Proctor as Storyteller – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2004

Tell Me a Story: Alexander Phimister Proctor as Storyteller

By Julie Tachick

Former Curatorial Assistant, Whitney Western Art Museum

Recognized during his lifetime as one of the leading sculptors of wildlife and western heroes, Alexander Phimister Proctor was also a gifted storyteller. His eldest daughter, Hester, would recall, “To his friends, he was an endless source of tales and anecdotes, tall and otherwise. His early adventures and escapes were many and exciting and they cost nothing in the telling.”[1]

Growing up in Colorado during the frontier period had a lasting impact on Proctor. Like many young men during this time, he intensely explored the wilderness and took great pleasure in the pursuit of hunting. Reflecting on these experiences in Denver, he would pen in his autobiography, “It colored my life and influenced me greatly.”[2]

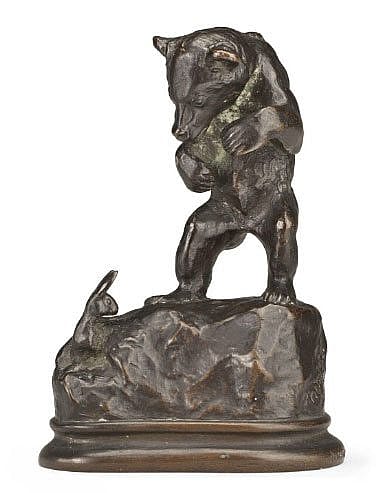

Throughout his busy life as a sculptor, Proctor continued to make times for hunting excursions. He also delighted in retelling his adventures, which often included his own weaknesses and misfortunes. His role as hunter was a large part of his self-image. In fact, whenever the artist was interviewed or asked to speak about himself in public, he often began and ended his message with stories, invariably ones that reflected his prowess with a rifle and his adventure on the hunt.[3] Inevitably, his hunting escapades found their way into his sculptures, ultimately strengthening his power of observation and association with wildlife. His wonderful sense of humor also permeated his works, particularly his smaller, more intimate pieces such as Bear Cub and Rabbit. Here Proctor exhibits a fearful, yet playful spirit between two of nature’s familiar inhabitants, capturing them in a moment of surprise and wonder. One can only guess, with a grin, the next move. A contemporary of Proctor, Charles M. Russell, also used humor in many of his sculptures depicting wildlife. In Mountain Mother, Russell focused on the family unit and juxtaposed the playful nature of the cubs with the watchful, protective instinct of the sow. In both cases, the works reveal a tender, good-humored side of the artist. In making their animal sculptures, Proctor and Russell drew on personal experiences, stories, and observations.

Toward the end of his career, in response to urgings by his family, Proctor began writing about his adventurous life. In addition to passages about his childhood and life events, which were later compiled into his autobiography, Sculptor in Buckskin, he also wrote an array of short stories. These stories add a remarkable dimension to his life and our understanding and insight of him as a sculptor. To our knowledge, the short stories have never been published and, therefore, further attest to the richness and depth of the Proctor archives, which include historic family and career photographs, unpublished chapters to his autobiography, correspondence, and newspaper clippings related to his works. The artist’s family, through the A. Phimister Proctor Museum in Poulsbo, Washington, recently donated his extensive archives to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. It is with great pleasure that we present one sample from his writings.

Mrs. Bruin and Cubs

By A. Phimister Proctor

“Woof! Woof!” growled Mrs. Bear.

I took aim with my rifle and was just touching the trigger when a wee cub rushed to its mother’s side from the bushes. I lowered my rifle. I didn’t want to shoot the mamma of such a young cub.

“Woof!” Mother said again.

Another little chap came out from hiding.

“Woof!” again said the mother.

Nothing happened. Mrs. Bear was standing on her hind legs, looking anxiously in every direction. Then, with her nose, she tested the breeze for scent. Nothing doing. The breeze was coming from her to me. She dropped on all fours.

“Woof! Woof! Woof!” The last warning was louder and sterner. It brought out No. 3 cub. He was sleepy and sulky. He didn’t want to come.

Mother scolded him. For some reason Mrs. Cuffy become more alarmed. She had heard me coming down the mountain on horseback, but couldn’t see me. Hastily she grabbed little No. 1. She pushed her to a tree and made her climb up. Then, hastily, Mamma hustled No. 2 up the tree. He didn’t want to go. As she pushed him up, No. 1 slid down. She boxed her ears and sent her back whining. Then they both tried to come down. Mamma spanked them both and made them squeal. Mother dashed for No. 3. He skipped off into the brush, she after him.

She turned. The first two were slipping down. In a moment she was spanking them up. She again got after No. 3. He tore around through bushes. she caught him and cuffed his ears. He hadn’t heard any noise. There wasn’t any danger. Why was Mummy so worried?

She had to drop him again and rush at 1 and 2. Back up they clawed, squealing peevishly. No. 3 was a pest. Mother was getting cross. She spanked him so hard, he squalled. Just as she got him to the tree, No. 2 dropped.

Then Mother got angry. She spanked them so hard they were all squealing. No. 3 was sassing her. What he got sent hi up the tree way out of reach of Mummy’s paws.

Then, standing on her hind legs, the old she looked about. Nothing in sight. She gave some orders to the babies (I couldn’t understand them), then she galloped up the mountain.

I think she told them to stay up the tree where they were safe.

In a few moments they started to slip down out of the tree, the wee’st baby of them was last. She slipped and fell eight feet and landed with a squawk. She lit out after the others, crying and whining for mamma.

Notes:

Notes:

1. Alexander Phimister Proctor, edited and forward by Hester Elizabeth Proctor, introduction by Vivian A. Paladin. Sculptor in Buckskin (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971).

2. Ibid., 202.

3. Peter Hassrick. Wildlife and Western Heroes: Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor (Fort Worth, Texas: Amon Carter Museum in association with Third Millennium Publishing, London, 2003), 102

Post 139

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.