Proctor and Whitney – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2004

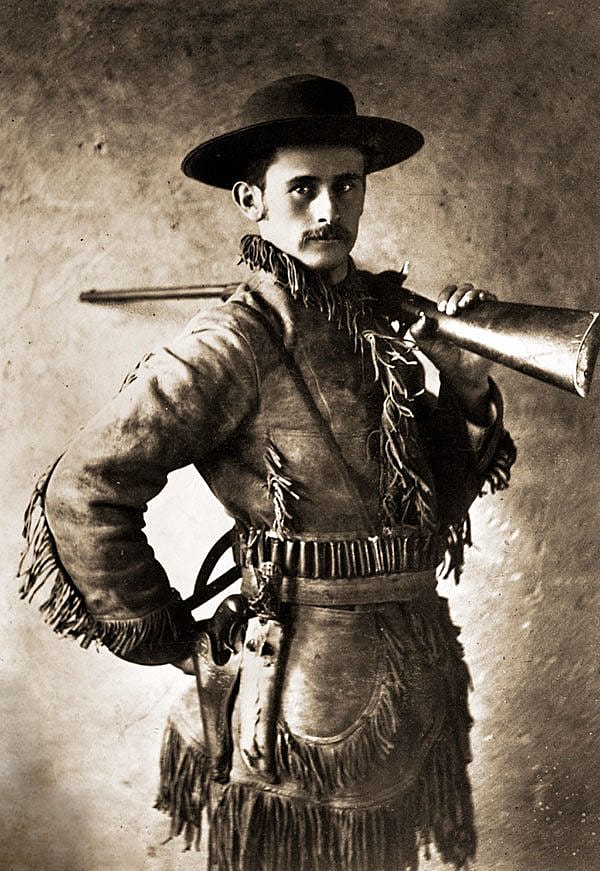

Alexander Phimister Proctor and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: Sculptor in Buckskin and American Princess

By Sarah E. Boehme

Former Curator, Whitney Western Art Museum

The art of sculpture has had an important role in the commemoration of heroic ideals throughout the history of art. Two American artists contributed significantly to heroic memorialization through their monumental works. Both Alexander Phimister Proctor (1860–1950) and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875–1942) devoted significant portions of their careers to monumental public sculpture, and each crafted important historical statements. They developed stylistically within the same tradition, yet created distinctive, individual works of art. At an important point in their careers, their studios were near each other, and each of these artists was approached to create a monument to William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Although their paths intertwined, they also veered in different directions. Comparing their careers reveals the differing ways that artists surmount obstacles in pursuit of an artistic vision.

With Proctor and Whitney, the circumstances of their births contrast vividly. One was a boy born to a family that had modest means and would live in the West, and the other was a girl born to a family of great wealth in the East. Alexander Phimister Proctor was born first, in 1860 in Canada.[1] He was the fourth son of Alexander and Tirzah Smith Proctor, who would have eleven children. The Proctors moved several times, settling in Colorado in 1871, where the father worked as a tailor and later had mining claims. Young Phim, as he was called, grew up with a yearning both for art and for the great outdoors. He drew and sketched, as well as hunted and fished. His father observed his talent in drawing, encouraged him, and arranged for art lessons. Phim attended public school through the eighth grade, then was apprenticed to J. Harrison Mills, a Denver artist and engraver, who would become a mentor for Proctor. Phim Proctor would spend summers at Grand Lake, Colorado, experiencing the rugged outdoors. In his autobiography, he wrote that “the most important event of my young life” was the day when, as a fourteen-year-old youth, he shot two deer, both bucks with “splendid” antlers.[2] He did not neglect his art, but used the experience to make sketches of the carcasses, and in this way, he learned animal anatomy. Proctor’s frontier persona would later lead him to be called the “sculptor in buckskin.”

Gertrude Vanderbilt was born in 1875 in New York City to Cornelius and Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt. She was the oldest surviving daughter (an older sister died in childhood) and would grow up with four brothers and a sister in a family with extraordinary wealth. Young Gertrude was educated at home by a governess, then at the Brearley School, and spent her summers in elegant Newport, Rhode Island. She sketched, but in her youth she seemed more inclined to be a writer than a visual artist. In her extensive written journals, she chronicled her experiences and confided her feelings. At an early age, she became aware of the effects of her family’s social position. In a penned autobiography, she wrote that she had learned “there were lots of things I could not do simply because I was Miss Vanderbilt.”[3] She felt the “burden of riches” and longed for a simpler life. Yet the family’s resources made it possible to travel to Europe where she visited and sketched in the great museums. The press styled Gertrude Vanderbilt as “the American princess.”[4]

Both Alexander Phimister Proctor and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney knew that education would be necessary to develop as artists and each obtained crucial art training in New York. For Proctor, it was necessary to go to New York to find instruction to develop his skills, but he did not have the finances to move. He tried mining to earn enough money to make the trip, and then sold his Colorado homestead. In 1885 he had the resources to move to the City and study painting. Proctor enrolled in a class at National Academy of Design, where the curriculum required him to draw meticulous copies from antique works. He extended his education by sketching wild animals at the city’s menagerie, so he balanced learning from the past with learning from nature. The following year he transferred to the Art Students League, where again the drawing classes stressed copying from the antique. Having been influenced by seeing the work of the great French animal sculptor, Antoine-Louis Barye, and the sculptural groupings of John Rogers, Proctor gradually began shifting his interest from painting to sculpture. New York City was important to him as a center for the arts, but his longing for the wilderness would take him to Colorado and other western areas in the summers.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney became more serious about the visual arts as an adult. After resuming her sketching, she gravitated toward sculpture. She first studied as she had as a young child, through private instruction. Through her social connections, she was introduced to Hendrik Andersen, a Norwegian-born artist whose family had settled in Newport, Rhode Island. Around 1900, he provided initial lessons in modeling and advice on producing sculpture to Gertrude. Later she, like Proctor, enrolled in New York’s largest and most significant school of art, the Art Students League. There she studied with James Earle Fraser, the sculptor now known for the sculpture of the dejected Indian, The End of the Trail, and also the designer of the Indian head and buffalo nickel.

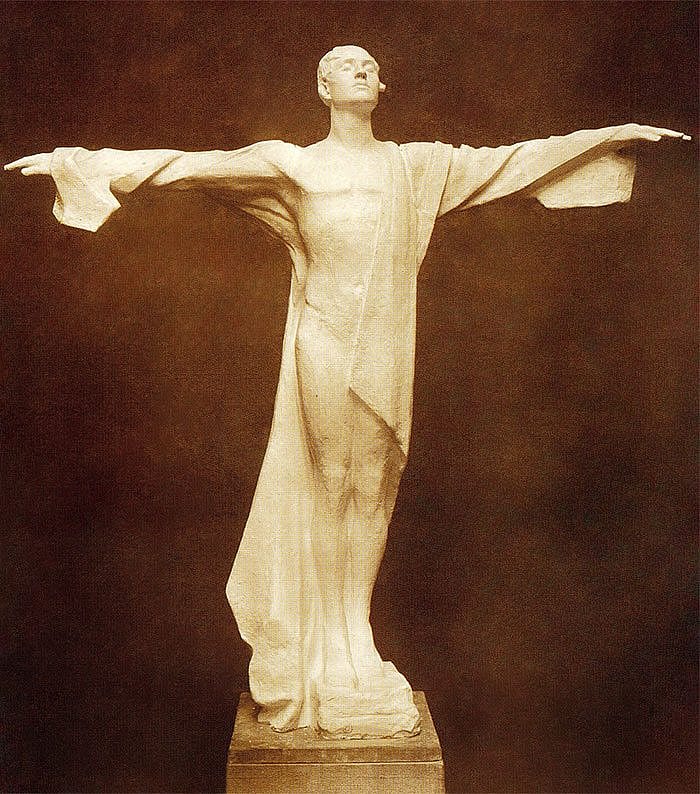

World’s fairs, the grand expositions that became popular leisure-time activities in the late nineteenth century, provided significant opportunities for artists to have their works of arts seen by the multitudes. Both Proctor and Whitney had important early exposure at such expositions. Proctor had his first important commission at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, and he would exhibit at other fairs, such as the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901, where he was also a judge. At that same Pan-American fair, Whitney showed her first large sculpture, Aspiration. These early successes at the Fairs gave both artists a taste of how sculpture could be integrated into cultural life, provided the opportunity to work in a large scale early in their careers, and opened up new possibilities for their work.

Marriage and family affected the lives of both these sculptors. Proctor met his future wife, Margaret (Mody) Gerow, in Chicago when he was working on the sculptures for the Exposition. Margaret Gerow, also an artist, was an assistant to sculptor Lorado Taft, when the two first met. They married in 1893 and Margaret Gerow Proctor gave up her artistic career to be a wife and mother to the eight children they would have. Alexander Phimister Proctor’s son Gifford Proctor (also a sculptor) acknowledged the importance of his mother’s role in his father’s success, saying that she freed him to do his work by taking on the cares of the family and the household, managing the many moves that they made, loving and encouraging him.[5]

Young Gertrude Vanderbilt and Harry Payne Whitney knew each other as young people whose families were in the same social circles since the Whitneys were also wealthy and socially prominent. The young couple became engaged during a visit to Florida and they married in 1896. Harry Payne Whitney, a law student then businessman, devoted much time and energy to his love of horses, horse racing and polo. It was during the early years of their marriage that Gertrude determined that she would not be confined to a life of social obligations but would pursue her art as a passion. Although other family members were not enthusiastic about her art efforts, her husband at first encouraged her to set up a studio and develop her talent, but it is thought that he saw her interest as a hobby.[6] The Whitneys had three children and Gertrude would later gain custody of her niece, Gloria Vanderbilt. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s financial resources made it possible for her to pursue her artistic career while still raising a family, yet her societal position meant that she was expected to maintain a certain established role, which was not that of professional artist.

Desire for more education led both artists to Europe. Proctor traveled to France in 1893 to study at the Académie Julian and although he would turn down the prestigious Prix de Rome, he would in 1925 have a studio at the American Academy in Rome. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney had a studio in Paris, where the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin visited her, gave her advice and encouragement, and influenced the style of her work.

Alexander Phimister Proctor and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney crossed paths when each established a studio in MacDougal Alley in Greenwich Village. The Alley attracted a coterie of artists who found the Village a congenial site. Proctor moved his studio there in 1904, the same year he was elected to membership in the National Academy of Design. At the urging of James Earle Fraser, Whitney scouted the area and found a stable at 19 MacDougal Alley, which she converted to a studio in 1907. Malvina Hoffman, who was working as an assistant to Proctor at that time, marveled at “the perfect order of Gertrude Whitney’s splendid place on the north side of the alley, with high, well-lighted studios and fully equipped workrooms. . . . Mrs. Whitney . . .worked tirelessly but was never too busy to help young sculptors; her generosity was well known to the profession.”[7] Hoffman’s admiration was not shared by all; Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was not really accepted by the other artists who seemed to consider her a wealthy amateur.[8]

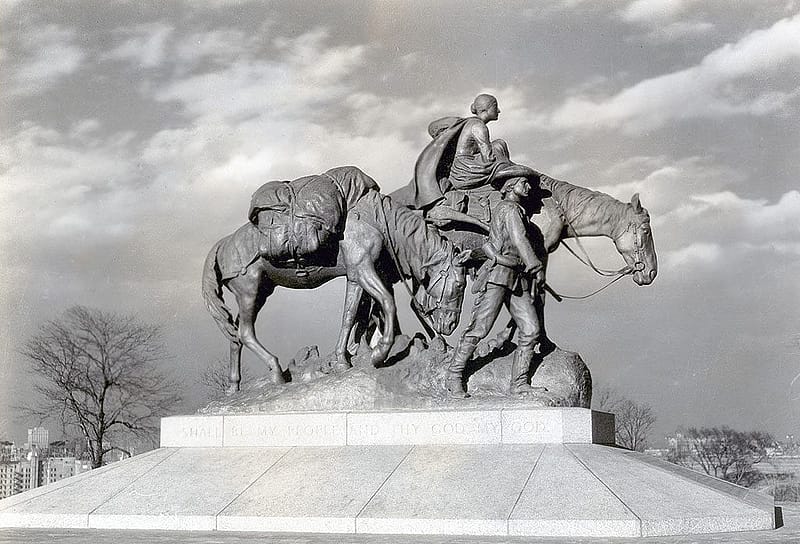

Although both Proctor and Whitney continued to develop as sculptors and to find individual success, they moved in different directions in the next decade. The West continued to have a strong hold on Proctor and he traveled to British Columbia, Montana and Oregon. The Pendleton Round-Up inspired him to create works such as the Broncho Buster, a tribute to the cowboy as an ideal of rugged fortitude. He so liked Oregon that he left New York and moved his family to Oregon in 1914 and there he would late receive important commissions for monuments such as the presidential hero, Theodore Roosevelt, and a religious leader, The Circuit Rider. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney solidified her New York roots, buying a building on Eighth Street that could be connected with the MacDougal Alley studio. There she began to show her collection of art, which would develop into the Whitney Museum of Art. In 1914 she was awarded the commission for the Titanic Memorial, a commemoration of the many people who had lost their lives in a tragic accident at sea. The war in Europe drew her concern and at the end of the year she sailed to France to aid in World War I relief efforts. After the war, she would produce several memorials to those who had sacrificed their lives, and she argued for the importance of memorials that would be dedicated only to preserving the memories of those who died and that would not be used for other purposes.[9]

Both Proctor and Whitney vied for the honor of producing a monument to William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. For a monument planned in Colorado shortly after Cody’s death in 1917, Theodore Roosevelt recommended Proctor, who had known Cody from the days of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Proctor drew a sketch, based on Wild West posters, but World War I interrupted the fundraising, the project never resumed, and Proctor went on to other projects, such as On the War Trail and the monument to Theodore Roosevelt.[10] Efforts for a memorial to Buffalo Bill in Wyoming were also started in 1917 when the Wyoming legislature voted a sum of $5000, but likewise seem to have stalled due to the war. In 1922, the townsfolk of Cody, Wyoming revived the project. Although Mary Jester Allen, a niece of Buffalo Bill, is often credited with initially approaching Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the suggestion for Whitney as artist came from publisher Col. Arthur W. Little, who spent time in Cody. Little and W.R. Coe, who had an estate on Long Island near Whitney’s home as well as property in Wyoming, presented the idea to Whitney.[11] Always eager to be taken seriously as an artist with a commission, Whitney was intrigued by the idea of a monument to Cody as a great American pioneer hero. Her efforts resulted in Buffalo Bill—The Scout, the dynamic sculpture installed in Cody, Wyoming in 1924.

Proctor and Whitney, two individuals seeking to become artists, encountered obstacles, but these roadblocks also became advantages. The modest circumstances of Proctor’s family introduced him to a life of hunting and the outdoors, which aided him in understanding anatomy and in emotionally connecting with ideas about frontier valor for works such as multi-figure Pioneer Mother. Whitney’s wealth and social connections, which had set her apart and made others unwilling to regard her as a serious artist, also helped her to secure commissions and to be able to carry them out, as in the case of the monument to Cody. The works of Alexander Phimister Proctor and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney will continue to inspire many generations of viewers who experience their heroic conceptions in public settings across the nation from east to west.

Notes:

1. See Peter H. Hassrick, Wildlife and Western Heroes: Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum in association with Third Millennium Publishing, 2003) for background on Proctor.

2. Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor in Buckskin: An Autobiography (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971) 31.

3. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, “My History” as quoted in B.H. Friedman, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc.: 1978) 5.

4. “Another Miss Vanderbilt: The Daughter of the Head of the House and Her Charities,” undated clipping, from the “Chicago Inter Ocean,” and “Just Like a Princess: Miss Gertrude Vanderbilt Is More Carefully Guarded than Maude of Wales,” San Francisco Examiner, c. 1896, Archives of American Art, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney papers.

5.”‘Needs Must When the Devil Drives’: Recollections of a Sculptor’s Son” by Gifford Proctor, in Hassrick, Wildlife and Western Heroes: Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor, 12 – 13.

6. Friedman, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, 171.

7. Malvina Hoffman, quoted in Friedman, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, 246.

8. Avis Berman, Rebels on Eighth Street: Juliana Force and the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York: Athenaeum, 1990) 77.

9. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, “The ‘Useless’ Memorial,” Art and Decoration, Vol. XII, no. 6, 421.

10. Hassrick, Wildlife and Western Heroes: Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor, 74.

11. “Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney Keen on Making Statue of Buffalo Bill,” Park County Enterprise, Feb. 8, 1922, 1.

Post 138

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.