Star Quilts — “A Thing of Beauty” – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Summer 2004

Star Quilts — “A Thing of Beauty”

By Anne Marie Shriver

Former Web Content Developer; current Executive Assistant to the Executive Director and the Board of Trustees

These are notes to lightning in my bedroom.

A star forged from linen thread and patches.

Purple, yellow, red like diamond suckers, children

of the star gleam on sweaty nights. The quilt unfolds

against sheets, moving, warm clouds of Chinook.

It covers my cuts, my red birch clusters under pine.

—From the poem Star Quilt by Roberta Hill Whiteman, Oneida, 1984.1

As if lying against a night sky, the center star explodes from its background in a dynamic burst of pattern and color. Flawless in its execution, the eight-pointed star in the center of the quilt reflects the care and skill of its maker. The projecting design recalls the circles of eagle feather bonnets, the rays of the sun, and the morning star—all of which are found on painted buffalo robes from the past. The star quilt is an ironic example of the transformation of an adopted art form.

The star quilt, adapted from the Star of Bethlehem design found in Pennsylvania, seems to have become a reflection of Lakota society, both historically and in modern times. Like the painted buffalo robes made by women to be worn by men, star quilts are used today for momentous occasions or exchanged as gifts of honor. These quilts have become integrated into every aspect of Lakota life, and are used whenever people hold celebrations perceived as traditional—including naming ceremonies, weddings, births and basketball tournaments. It is also common to drape the coffin with a star quilt during a wake.

Lakota women spend the whole year making star quilts for the traditional giveaways held by their people. A giveaway is a public way of honoring others, particularly relatives.2

Though introduced to the Lakota people from outside of their traditions, quiltmaking has become thoroughly embedded in Lakota life. Quilts, and especially those in the star pattern, are one of the definitive cultural symbols of the Lakota people.3 The star quilt, made from raw materials initially traded for and now purchased from non-Indians, has become the singular piece of artwork that is a symbol of being Lakota in the modern world. Thus the traditional role of women as artists and craftsmen is still very important, as all Lakota people require an abundance of star quilts over their lifetimes.4

In the early part of the nineteenth century, military people, pioneers, gold seekers and missionaries began to settle the domain of the Lakota people—what is now North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana. With the loss of their land and disappearance of their food supply—the once vast herds of bison—Native people were placed on reservations and expected to forget their cultural, domestic, and religious traditions. It was the government’s desire to have the once nomadic, hunting Lakota of the Plains become farmers on designated plots of land.

As part of the United States government’s attempt to assimilate American Indian children into mainstream American life, boys and girls were sent to missionary or government-run boarding schools—far from the reservation and their families. The older children divided their days into academic and vocational classes. Girls concentrated on gaining skills in the domestic arts, such as laundry, food preparation and sewing—including quiltmaking. Boys learned about animal husbandry, farming, and other vocational skills.

As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth on the reservations, government programs were teaching Native men and women farming and domestic skills, similar to what their children were being taught at the boarding schools. The Field Matron Program, established by the Office of Indian Affairs, promoted assimilation through intensive domestic work with Indian women in reservation communities. Field matrons, including a few Native American women, spent much of their time working with tribal women on cooking, housekeeping and sewing skills. These three subjects were thought to be the most useful and afforded the field matrons their best chance for successful cultural transmission.5

Oglala Lakota artist, educator and historian Arthur Amiotte asserts that the young women from boarding schools returned to the reservation with homemaking skills commensurate with those being taught in the communities, albeit with more detail and sophistication. The institutional settings allowed for more precision with the sewing machines, and the materials were more in line with non-Indian homemaking conventions and fashions. Literacy offered further options for the educated Native American homemaker, as she could now order a variety of materials from mail order businesses such as Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck and Company.

According to Amiotte it was around this time that the patchwork or crazy quilt emerged as an alternative to expensive purchased blankets.

The recycling of cloth was important, and these early quilts were made from old clothing, muslin, flour and salt sacks, and filled with coarse burlap feed and potato sacks. Used clothing sent to denominational missions by Eastern benefactors found their way into colorful quilts. Particularly functional were those made of fine broadcloth, serge and flannel wool. The female tradition of designing in straight edged geometric seems to have made this a natural transition, as the early quilts were predominantly geometric blocks reminiscent of the designs found in parfleches, quillwork and beadwork.6

Amiotte emphasizes that the radiating star quilt design, which is also a favored by numerous American Indian tribes, did not gain its popularity and ascribed tribal significance until the 1950s. Other scholars, such as Beatrice Medicine and Patricia Albers, believe that Lakota women have been influential in adapting a rather new art form of quilting to an old traditional art form – hide painting. They affirm the star quilt pattern is descended from ceremonial hide robes bearing the morning star design.7 However, as maintained by Amiotte, the cultural motif associated with the morning star was of a certain generation; women producing this pattern today were not exposed to this during their childhood.

At the tribal fairs and giveaways in the first two decades of the 1900s, Amiotte’s study has found, the quilts made for giving away were only the newly made quilt tops. Recipients then took these home and recovered existing quilts as fillers. It is not unusual in disassembling heirloom quilts to find several layers of beautifully blocked and sewn previous quilt tops. It was customary every year to remove the top and backing of these tied quilts and launder them and re-assemble for use, sometimes using a newly sewn quilt top to replace the previous one. The sewing machine, available at the mercantile on or near the reservation, greatly augmented the production of quilts, which, in some cases, became a medium of exchange in some bartering transactions.8

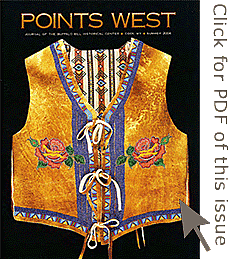

The collections of the Plains Indian Museum include a number of beautiful quilts, including a star quilt, featured with this article, by Freda Mesteth Goodsell, Oglala Lakota artist. An interview with Mrs. Goodsell and her nephew, Arthur Amiotte, gives insight into the creation of these artworks. Mrs. Goodsell was born to Christina Standing Bear Mesteth and George Mesteth in a log house on White Horse Creek, south of Manderson, South Dakota. Built in 1919 by her grandparents, Standing Bear and Louise Renwick Standing Bear, the house is featured in the Adversity and Renewal gallery in the Plains Indian Museum.

Quilting has become embedded in Lakota life, and typically the art is learned at home, usually from an elder. Mrs. Goodsell states, “My mother was a quiltmaker, so I grew up with it.” Interestingly, she did not take up quilting until she was in her thirties. “I saw these beautiful quilts and was wishing for one, and I thought I’m going to go home and make one. I taught myself.”

When asked for an approximation of quilts she has produced, Mrs. Goodsell was not able to give a number. Since beginning in her 30’s, Mrs. Goodsell has most likely made thousands of quilts. Mrs. Goodsell makes quilts for ceremonies, sometimes forty or fifty at a time, and for family and friends. She also donates quilts for fundraising purposes, such as when neighbors need help covering medical expenses or when her granddaughter’s volleyball team was raising money to go to Australia for a tournament. “It is a status symbol to receive a well made star quilt, because of the craftsmanship and beauty. It is also a tribute to the maker,” says Arthur Amiotte.

Mrs. Goodsell machine pieces the body of the star, and the body is entirely hand quilted. Her intuitive sense of design and color is visible in all of her quilts. The color inspiration for a quilt is quite interesting, Mrs. Goodsell says, “I make quilts like how I dress,” and her nephew interjects, “Well coordinated!” The sewing room, converted from a bedroom by her husband, contains neatly organized shelves that are all color coordinated, “like a color chart.” Amiotte emphasizes that “looking at the stacks of fabric is like looking at a rainbow. There are hundreds of tones in each hue.” Mrs. Goodsell emphasizes, “There are lots of colors, and you would not believe the number of whites available.”

Mrs. Goodsell is now also making applique quilts, and as she has recently created a quilt for members of the Korczak Ziolkowski family at the Crazy Horse Memorial in South Dakota. She had fun making an outline of the ten members of the family “using little pieces of their own garments, and I made a scene where they look like gingerbread men.” She also creates applique quilts with eagles and bison.

In addition to being a master quilter, Mrs. Goodsell started making traditional dolls “about twenty years ago.” Some of these wonderful pieces are also in the Plains Indian Museum collections.

“My mother taught us beadwork, and my mother made us dolls.” According to Amiotte, these “piece dolls” were made from leftover pieces of quilts and were stuffed with cotton from mattresses. They did not have faces – so the child could use their imagination as to what the doll might look like.9

Although quilting is a rather recent phenomenon in Lakota society, the star quilt has become an essential part of Lakota cultural and artistic traditions. Freda Goodsell says she is personally inspired to make star quilts because they are “a thing of beauty.” In the hands of this artist, they are indeed.

Notes

1. Roberta Hill Whiteman, “Star Quilt,” in Native American Literature: A Brief Introduction and Anthology, ed. Gerald Vizenor (New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1995), 268-269.

2. Emil Her Many Horses, “Rosebud Quilts: Building a Museum Collection, Creating an Exhibition,” in To Honor and Comfort: Native Quilting Traditions, eds. Marsha L. MacDowell and C. Kurt Dewhurst (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1997), 165.

3. Laurie N. Anderson, “Learning the Threads: Sioux Quiltmaking in South Dakota,” in To Honor and Comfort: Native Quilting Traditions, eds. Marsha L. MacDowell and C. Kurt Dewhurst (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1997), 101.

4. Marla N. Powers, Oglala Women: Myth, Ritual, and Reality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 139.

5. L.E. Emmerich, “‘Right in the Midst of My Own People’: Native American Women and the Field Matron Program.” American Indian Quarterly, 15, no. 2 (Spring 91): 201-217.

6. Arthur Amiotte, “Lakota People in the Early Reservation Era: 1850-1930”, unpublished manuscript, Plains Indian Museum, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 2004.

7. Patricia Albers and Beatrice Medicine, “The Role of Sioux Women in the Production of Ceremonial Objects: The Case of the Star Quilt,” in The Hidden Half: Studies of Plains Indian Women. (Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1983), 124.

8. Ibid.

9. (12 February, 2004). Personal interview with Freda Goodsell and Arthur Amiotte.

Post 124

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.