Before There Was Molesworth High Style There Was Cowboy Low Style – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 1998

Before There Was Molesworth High Style There Was Cowboy Low Style

By Joanita Monteith, Guest Author

From the summit of Cedar Mountain, Buffalo Bill Reservoir shines like a sheet of hammered silver to the west and the town of Cody reveals itself to the east. This was and is the domain of William F. Cody, world famous for his Wild West Show, which helped to create the romantic myth of the cowboy and the West that persists even today.

It was upon this myth that Thomas Molesworth capitalized. He was the legendary designer and craftsman who popularized world-class western furnishings from about 1933 to 1961 from his shop in Cody.

If Molesworth’s chic western decor is called Cowboy High Style as a tribute to its design excellence, what then do we call the traditional, homemade plank and pole furniture that inspired and predated it? Some might call it Cowboy Low Style, but the only thing this forerunner was low on was design sophistication. It was meant to be functional and much of it was built out of necessity, on the spur of the moment, by builders who most often had no experience at crafting fine furniture.

This Cowboy Low Style furniture was first made by area homesteaders in the late 1800s. Around the turn of the century, it was adopted by area dude ranchers as a quick and economical way to furnish their ranches. It was ideal because it could be built by ranch hands, who might build fence, tend horses or lay up fieldstone fireplaces one day and build rustic furniture the next.

Best of all, guests delighted in the style. It had precisely the looks they wanted and expected as part of a western dude ranch vacation.

Thomas Molesworth had other inspirations for his designs besides the western myth and the example of Wyoming’s historic homemade furniture. He was well traveled, and he had trained at the Chicago Art Institute in 1908-09, where he was exposed to Adirondack Eastern Lodge style and to the most sophisticated designs of the era, such as Art Deco and the Mission style of the Arts and Crafts movement, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright. Function may have dominated early homestead furniture, but not so for Molesworth. He was a stickler for quality materials, workmanship, design and function.

Some of the classic, original Molesworth pieces have the look that the uninitiated would expect to find in a place like Roy Rogers’s living room. The styles were as classy as Roy’s Hollywood costumes. Of course, real cowboys were not outfitted like that, and neither were their living rooms. But no one cares. It’s all part of the American love affair with the West. Some of the best parts have been largely imaginary.

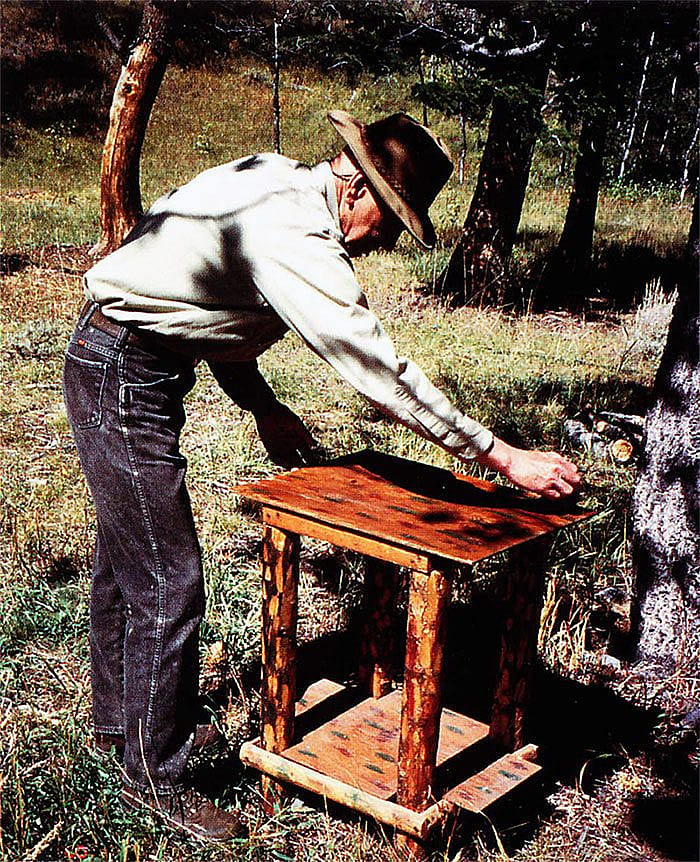

While few would deny that Molesworth was king of the road in western furniture during his years of operation and that today his legacy influences craftsmen far and wide, others had a role to play. One of those was Carl Dunrud. He built the buildings and furniture for the Double Dee Dude Ranch in northwest Wyoming in 1931, the same year Molesworth set up shop in Cody. Little did Dunrud and his ranch hands know that in building the old style furniture for the ranch, they were providing for future generations a unique glimpse into the grassroots traditions that underpinned Molesworth’s vision. They had more practical concerns in the hard times of the Great Depression.

Dunrud first got the idea to build a dude ranch after participating in an expedition to Greenland with his friend George Putnam. The best-known publisher of his day, Putnam was the husband of aviator Amelia Earhart. The purpose of the Greenland trip was to capture a live polar bear for exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Dunrud was a Yellowstone National Park ranger, and the two first met when Putnam and a group of scientists were studying Yellowstone’s Geyser Basin. When Dunrud decided to build his dude ranch, the wealthy and influential members of the Yellowstone and Greenland expeditions offered to be paying guests and to help promote the ranch.

The ranch buildings were made of logs. Born and raised in Minnesota, Dunrud was familiar with this style of building in the tradition of his Norwegian ancestors. The buildings show the same attention to craftsmanship as the furniture that would fill them. Doug Nolen, a custom furniture builder from Cody, remarked, “I’ll say one thing-the way they worked these logs was a lot of work. Skip-peeling logs to create that polka-dot effect took time.”

In furnishing the buildings, Dunrud and his helpers were probably not thinking of historical legacy. Their creations were the result of hard work, ingenuity and available materials. No agonizing over style, proportion, line, balance and scale. No tack rag wiping between coats of clear finish for this furniture. The lack of sophistication was its principal charm. It connects to something with which anyone who has ever loved cowboys, or who has ever attempted to build something with his own hands, can identify.

This is Cowboy Low Style furniture.

Dunrud and his ranch hands quickly crafted beds, davenports, tables, benches, wood boxes and pole racks for saddles. One particularly attractive little table was painted with red and green polka-dots before shellac was applied. Time stands still in this old furniture. And in the end, something accidentally beautiful and wonderfully enduring was created.

Dunrud closed the dude ranch in 1941 when tourism fell off as the country’s attention turned to World War II. He sold out around 1947. Eventually, the ranch was purchased by Amax, a mineral mining company. Because of the unprofitability and environmental concerns, it was sold to another owner and donated through the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to the United States Forest Service, which owns, preserves and administers the site today.

The Forest Service’s plan to stabilize and clean up the site has been helped along by volunteer caretaker Jim McGregor, who has lived there for the past two seasons. He sees the place as embodying Wyoming tradition. “I don’t want to sound stuffy, but this place is important beyond just the buildings and the furnishings,” McGregor observed. “This is a microcosm of what people did in Wyoming. They tried this and that and they bucked the odds. There was wrestling to make do. You can see here that ideas came to this valley-they washed in-and this was the beach they washed up on. It’s still all intact here, more or less.”

About the author

Joanita Monteith was a Buffalo Bill Center of the West volunteer. She moved to Cody from South Dakota in 1997, where she served as executive director of the Codington County Historical Society and its museums.

Post 121

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.