Unloading the Six-Shooter – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2011

Unloading the Six-Shooter: Disassembling the Glamorization and Demonization of Firearms in the Arts

By Ashley Hlebinsky

Curator, Cody Firearms Museum

Imagine a scene from the Old West in Dodge City, Kansas: Two men face each other in a showdown in which only the one with a quicker Colt Peacemaker will survive. The tension from this scene leads to excitement.

Now imagine a theatre stage: One man dreams of a future, while another raises a Luger and with trembling hand, pulls the trigger. The tragedy in this scene is palpable.

These scenes—the first from the opening of the popular CBS television series Gunsmoke and the second from the stage adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men—are examples of the dissonance between the effects loaded firearms have on audiences of western cinema as opposed to those of dramatic theatre. The six different ways that firearms are portrayed shape audience perceptions and produce loaded emotions. To understand these feelings, let’s load that single action six-shooter and fire the rounds that shape audience perceptions.

Round 1: The firepower effect

Round 1 is chambered and fired with a “bang,” startling audiences unaccustomed to gunfire.

Those in western cinema, as well as dramatic theatre, are totally aware of this “firepower effect” and introduce firearms in diverse ways to manipulate audiences.

Westerns, since their inception following Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, have used firearm desensitization to acclimate audiences to gunfire so that they won’t recoil from the experience. Many western films and television series like Gunsmoke use firearms early and continuously in order to induce the Freudian concept of repetition compulsion. This is a subconscious act of replaying a traumatic event in order to cope with it. Frontier plays—a branch of melodramatic theatre popular in the 1830s and 1840s that depicted the American West—follow this pattern.

Frontier and modern plays like Robert Schenkhan’s Kentucky Cycle (1992) bridge the gap between westerns and theatre while other forms of dramatic theatre disagree with the use of firearms desensitization. Dramatic plays typically introduce firearms through the use of the literary device, “Chekhov’s Gun,” that is, the introduction of a prop early in the performance to foreshadow later events. For example, Steinbeck references a Luger early in Of Mice and Men to foreshadow its reappearance at the end of the story. Some theatres also provide gunfire warning notices in their lobbies prior to performances. These notices have the power both to warn and keep an audience “on edge throughout” the play according to England’s newspaper The Guardian, 2011.

Western cinema and dramatic theatre introduce firearms differently to establish contrasting perceptions. Throughout the plot, those actors who choose to arm themselves further develop these ideas.

Round 2: The man behind the gun

As Round 2 fires, villains, heroes, and troubled protagonists confront the audience.

Sometimes, in both media (western movies and theatre), villains—whether by black Stetson or disposition—are easily identifiable. Westerns depict villains as inhuman predators that “learn by the taste of wounds” (Have Gun Will Travel, 1970). They embody wild, animalistic imagery to diminish audience empathy. Often referred to as “animals,” these villains commit crimes that do not “take anyman at all” (Gunsmoke, 1969). This same imagery can be seen on the stage. In Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1972), mobster Arturo Ui destroys his enemies with a hail of bullets from submachine guns. Any type of firearm though, in the hands of a villain, is considered a weapon.

Apart from their animalistic alter egos, heroes in westerns are depicted as humans with potential to become predators. All heroes possess a “cat claw” (Have Gun Will Travel, 1970) or the same type of predatory animalism found in villains. Heroes possess the restraint to retract their claws until being forced to act. The actual action of pulling the trigger also sets them apart. Western heroes’ shooting skills elevate them in communities that enjoy “any excitement…a gunfight might bring” (Lenihan, 1980). But, as the smoke clears, these communities typically reject heroes who do not belong to law enforcement.

On the other hand, heroes accepted by communities can become troubled protagonists through the lure of corruption. In both Howard Hawks’s western film Red River (1948) and the stage adaptation of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men (1948), the initial heroes—cattle rancher Thomas Dunson and aspiring politician Willie Stark, respectively—abuse their authority. While Red River‘s hero realizes the error of his ways and eventually reforms, the latter hero is shot before he can do the same.

As other heroes are forced to separate from society, they can succumb to instinctual brutality. Some heroes like Billy Ringo in The Gunbelt (1953) trade their firearms for family in an attempt to join civilization. They become troubled, though, when they realize their violent ways will always set them apart.

In theatre, the protagonist in Of Mice and Men experiences the opposite effect. In order to remain a part of society, he is forced to shoot a friend who has become dangerous. While their circumstances differ, all these men make the conscious choice to use firearms.

Round 3: Cheating the shot

Round 3 targets the many roles firearms play in both western cinema and dramatic theatre.

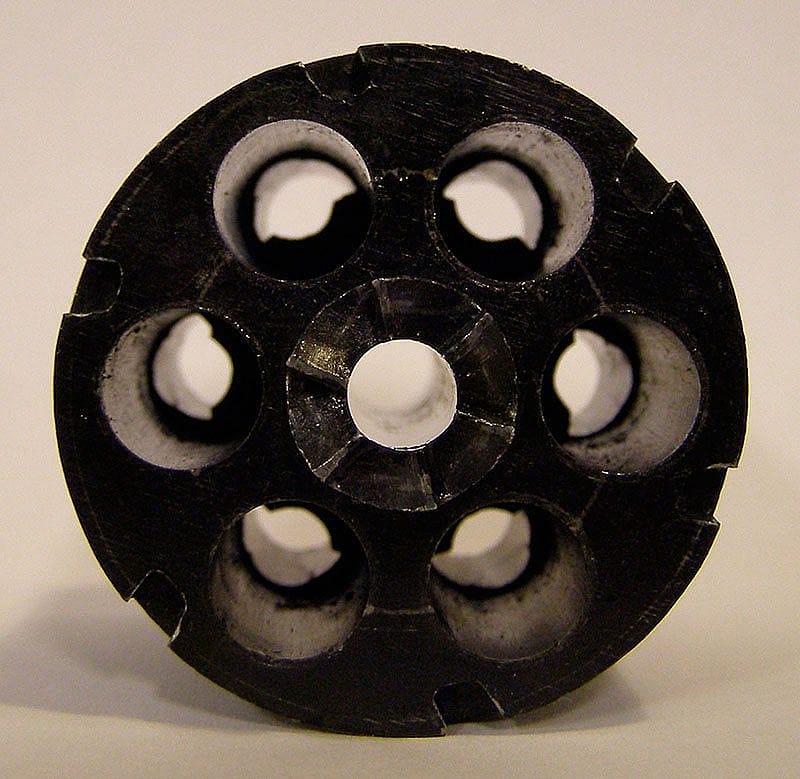

The role of safety is prominent in both western films and television, and in dramatic theatre. Designated firearms masters securely maintain a combination of rubber props and converted guns. Blank cartridges have been used from as early as 1914; blanks are still considered dangerous and are never fired directly at an actor—”cheating the shot” to the left or to the right. Moreover, a restricted cylinder can be used in which the chambers narrow at the end to ensure no live ammunition can be loaded.

The role of diversity in firearms choices and their accuracy is questionable. Dramatic theatre uses many types of firearms, including but not limited to Lugers (Of Mice and Men), Brownings (The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui), and Smith and Wessons (All the King’’ Men). While some westerns like Gunsmoke periodically reference multiple firearms companies like Remington, Springfield, Smith and Wesson, and Sharps, many strictly employ Model 1873 Colt Peacemakers (.45/.44-40 caliber single action six-shooters) and Model 1873 Winchester rifles (.44-40 caliber lever action repeaters). The films The Iron Horse (1924) and The Plainsman (1937) both feature Peacemakers despite being set in the 1860s when the Colt Model 1860 Army would have been used. In an attempt to feign accuracy when screen actors are unable to achieve desired shots, they receive double action revolvers, making it easier to complete scenes which are edited to appear authentic.

The role firearms often play in dramatic theatre is the demonization of violence as a way to intimidate. In westerns, on the other hand, firearms have played a glamorized role since the quick-draw cowboy emerged who, within seconds, could reach into his holster, hook his thumb on the hammer, pull the trigger, release, and fire. In reality, quick draws, along with “fanning”—the process of pressing the trigger while rapidly slapping the hammer—are considered inaccurate and dangerous. While today’s sport of Cowboy Action Shooting has proved these methods possible, a 1938 firearms handbook says it best: “Leave Wild West Stunts to the Shade of the Old Bad Man—who probably never pulled them.”

The role of the mere presence of a firearm deeply impacts audiences as well due to the belief that “if there’s a gun being toted in one’s vicinity, one seldom focuses elsewhere” (The Guardian). While some audience members can become so engrossed in a film that they forget it is fiction, audiences typically view the screen as a shield from actual danger. Theatre audiences do not have that separation, so the presence and sounds of firearms can be unnerving.

Round 4: The Big Bang Theory

Listen closely as Round 4 is chambered and experience the sound. While audiences of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West were said to be accustomed to the “ringing cheer” of the “bang bang bang,” audiences of the early days of western film and dramatic theatre were unfamiliar with it.

The transition from silent to sound films in the 1920s was difficult for audience members who were not used to sounds at the cinema. To facilitate their adjustment, western films gradually transitioned. By 1928, The Big Hop and Land of the Silver Fox were the first westerns to experiment with sound. By the 1930s, film audiences had adjusted and cheered the “bang, bang” commotion like they had in the days of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

Dramatic theatre audiences, however, are still unnerved by the “earsplitting, heart-[jarring] pop” (The Guardian) of a Luger in Of Mice and Men, or the “rat-tat-tat” of a submachine gun in The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. These sounds signify tragedy. In some cases the firearm is both seen and heard, but in others, such as All the King’s Men, the bang reverberates offstage while the audience waits to see the victim.

Round 5: A vanishing victim?

And firing Round 5 produces that victim. Manipulated empathy and depictions of gore can alter audience perceptions of firearms.

As previously mentioned, villains are often easy to identify in westerns, but to ensure their deaths are not mourned, they vanish from screen. Vanishing victims provide “a failure of empathy” that allows the audience to cope with violence and understand simple morality.

Along with heroes and villains, the role of victims over time has evolved. The 1953 movie Shane was the first western to use wires to jerk the victim to simulate the effect a firearm would have on him. Television series Gunsmoke, High Chapparal, and Have Gun Will Travel, often depicted scenes where, according to stage directions, a victim “hunches slightly” so the audience can see “two spots of blood growing” and in the blink of an eye, “his blood is saturating” his clothing. Including victims in the story line causes the audience to witness consequence and to question justifiability. The consequence in some cases, as in All the King’s Men, is portrayed as unjustifiable, resulting in the gunman’s suicide. The emergence of the concept of consequence is a result of the society surrounding an audience.

Round 6: The casualty of war

Firing Round 6 reveals the effect war has had in the arts and subsequently on firearm perceptions.

A new America emerged from the ashes of the Civil War, yet the country remained divided in the arts. War time violence initiated the realism movement in American dramatic theatre, while the stereotypical depictions of the American West emerged in the search for national identity. After two World Wars, stereotypical westerns embraced realism. While maintaining some stereotypical swagger, they now exhibited Shakespearean torment. Western films such as Red River and High Noon (1953) coincide thematically with dramatic theatre productions, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui and All the King’s Men, all dealing with abuses of power that eerily mirror the rise of men like Hitler and the corruption of government.

These internal conflicts eventually translated into external violence on screen and stage, reminding Americans of images of the Vietnam War. Appearing in the Los Angeles Times in 1969, one reviewer wrote that Gunsmoke was known for “violence—the quick, sudden kind [that] made the viewer queasy,” while another wrote in 1982 that “audiences complained that it had become increasingly difficult to assess how much is too much” in terms of firearm use and violence—two terms which became synonymous.

As media portrayals of violence increased, protests about firearm use emerged. In order to call into question the audience’s role as spectator, performance artist Chris Burden’s 1971 video Shoot records audience reaction as they witness him being shot in the arm. Despite viewers being present, no one attempts to intervene for his safety.

Firearms violence in news media is manipulated on both sides to serve artistic purposes. The 2011 play O Beautiful by Theresa Rebeck explores the story of “a kid who loathes himself, [and] a loaded gun.” On the other side, even westerns begin to demonize firearms, exhibiting higher levels of violence in films such as No Country for Old Men (2007). While audiences still love western firearms on screen, many now condemn them when used in reality.

After firing these six rounds, there is no bang, no fear, no danger—just an unloaded gun that ceases to be a metaphor for violence and can now be studied objectively. As objects, they become both art and educational tools to teach about safety, history, and society. Without the ability to recognize unloaded firearms apart from their loaded cinematic and theatrical alter egos, the lessons these objects can teach run the risk of becoming victims themselves.

About the author

As both an intern with the Cody Firearms Museum, and a Center Resident Fellow, Hlebinsky studied the Hollywood gun exhibit and visitors’ reactions to it, and worked in the McCracken Research Library to gather information about the firearms facet of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

Hlebinsky has worked for the firearms curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and earned her master’s degree in history and museum studies from the University of Delaware. Hlebinsky served as the Cody Firearms Museum’s Robert W. Woodruff Curator from 2015 to mid-2020. She is now Curator Emerita and Senior Firearms Scholar.

Post 126

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.