W.H.D. Koerner – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Fall 2002

W.H.D. Koerner: “In My Mind’s Eye,” An Artist’s Approach

By Julie Coleman Tachick

Former Curatorial Assistant, Whitney Western Art Museum

“I try to draw the man the author describes…. I concentrate on the character until it comes alive and I can see him in my mind’s eye.” —W.H.D. Koerner(1)

W.H.D. Koerner found his niche as an illustrator in the overwhelming popularity of the western adventure story. This type of art, however, was often criticized as merely illustration, implying a lack of creativity on the part of the artist because he/she did not necessarily originate the subject matter. For Koerner, the pictures he created to tell the story were conceived and given life in his “mind’s eye.”

In the June 25, 1932 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, Wesley Stout’s article, “Yes, We Read the Story,” directly addressed the ever-so-popular, yet often innocent question continually posed to illustrators at the time: “do you read the story?” Stout’s matter-of-fact essay, based on interviews with illustrators for the Post, including Koerner, discussed their methods of production and revealed to readers that illustrators not only read the story, they literally dissected and ingested it. Stout explained that illustrators took extensive notes on the characters and the picture possibilities, noting the period and scene. He pointed out that like the authors, illustrators read the narrative with great care and pride. But Stout reasoned the similarities ended there. How illustrators approached the final product—their artistic process—varied as differently as the authors’ styles of writing. The process itself was indeed one of creativity.

At the time of Stout’s interview, Koerner was working on Hal G. Evarts’ newest serial, “Short Grass,” a story about the final glory days of the open range.(2) As an illustrator, Koerner was commissioned to produce suitable illustrations for popular fiction. To meet this objective, he executed a precise, methodical working process, which began by reading the text. After he had read the story, he took notes on its setting, time and characters. Although the general period of “Short Grass” was evident, Evarts had attached no obvious date to the story, only a clue. The author spoke of a character having later played a part in the Johnson County cattle war, which led Koerner to conclude the period was prior to 1892. From this information, Koerner could depict the appropriate style of clothing worn by the cowboys during this time of western settlement.

Next, he selected specific passages in the story to illustrate. For “Short Grass,” Koerner produced eighteen illustrations. He chose to base his painting, Hard Winter, on the passage: “The snow eddied and whirled about the men. They were muffled to the eyes by their neck scarfs. Night had descended by the time they returned to the ranch house.” Koerner preferred to make illustrations that would bring the text alive. When the article and illustration were printed, the passage would appear under the illustration, making an exact correlation between the text and image.

For inspiration in creating his imagery, Koerner studied the visual images of Frederic Remington, who ushered in and dominated The Golden Age of Illustrating until his death in 1909. Koerner also consulted his massive collection of clippings, large brown folders stuffed with photographic reproductions of western subject matter from magazines and newspapers. Then he did research, often in the New York Public Library and Museum of Natural History, as well as his own personal library. To create the main figure in the painting, Koerner relied upon his imagination and the author’s physical description of the character. Although he felt a model would hamper his creativity, he found it advantageous in fine-tuning subtle effects. As he recalled, “I may want to know exactly how the light falls upon an ear, or the precise twist of a head, but the model is only a lay figure to me.”(3) Koerner often dressed his children, Billy and Ruth, in costume and posed them to help capture the play of light on clothing and the shape of the human figure. In Hard Winter, Billy posed for the figure on horseback so his father could get the right modeling on the clothing worn by the cowboy. It was a sweltering July day, and “Little Billy Koerner” was swaddled in coats and scarves from head to toe. In order to help his son endure this very uncomfortable situation, Koerner told him the story surrounding the scene. Years later, his son vividly recalled the experience and remembered how much cooler he felt imagining the blizzard in the story.(4)

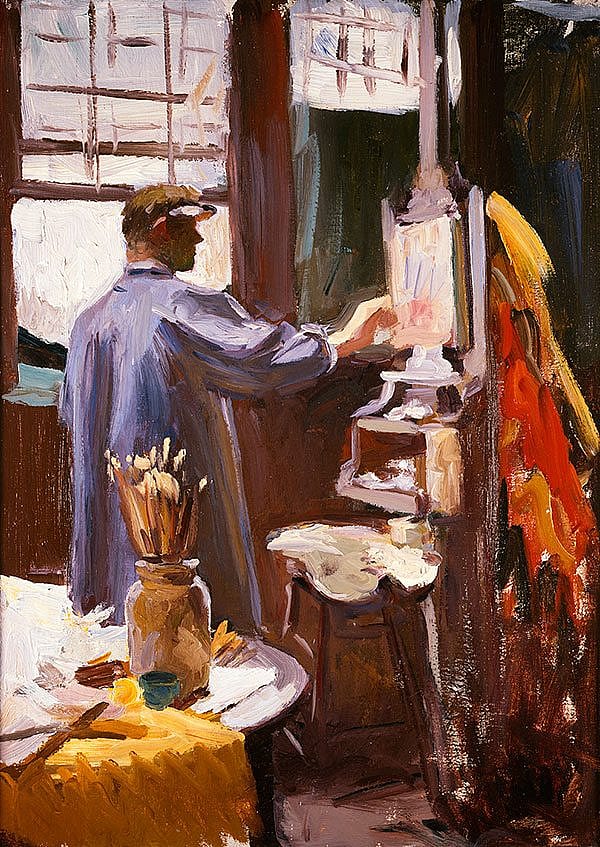

Armed with multiple bits of information and ideas, Koerner could now transfer to paper the image taking form in his mind. He usually made four or more 4 x 5 inches or slightly larger thumbnail and preparatory sketches both in pencil and in color until he felt the composition was correct for the painting he envisioned. Once he had the desired composition, he transferred it freehand in charcoal to his canvas. Using the paint generously, he painted freely and spontaneously with bold, strong strokes, sometimes using a palette knife or wide brush, well worn down, to obtain a “rich impasto” approach, which lent excitement to his strokes.(5) In order to get the effect he wanted, it was not uncommon for Koerner to combine a variety of media, ranging from charcoal, wax crayons, colored pencils, oils, watercolors and the hard “Mon Ami” pastels. He usually completed the entire painting within one week. Koerner did not need to paint in color, as many images would be reproduced in black and white. He painted with a full palette of color primarily because he saw the works as having a life beyond illustration. He felt they were complete works on their own. Even without the accompanying text, Koerner’s sweeping brush strokes, use of texture and muted color scheme in Hard Winter effectively captures and relays a story about the harsh, bitter winter conditions cowboys contend with on the western open range.

Born in Lunden, Germany in 1878, William Henry David Koerner (anglicized form) came with his family to Iowa in 1880. At the age of eighteen, he started his illustrative career as a professional illustrator for the Chicago Tribune. In 1907 Koerner went to Wilmington, Delaware to become a pupil of Howard Pyle, who had also mentored N.C. Wyeth and Harvey Dunn. Regarded as the greatest teacher of illustration in America, Pyle instilled a unique philosophy in his students. He emphasized imagination over copying from life, encouraging his students to go as far as possible without models, using them only to correct the drawing. He also stressed immersion in the subject and above all, a strong narrative thread to the picture. How paint was applied to the canvas was of little concern. Trained to create images that accompanied, amplified and effectively visualized written fiction, his pupils became masters at narrative art. The best illustrations were those that stood on their own as works of art. Pyle’s curriculum not only honed the skills and talents of his students, but also shaped the entire direction of Western art and illustration.

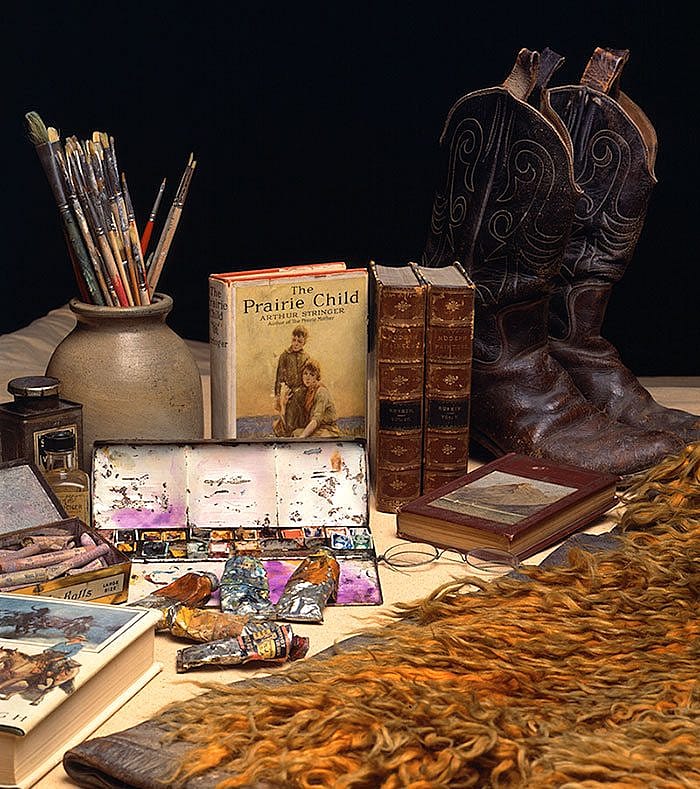

By the 1920s, the West had become an important setting for popular fiction, and the conflict and romance of the open frontier provided ample material for writers and publishers. Books and magazines, such as The Saturday Evening Post and Scribner’s, featured western fiction by popular authors. Illustrations were used to enhance the drama, excitement, and appeal of the narratives. Under Pyle’s tutelage, Koerner quickly developed a solid reputation of his own, specializing in western and outdoor themes, portrayed from his studio in Interlaken, New Jersey. Authenticity was extremely important to Koerner, and he went to great lengths to investigate and accurately portray the American West. He traveled with his family to see the western states first hand. While on these trips, he sketched the surroundings, snapped photographs, and collected artifacts. His intense desire for accuracy also led him to acquire a substantial and rich collection of costumes and accessories to use as props for his works. His close attention to detail and accuracy brought him many commissions for illustrations, particularly that of western subject matter for The Saturday Evening Post.

Until his death in 1938, Koerner had illustrated more than nine hundred articles, short stories and serial installments during his career. To achieve such status required respect and collaboration between author and illustrator, and Koerner worked hard not to compromise this relationship. He was careful to interpret what the author meant without giving the plot away, or distracting from it. His aim was to enhance, not jeopardize the reader’s interpretation. To spark excitement, he emphasized human drama in his works, and constructed compositions that focused on large central figures to bring forward important elements in the story.

Today, more than ever, Koerner’s paintings are not merely illustrations, but strong visual statements that stand on their own as significant works of art.

Notes:

(1) W.H.D. Koerner, as quoted in, Wesley Stout, “Yes, We Read the Story,” The Saturday Evening Post, June 25, 1932, p. 38.

(2) Hal G. Evarts, “Short Grass,” The Saturday Evening Post, May 21 – July 2, 1932.

(3) W.H.D. Koerner, as quoted in, “Yes, We Read the Story,” p. 38.

(4) William H.D. Koerner III, as told to Frances B. Clymer on August 19, 1993, Cody, Wyoming.

(5) W.H. Hutchinson, The World, The Work and The West of W.H.D. Koerner (University of Oklahoma Press, 1978), p. 134.

Post 129

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.