Old West, New West: Conservation Paradigms – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2004

Old West, New West: Conservation Paradigms

By Mark Bagne

Guest Author

Knight and Charles R. Preston, PhD, curator of the Draper Natural History Museum, are among those at the forefront of an effort to construct a new paradigm of conservation that incorporates humans as part of the environment while adapting to monumental changes that are shaking the West to its core. They led a June 2004 session of the Center’s Larom Summer Institute in Western American Studies called The Old West, the New West, the Next West: Myths and Realities.

“For one reason or another, all of us are in love with this region, even if we live outside of it, and we are all trying to figure it out,” Knight says. “But we are focused on the rear-view mirror, and we’re not looking through the windshield. This is the time we need to be focusing on the road ahead because we are on the cusp of momentous change. Everything in the American West is changing—the demographics, the economics, the land uses, the biodiversity. All of those things are in a state of play we really haven’t seen since the 1800s. These are not ordinary times.”

As viewed through a camera positioned on a satellite, a snapshot of America at night shows clusters of human-made lights that wouldn’t have even registered twenty years ago. It’s dramatic evidence of what Knight calls the greatest redistribution of the American population since the homestead days. While maps dating to the 1950s show four-fifths of the West dedicated to range livestock, contemporary maps depict the region as America’s playground—dotted with icons indicating zones for four-wheeling, whitewater rafting, skiing, and golfing. This rapid influx of new people and new interests has stirred a “cultural upheaval” as dramatic as the upheaval Preston experienced while growing up in the South in the 1950s and ’60s. Faced with these changes, westerners hold onto myths and treasured values and blame “outsiders” for many modern dilemmas.

I have never been in a region where I’ve seen so much dogma,” Knight says. “The hardest thing in the world, because of the depth of the mythology, is to have an informed conversation on human and natural histories in the American West.”

From the perspective of many rural westerners, demands to protect endangered species or transfer water rights to urban areas challenge strong traditions of independence, private property rights, and even the ability to make a living. Rural people produce valuable commodities and protect open space and wildlife habitat without adequate reimbursement or even appreciation. “People in urban areas don’t seem to care as long as they get the best cut of steak at the lowest possible price,” Knight says.

Contemporary attitudes toward wolf restoration stem to the early 1900s. After native ungulates were nearly exterminated by unregulated human exploitation, wolves took huge tolls on cattle and sheep and the nation at large rallied behind efforts to exterminate the predators. Preston notes the grandparents of many modern ranchers led that campaign, and they were considered heroes. Now the rancher who finds dead livestock in his field must document confirmation of a wolf-kill to receive compensation. That can be impossible if all he finds are scattered bones. “A wildlife biologist can tell a rancher all day long that livestock predation by wolves is less than predicted, but if you’re the guy who just lost fifteen sheep, that doesn’t mean much to you,” Preston says. “We have Old West cultural values and perceptions, and we have a New West issue in this restoration of endangered species, and boy, are they butting heads.”

Knight says the West appears to be in conflict not only within its region but also with the entire United States, considering that the United States has ownership in the full half of the West that falls in the public domain. Ever since the “unregulated exploitation” of the West of the 1800s, Americans have exercised various strategies designed to protect its resources. Arising from the Teddy Roosevelt administration, these strategies eventually spawned preservationists, conservationists, and environmentalists.

the late 1960s, while working for the Washington Department of Game, Knight participated in a style of preservation he ironically refers to as “the gospel of efficiency.” Under this mandate, civil servants wielded power without regard for the “social dimensions” of their actions. “We went where we pleased and got what we wanted,” Knight recalls. “We would intimidate and put the fear of God into a landowner. I remember the days when I didn’t even ask a landowner if I could climb up to a golden eagle nest. Somebody should have told me, “You can’t talk to these private landowners this way.” This bureaucratic and legalistic approach bred mistrust and resentment.

“The Endangered Species Act was nice when it was trying to save the bald eagle or the Florida alligator,” Knight says. “But when it tries to save the Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse, all of a sudden it becomes onerous. And when it tells ranchers they can’t spray Canada thistle, and they can’t irrigate, and they can’t graze cows seasonally in riparian areas, it becomes a pain in the butt.”

The 1990s ushered in a new model for conservation that promotes stewardship across administrative boundaries. “Ecosystem management says that if you work for the Forest Service, you’d better stop at that fence, extend your hand over to the private landowner, and introduce yourself to your neighbor,” Knight says, “because you will never deal with fire issues and weed issues and land issues or any issue, political, economic, or ecological, if you do not have relationships on all sides of the boundaries. You can’t manage natural resources with computer spreadsheets. You have to work with people.”

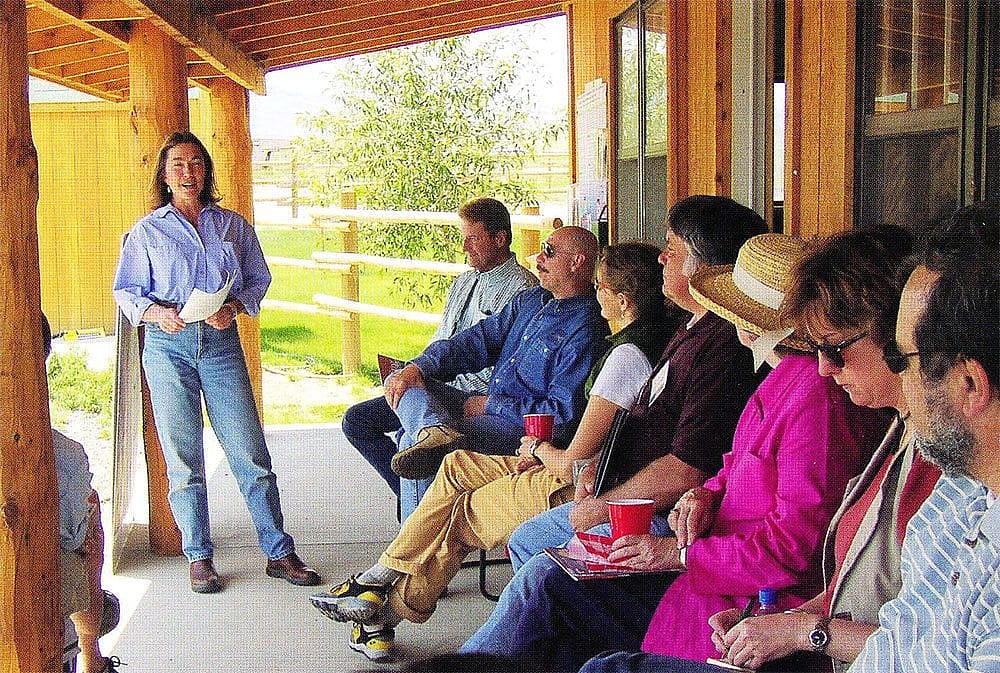

In contrast to command-and-control techniques that enforce technological solutions even in the face of evidence showing they aren’t working, ecosystem management promotes adaptive strategies based on test studies from the field. Ultimately, ecosystem management places the health of the land first and foremost—to the benefit of the humans who inhabit and cultivate the land. As part of their session at the Larom Summer Institute, visiting scholars from as far as Massachusetts saw a grassroots conservation effort in action at the Hear Mountain Ranch—owned and operated by The Nature Conservancy near Cody. The community grassbank at this ranch provides livestock forage at affordable rates for ranchers allowing them to rest grazing allotments and/or conduct ecological restoration. The class also visited lands and projects administered by the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, and private landowners to gain a broad perspective regarding issues of land use management.

Everything that’s good comes to us from healthy landscapes,” Knight says. “Nothing but problems come from degraded and unhealthy landscapes. We need to get to this point where we put the health of the land first; knowing the long-term health of human communities is entwined with the health of the land. No community is healthy if it can’t produce food, potable water, and breathable air.”

Knight and Preston say the conservation paradigm of the twenty-first century will be community-based—with a driving goal of finding common ground and building bridges across the gap between rural and urban communities. Instead of segmenting ecological, economic, and cultural concerns, it will integrate them.

“What we see right now is an all-or-nothing paradigm that still rules some parts of the West.” Preston says, “If a person holds one view, we snap this colored jersey on him and say he can’t take part in the discussion. We have to take those jerseys off and become people again, so everyone can have a voice. We have to build trust where there’s no trust now and work to replace dogma with information.”

Far from representing a fantastic vision for the future, Knight observes that community-based conservation is currently thriving among hundreds, and probably thousands, of locally driven collaborative efforts that might loosely fall under the umbrella of an initiative called the Radical Center. Knight was one of a small group of citizens who formed the Radical Center to include so-called radicals and liberals on the right and so-called conservatives and reactionaries on the left. “The seven of us who came together two years ago were all tired of fighting,” Knight recalls. “When you’re young you like to fight, but when you get older you realize, well, what good did fighting do? All of us, from different walks of life and experiences, were just tired of fighting.”

“The only thing that’s going to save the natural heritage of our region—the thing we love so much—is people,” Knight says. “The only was the hysterical voices of the far right and far left will be dimmed is by people, gradually over time, abandoning those choruses and making a new chorus.”

Post 120

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.