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 1998

Tourism in Yellowstone

By Lawrence Culver

Former Intern, McCracken Research Library, 1997

The creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 has been viewed as a turning point in American history, the beginning of a new relationship between Americans and their environment. However, the Park’s creation was also a defining moment in the history of the West, as the region transformed from a frontier for exploration and settlement into a frontier for recreation. Yellowstone did more than preserve nature; it transformed scenery into a tourist attraction.

At first, the Park attracted the affluent, people who could afford adventuring in the western wilderness.

Although some visited the Park in wagons or on horseback, most early tourists arrived by train. Railroads, not surprisingly, had avidly supported the Park’s creation. Train travelers entered Yellowstone from the north, arriving at Gardiner, Montana. They proceeded through the Park in coach tours. However, accommodations were poor, costs high, and food often tainted.

Even coach holdups were not uncommon. Moreover, while criminals robbed tourists, poachers killed wildlife and visitors vandalized natural formations. The Army was ultimately placed in charge of the Park, which had been created without any funding or agency to operate it.

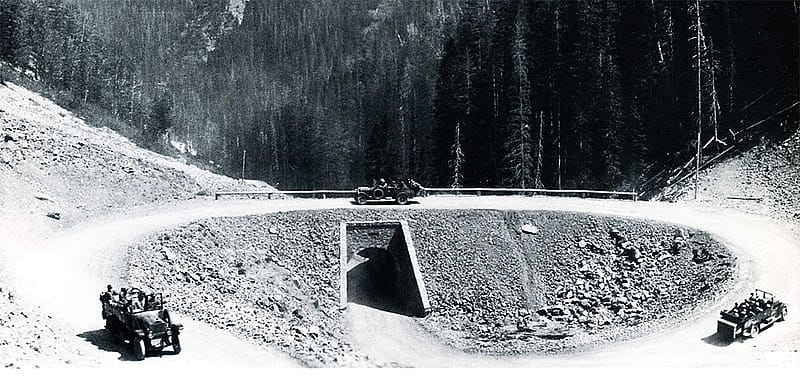

With the invention of the automobile, tourists finally had an alternative way to travel. Succumbing to widespread pressure, the Department of the Interior rather reluctantly allowed the first cars into Yellowstone in the summer of 1915. In 1916, however, the newly-created National Park Service began aggressively courting auto-tourists. Though some dismissed them as “tin can tourists,” Yellowstone embraced them. In an era when national parks were little-visited and sporadically funded, increased visitation seemed the perfect way to attain solvency. Tourists could travel on their own, camping where they wished. Now thousands of middle-class citizens could aspire to visit America’s first national park.

More importantly for the greater Yellowstone region, most tourists no longer had to enter the Park from the north at Gardiner. They could enter from other gateway communities: West Yellowstone, Cooke City, Jackson and Cody. These towns began to jockey for position, clamoring for road construction funds and each claiming the best route to Yellowstone.

For Cody, founded in 1896, tourism promotion was nothing new. Linked to the fame of Buffalo Bill Cody and provided with rail access through Cody’s personal lobbying efforts, townspeople quickly learned the value of supplementing their agricultural income with tourist dollars.

Buffalo Bill had suggested a new eastern route to Yellowstone before Cody’s founding, and a wagon road following this route was cleared by 1903. Wapiti Inn and Pahaska Tepee, Buffalo Bill’s resorts, opened in 1904 to take advantage of the new traffic. When the Park opened to automobiles, Buffalo Bill himself led a caravan from Cody towards the East Entrance.

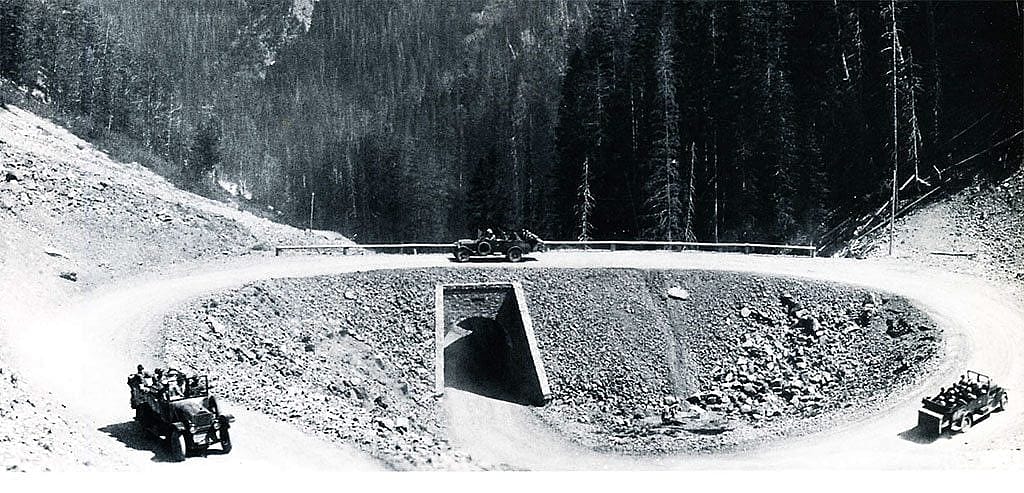

Townspeople eagerly promoted the route, but some tourists found the road, with its steep inclines and precipitous cliffs, a bit too scenic. Motorist Melville F. Ferguson, an author who traversed it in the 1920s, was warned that the road “wound for miles along the very brink of a precipice two thousand feet high, with a rock wall on one side and eternity on the other.”

Such dire descriptions led park and state officials to modify and reconstruct the highway in a series of construction projects that continue today. Despite the purported dangers, travel through the East Entrance burgeoned. By 1920, autocamps opened in Cody, providing accommodations for motorists. Traffic increased exponentially after World War II. The town of Cody also grew, as new motels, gas stations, and shops were built. The Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] likewise expanded rapidly, benefiting from its proximity to Yellowstone.

The mass visitation remade Yellowstone’s gateway towns, transforming them into tourist destinations themselves, their citizens promoting images of the “Wild West” even as that older world proved ever more distant from their bustling, trendy present. The towns are changing even more rapidly today, as disaffected urbanites relocate to the Rocky Mountain West. In Yellowstone, cars are no longer a blessing but a burden, causing congestion and degrading the wilderness experience that tourists seek.

As we celebrate the 125th anniversary of Yellowstone and consider its place in 21st century America, we would do well to remember that national parks cannot simply preserve pristine places. They inevitably change them.

Post 119

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.