Alexander Phimister Proctor – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2004

Proctor: America’s Premier Sculptor of Western Animals and Horses

By Peter H. Hassrick,

Former Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar

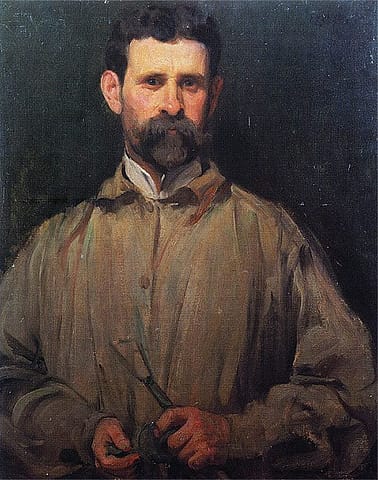

Alexander Phimister Proctor was known over a long and prosperous career as America’s premier sculptor of western animals and heroes. His career lasted nearly seventy years during a lifespan of almost ninety (1860 – 1950). Born in Canada and raised in Colorado, Proctor went on to study art in New York and Paris. He was an exponent of Beaux-arts, French romantic naturalism, throughout his life.

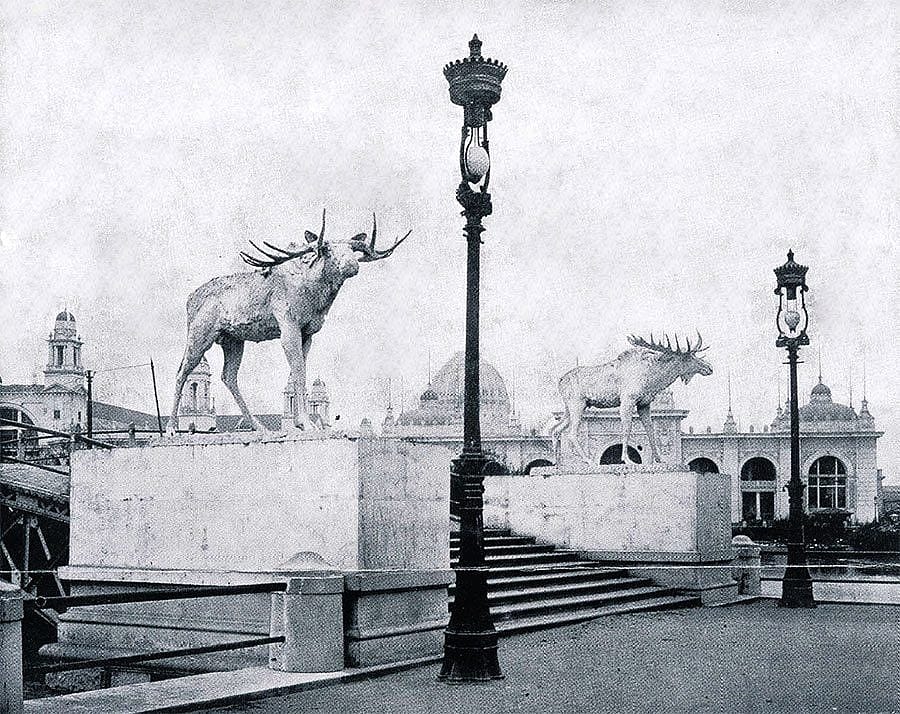

Proctor’s first success stemmed from his production of a bronze casting of a small fawn that was shown in New York’s Century Club in 1887. Frank D. Millet, who was later in charge of the decorations for the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (commonly called the Chicago World’s Fair), had seen it there and met the artist. In 1891, Millet would invite Proctor to be part of a team of artists to provide monumental plaster sculptures for the fair’s elaborate promenades. Proctor accepted an assignment to decorate the end posts of the fair’s bridges with heroic-sized animals from America’s western wilds. He would work side by side with the nation’s most esteemed sculptors. It was what he would term “my first big commission.”

Because his sculpture was inspired by French art, with his obvious indebtedness to master animalier Antoine Barye, Proctor would be regarded as one of New York’s “exponents of the modern tendency.” In hopes of building “a great national art,” practitioners were called upon to exercise spontaneity in their creative lives, and immediacy tailored perfectly for Proctor’s approach. This spontaneity found expression in Proctor’s work for the Chicago Exposition. Fairs like this were designed as venues for promoting nationalistic sentiments. This made Proctor, a student of the new American art and an advocate for the West’s native animals, a logical choice for such work. The original commission called for six animals to adorn bridges over the lagoons. By January 1, 1893, four months before the fair was to open, Proctor had completed eight pairs of animals. They were all judged “strong and purposeful to a remarkable degree.” Artist and historian Lorado Taft wrote that “few things in the entire exposition were more interesting or impressive than those great motionless creatures, the native American animals as sculpted by Proctor.”

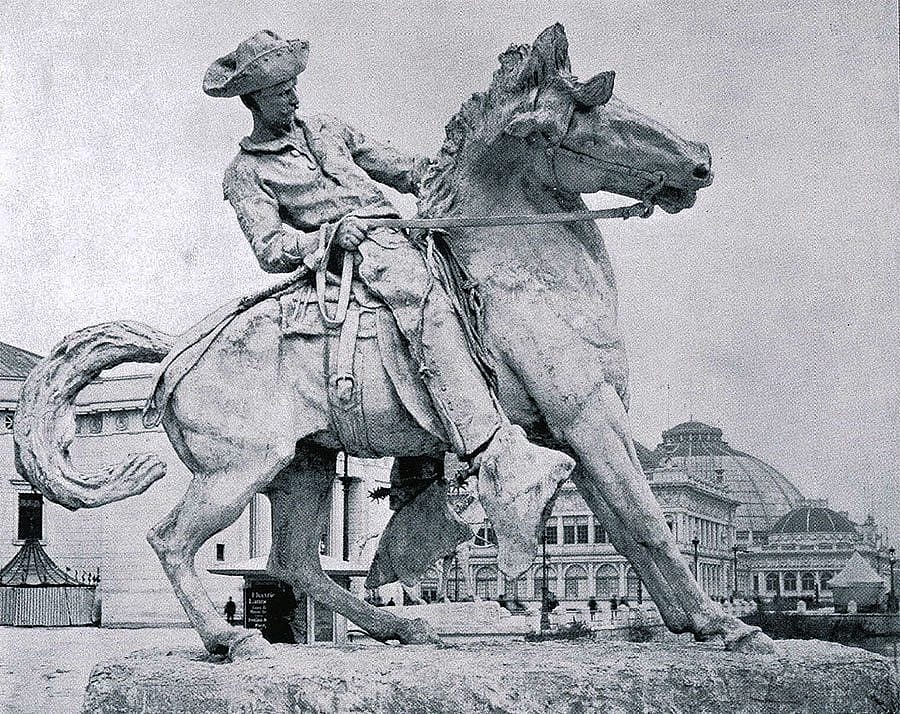

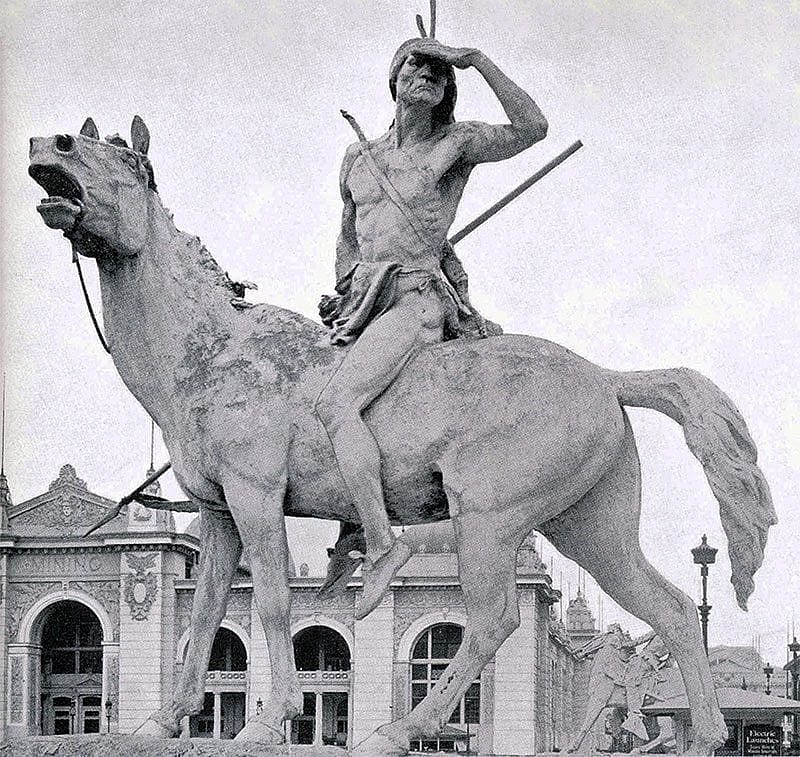

Once the animal commission was complete, Millet returned to Proctor with a further request. Now he asked the Colorado artist to create two equestrian plaster sculptures, one of a cowboy and the other of an Indian. For the cowboy group alone, Proctor protested, he would need at least a year. But Millet was persuasive and in a hurry, and Proctor completed the Cowboy in six weeks. The Indian was ready for the fair’s opening on May 1, 1893.

Proctor used the Chicago zoo to model his animals in combination with sketches from his Colorado fieldwork. He had shot and then drawn many elk, bear, and cougar. For the cowboy and Indian, ample sources were close at hand; camped just outside the exposition gates were William F. Cody and his Wild West troupe. Cody graciously offered performers from his exposition as models. The cowboy who posed (his identity is unknown) appeared to have been cooperative. The Indian model, Kills-Him-Twice, proved less so. Though “fierce and majestic,” according to Proctor, he was also petulant and impatient. The artist ended up using the Sioux Chief Red Cloud’s son, Jack, instead.

Once the fair opened and a few of the cowboys had visited the grounds, Proctor found he had a problem. On May 26 a Chicago newspaper reported that a group of Wild West cowboys had been gathered around Proctor’s Cowboy “having all kinds of fun criticizing the rider’s seat in the saddle and the ‘help! help!’ way in which the cowboy was hanging on to the reins.” They planned to sneak onto the fairgrounds and push the statue into the lagoon, that is, until Buffalo Bill learned of the plot and came to the rescue. He assembled the cowboys and advised them to mute their art criticism, since while “it was considered fashionable and perfectly correct to call things by their proper names on the other side of the Missouri, on this side a man had to be quite a graceful liar to be in good standing in society.” He admonished them that he would take it personally if the statue were molested. The scheme thus dissolved in grumbles. The cowboys had wanted literal transcriptions of nature and not artistic interpretations.

The Cowboy was Proctor’s first equestrian statue. It was also the first sculptural depiction of a cowboy in the history of American art. Its companion work, the Indian, was deemed more successful, though it was neither as original a composition nor was it the first of its kinds. Proctor’s big plasters did not go unnoticed. Among the dozens of monumental outdoor decorations, Proctor’s were judged by one writer “by far the most striking of all these impressive figures.”

The two sculptures symbolized the past. With their white plaster images reflected in the lagoon and silhouetted in front of Louis Sullivan’s avant-garde Transportation Building, they provided a brilliant emblem of loss and change. Like the Indian, the cowboy in 1893 was seen as a dying breed. Both figures and several of the species of large animals with which Proctor had decorated the bridges, as well as the frontier itself, had been proclaimed that year as part of a passing scene. For that reason Proctor was singled out among a legion of sculptors to eulogize a region, its people, their cultures, and even nature itself. As one writer penned after seeing the works of Proctor at the fair, “He is a Western man and he naturally seized Western types, because, after all, the West is nearer to nature than we of the East can ever be.”

On an island in the lagoon, connected to the massive Beaux-arts buildings by a bridge decorated with two of Proctor’s guardian elks, stood a small, rustic log structure called the “Hunters’ Cabin.” It served as headquarters for the Boone and Crockett Club, an organization that sought to do something about nature’s perceived demise. Proctor was inducted into the club that year. Although not the first artist to join (Albert Bierstadt was a charter member), he proved a loyal and zealous cadet. He welcomed the opportunity to address the increasing feminization of American culture (most of the animals depicted at the fair, for example, were male) and to resist the threatening encroachment of civilization on wilderness areas.

The impact of Chicago’s Exposition was far-reaching, not only for American cultural history but also for individual artists like Proctor. It provided a springboard for his, and many others’ careers. It also put money in his pocket, gave him enough credibility as an aspiring artist to enable him to win the hand of a fellow sculptor at the fair, Margaret Gerow, and afforded him an opportunity to further his studies in Europe. In October 1893, as plans were being made to ship his Cowboy and Indian plasters to Denver for extended display in their city park, Proctor and his bride boarded the City of Paris for France. Ten years later, art critic Roberta Balfour would note Proctor’s promise at this time:

The cowboy, puma and Indian, treated as Proctor treated them, were new subjects for the art critics. Ere the world’s fair ended it was authoritatively announced and generally conceded that Proctor was the greatest of young American sculptors.

Proctor returned to America permanently in 1900. He began immediately to produce animal sculptures for influential gentlemen like Henry Frick and Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney. Proctor’s 1907 cast of a bull moose was originally modeled for his old friend Gifford Pinchot. The two men shared affection for nature and interest in the preservation of its wonders. Serving as Roosevelt’s chief of the federal Forestry Division, Pinchot had just that year coined the word “conservation.” He and the President were about to embark on a national program of managed natural resources that would revolutionize American use of public lands. The moose was emblematic of their efforts.

The predecessors to Proctor’s Moose also had associations with conservation. Fourteen years earlier Proctor had sculpted four large plaster moose for the bridges to the “Wooded Island” and Roosevelt’s “Hunters’ Cabin,” built to promote his nascent Boone and Crockett Club and accommodate its meetings.

One of the souvenir albums that illustrated Proctor’s Chicago Moose claimed it was commonly believed in 1893 that the animals were on the verge of extinction. The declared mandate of the Boone and Crockett Club was to preserve huntable populations of America’s game animals, a mission with which the artist, as a sportsman, was in full accord. Proctor felt that his Chicago Moose symbolized both the glory of one of nature’s most eccentric forms and the hope for its continuance as a viable species. By 1907 Proctor’s skills were fully matured, and he felt confident that reworking the old model for the exposition Moose would produce good results. He was right; the new bronze succeeded in formally revitalizing and improving Proctor’s earlier composition.

On July 8, 1915, Proctor copyrighted his first bronze celebrating the American cowboy. He titled it Buckaroo, a term used in the Northwest to describe cowboys, especially those who rode and broke wild horses. In his autobiography Proctor acknowledge that this was his second attempt to produce an equestrian cowboy sculpture: “I had made one in plaster for the Columbian Exposition in Chicago twenty years before.” What he now had in mind, however, was dramatically different in pose and (at least to begin with) in scale. The result would be one of Proctor’s most successful and popular works.

Back in the spring of 1903, Proctor had received a long and cordial letter from an old Denver crony, Curtis Chamberlain. Proctor was pleased to hear from Chamberlain that his big Cowboy and Indian plasters were still standing in Denver’s City Park after a decade of exposure to the elements. The sculptures being made of plaster for the 1893 Exposition, he was amazed. “when I modeled those two groups,” Proctor responded, “I had no idea they would be in existence ten years from that date.” In his letter Chamberlain had also suggested that many citizens of Denver would enjoy having Proctor’s two sculptures redesigned and cast in bronze as a permanent part of the city’s landscape. Proctor answered with unreserved affirmation. Nothing came of this idea, but a seed had been planted that would someday sprout. A dozen years later, after a summer at the Pendleton Round-Up in Oregon. Proctor produced a small model for what would ultimately become his first permanent monumental sculpture. He titled it Buckaroo.

Proctor’s desire to eventually have the Buckaroo enlarged to over-life-size materialized some years later in Denver. The site was one of the most prominent possible: the city’s new Civic Center. This came about when Proctor and his wife, Margaret, arrived in Denver in late May 1917. They were there to attend Buffalo Bill’s funeral and to discuss with Denver’s Buffalo Bill Memorial Association ideas for a heroic-sized monument (that sadly never materialized) to the celebrated scout. To demonstrate his abilities with the human as well as the animal form, Proctor brought with him a casting of his Buckaroo. He presented the work to interested parties including the city’s dynamic mayor, Robert Walter Speer, who said he would be “proud to show this work of a former Denver boy to some of our wealthy citizens. I have no doubt Mr. [John K.] Mullen…may wish a life size figure of this subject for our Civic Center.”

Speer’s vision for monumental art in Denver, while including Proctor’s work, went well beyond that in scope. He had been impressed with the buildings and grounds at the exposition in Chicago. Inspired like other municipal builders of the era with the ensuing “City Beautiful” movement, Speer returned to Denver with a dream for the Queen City. Once he was elected mayor in 1904, he had the political clout to turn Denver into one of America’s flagship City Beautiful models. Speer persuaded Mullen a Denver miller, to give the Broncho Buster (as the monument was titled) to the city and convinced another benefactor, Stephen Knight, to donate its companion piece, an equestrian Indian, On the War Trail.

Over the next several decades, Proctor and his Broncho Buster continued to bolster Denver’s civic pride. Municipal Facts, a Denver promotional magazine, boasted in 1926 that the “Civic Center is conceded by artists to be the spoke of the most effective city plan in America,” and below a photograph of Proctor’s bronze silhouetted before silver-lined clouds, the magazine concluded grandly that “in a few years more…Denver will be generally acknowledge as ‘The Paris of America.'” Proctor had helped issue that passport to international acclaim even if it represented a leap nearly as large as that of the monument’s bucking horse.

Buffalo Bill’s loan of models and his defense of Proctor’s art back in 1893 had thus come full swing in supporting the sculptor’s aspirations to produce large-scale monuments to western heroes for public enjoyment in the West, Proctor went on to complete many more highly acclaimed monuments for cities like Kansas City, Wichita, Eugene, Salem, Pendleton, and Portland.

Post 137

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.